Читать книгу Ginger and Ganesh - Nani Power - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеKrishna and Curry Leaves

Miracles abound

IT IS SUMMER of 2008. I am driving towards my first cooking class, a bag of vegetables beside me, as given to me on a list in the email.

I am tired. I just got back from vacation with my kids and my then-boyfriend. We had been together for two years and had become engaged. But the vacation seemed to break open the deep incongruities in our relationship, and the fissures widened. We fought and didn’t talk. We came back and it was all over.

On some level, I have to examine the fact that I felt I needed this relationship—that he had two boys like myself, and that I needed to remarry and have a stable home environment. But did I really love him, did he inspire me, was he someone I loved to talk to at the end of the day? Not really. We actually had nothing in common.

But then one starts to think: I have lived the family life with child rearing. What am I seeking exactly? I started to consider something more. I spent hours debating this with friends. It was an open dialogue, one that was not meant to be solved as much as discussed, endlessly. Soul mate vs. simple companion vs. friend with benefits vs. sugar daddy vs. best buddy—we jumped around with so many theories and ideas, if we were seeking the cure for cancer we probably already would have the Nobel in our hands. But of course, with all this talk, we had nothing and knew nothing. Just a liberal bunch of women dancing salsa or zydeco, going to farmers’ markets, attending yoga ashrams, drinking pinot grigio and trying out Buddhism. Dating here and there, with not much enthusiasm.

But I did know one thing. I wanted to learn Indian food. I didn’t think these two things, however, had much to do with each other. I was wrong.

MY FIRST TEACHER said she was from Gujarat, the most northwestern state in India. A quick bit of Googling and I discovered that the people are known for their sharp business sense. In fact, out of Forbes’s list of the ten richest men in India, four of them are Gujarati. Gandhi was also “guju,” as slang would put it. They also house the most vegetarians in all of India, and as every Indian will tell me in the days to come:

Now Gujarati, they know how to make veggy food.

I drive in this late summer day, to meet my first Indian cook, Mishti from Gujarat.

Mishti lives in one of those apartment complexes, newly built, near the area of Virginia known as Herndon. After meandering around the parking lots, which all feed into each other and make no logical sense, I finally find their ground floor garden apartment. I don’t know Mishti: I don’t know if she is old, young, how educated; at this point, I don’t even know where she is from—it is a blank slate.

So I find her door, another portal of mystery. A tiny dried wreath of flowers rests on its knocker.

And there she is, my newest guide to this soft world. Perhaps this is the bittersweet feeling a man feels when he pays for a prostitute, that this is something ideally you would have in your life naturally, and you are paying for such a private rite, and there is probably such a sense of vulnerability that you would need another human being, and yet a bit of pride that you did, after all, strike out and seek it.

And, yes, it is a need for a form of mothering.

My newly adopted mother, in this moment, is tiny and young, in her late twenties. Someone in the know told me Guju-babes are known for being sexy, that they tend to stay in shape. And such authority she possesses so young. She is elfin, gracious, and I leave my shoes by the door, which I always do in the Indian houses, and now I’ve come to think of it not just for cleanliness, but also as some meaningful ritual: as in, who you walk as in this world shall be left behind.

I have brought my son, not wanting to leave him at home. She gives him water and special sweets she brought from India, a golden hair-like candy that is delicate and saffrony, and crunchy hot biscuits. The apartment is simple, sparse, dotted with a few candles, and small icons of individuality, an altar to Ganesh in one corner, with a tiny brass frame of a family, blurry—I am unable to see more than the dim figures of a man, woman, a few kids of varying ages, amidst the dust of incense lying snaked on the table. The kitchen is merely a corner of the room, harshly lit by fluorescent. In the American need for convenience, have we achieved more time? No, not likely. Are we enjoying our meals? No, I don’t think so. We are stripping ourselves of a basic sensuality that our bodies crave, touching our food, loving it before we sacrifice it. And we are longing to change this: food is hot right now. Classes are filling up, the TV networks are packed with shows teaching us how to go back to the basics.

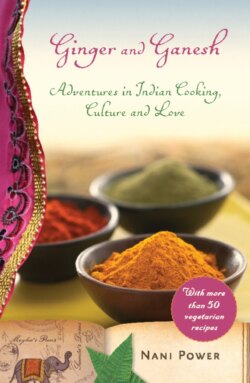

A brief aside about Ganesh: how I am growing to adore him. Something about the Indian deity touches me, and I collect his figurines in my house. I love the fables about this elephant-faced, potbellied God. Most Indian homes will have a small Ganesh sculpture somewhere. He is heavily revered. He is supposed to be the first deity one worships in Hindu ceremonies called pujas (offerings), especially at the beginning of any venture, especially any creative venture, so perhaps that is why I have a fondness for him. He is considered the problem solver, and I’ve heard you can offer him a cracked coconut in particularly trying times. But it is a certain joviality and warmth that he seems to exude that I really love.

I am here to learn the basics. We wash vegetables and she is shy, diligent in her kindness. And she tells me of her home. She adds twice the amount of sliced green chilies to every dish, and tops it all with a spoon of sugar, a Gujarati trademark, she says.

We start with a spectacular dish called Saam Savera, or “morning evening.” I had asked Indian friends about it when she emailed it to me, but nobody had heard of such a poetic dish. Small balls of mashed potato, seasoned with coriander powder, cilantro, and chopped green chili enclosed in a pocket of spinach, rolled in corn flour, deep fried, sliced in half and presented in a rich tomato based gravy. The whole dish is surreally beautiful, the black line on the edges, the green, the white, and the red, and I believe it is meant to conjure the look of the moon in the morning. It tastes so delicious. In addition, we learn how to make our own homemade Indian cheese, paneer. Quite simply, it is milk heated and curdled with lemon and then squeezed until it forms a solid block. This simple cheese is the basis for many Indian dishes.

Her husband, hair freshly washed, smiles up at me in a flash, as he sits on the carpet on his computer. Is there anything more beautiful than the look of wet, black hair? I’ve always been charmed by it. A soft peacefulness floats in this apartment, a sweet hammocky feeling of calm. They have no artwork, no fancy TVs. They are basic people and decorate with small symbols of their shared life: a magnet from Jamaica, a framed caricature of them both from another beach vacation, and small odds and ends which create the quilt of their lives. I can’t help but see them and soak them in. I’m a spy of sorts.

Later, while sampling these lovely treats we have prepared, I ask her personal questions, as I tend to butt in whenever possible.

We have been married a year, she says when I ask.

My wife looks so young, doesn’t she, says her husband, with pride and amusement; I look like an old man next to her.

But they are the same age and look it. I suppose he is telling me, Inside I feel so old. But I don’t know why he would feel this way. I see him as one of the many bright stars from India, shiny-eyed, working in the tech world in new Virginia, a man whose old culture is only a whisper.

He leaves through the sliding glass door into the parking lot. His BMW is parked outside, glimmering even under the shade of the trees. The license plate says MIRACL BOY. Oh, I ask, impertinently, why is he a miracle boy?

She laughs a laugh that comes like muffled bells, and a tinge of reticence bathes it, Oh, because he is a miracle boy, she said, and I laugh, too, and I leave it at that, there is something so softly said, which is, You are not there yet. I perceive this subtlety and let it go.

And then I get to thinking: How we all do this dance. This stepping forward and pulling back, the hurting and loving we do our whole lives. And how I’ve come into her house, I’ve essentially invaded, I’m learning her family recipes, I’m cooking them, I’m eating them, I’m writing about them even, and even worse, I will enter and know more and more until I will know as much as I can. They will stand raw and naked, eyes bright, smiling. And they are freely giving.

And it just kills me. And then, I suppose we will love. And then, I can stay or just go away. And we deal with this all the time, don’t we, this approaching, retreating, and think not much of it. But it seems to me so essential to us and who we are. I realize that I, too, must give, not just the twenty dollars that I give her at the end. This can’t be a prostitution of culture, of food. It is given with her eyes looking into mine. I have to give myself as well.

I think about this during the week: I have to give.

I LAUGH WITH her during those two hours, and write all the details. And make plans for the next week. Her cooking is delightful and again, so different from my first teacher, Stella. Crested with her own style and tastes. She adds, as I’ve told you, a bit of sugar to everything, twice as many chilies it seems, and always a jarring dose of lemon juice. At first, I’m not used to these flavors in Indian cooking but as time goes by, I find I add them myself as well.

As the weeks go by, I have leaned a chockload of treats from her—a deliciously savory version of Mattar Paneer, the famous peas and cheese curry of Northern India—but without cream, simply bathed in an extremely spice-laden rich tomato-based gravy. A sumptuous stuffed okra dish with coconut. Malai Koftas, rich potato dumplings in a creamy soaked gravy. And one day, she produces Indian jewelry for me to see, and I buy a wedding set of extravagant turquoise jewelry. But it is a special day when we feast on a delicious assortment of chapathis that I have learned not so expertly to roll. She had pulled out the important skinny Indian rolling pin to create the ever-popular Aloo Paratha, a flatbread filled with a savory potato stuffing, a staple item in any Northern Indian home, and a spicy paratha stuffed with shredded carrots, and for variety, a green chili paneer variety. We are tearing off large chunks and dipping them in curd and mint chutney. My lips are burning and I am having a serotonin high induced by all the green chilies.

Her husband, as usual freshly showered, comes padding on, usually to check the laptop on the sofa and then go wash his car.

There is a festival this weekend, if perhaps you would like to go, he says.

Yes, says Mishti, an Indian one.

Oh?

It is at our Krishna temple. You should come. There will be lots of foods and things.

I would like to understand more, so I ask her about this worship of Krishna, which is perceived as a cult in this country, merging with Hare Krishna. But I learn that they are followers of Vaishnavism, a devotion to Vishnu (God) as personified by Krishna. Who is Krishna? The eighth avatar, or incarnation of Vishnu, who is the all Supreme Being. Some say he is a Christ figure. As a young boy Krishna is the foster child of cowherds and shows his divine nature by conquering demons. As a youth he is the lover of the gopis (milkmaids), playing his flute and dancing with them by moonlight. The play of Krishna and the gopis is regarded in Hinduism as an image of the soul’s relationship with God. The love of Krishna and Radha, his favorite gopi, is celebrated in a great genre of Sanskrit and Bengali love poetry. You will recognize him, if you ever look at devotional Hindu art, as the beautiful man with blue skin (Krishna means “black” in Sanskrit), with golden clothes and peacock plumes in his hat. And there is his most famous moment: with his friend, the great warrior Arjuna, about to go to battle. Arjuna turned to him and asked, Why should I fight? Where am I going after life? Whereupon, Krishna turned and thus spoke the famous scriptures: the Bhagavad Gita.

That night, I read about Krishna and Vaishnavism. I read the great principles, of which the first three are:

1. An absolute reality exists.

2. True success in life comes only by understanding reality and our place within it.

3. Science gives a limited picture of reality; abundant evidence suggests that part of reality exists beyond the reach of our senses and scientific instruments.

AND SO, I know learning to cook is a humble way to approach the whole idea of reality. There are transformational, alchemical natures to the act that imply spiritual initiations. A potato, given care, becomes much more than a potato. It becomes something sublime. It feeds us as we grow. Cooking, eating are the threads of our communal and family life.

The next week, Mishti and I are making potato and tomato curry. The smell of curry patta (fresh curry leaves) fills the air, an indescribable scent and flavor. This ingredient confuses Western cooks. Is that where curry powder comes from? No, curry powder is an English invention, and probably comes form the Tamil word for stew, kari. Curry leaves are from a small plant, the Sweet Neem, and have a smoky flavor and scent, almost mushroomy. And, of course, they are quite medicinal in Ayurveda, which is the traditional, native medicine of India that utilizes natural plants and herbs. Good for digestion and diabetes. The scent however has no words for description, but has a lovely warmth.

The usual car washing is happening in the parking lot. As we sit down to wait for the stew to cook, Mishti pulls out a large book.

What is this?

Our wedding pictures, she says.

I have not dared to ask if it is a love marriage or arranged, but whatever it is, it is working. One can feel the love between these two.

I have noticed their pictures do not festoon the wall like most couples.

Oh, she says in her perky voice, I keep meaning to put them up.

A yellow vinyl album is produced, with an airbrushed flower on the cover.

It is simple, and plain. Not like the large white silk and pearlized albums Americans would have. It is simple, until you open it up!

And then, she and her husband become the loveliest prince and princess one could ever imagine. I am quite honestly in awe, in the way one would be looking at the pictures of royalty from a fairy tale. She is covered in jewels, colors, and henna spirals in patterns on her hands. He is in a stoned turban, proud. Both are beautiful and golden. And then there is page after page of celebrations using old methods—the rubbing of turmeric, the women bringing terracotta pots of water to the party, the festive kaleidoscope of colors, platters of endless dishes and sweets. I find myself not quite jealous, too strong of a word. Colorless, lacking in spirit. As if I am Cinderella looking at the stepsisters’ finery. I have been divorced for five years now. I have lost in some sense, my grounding as a woman. And did I ever have it? I am a victim and a beneficiary of my culture. I stand in such freedom, to go where I like, to be whom I like, to see anyone I wish. And yet, I feel uncared for, unloved. I feel I am not part of an endless web of relations, like these ones I see in jewels before me. I did not have a family decide my spouse, and perhaps, it would have been better. We are more free and yet, we are just lost in space, it seems.

I’m reaching out to be in the presence of connectedness as well, through the vehicle of food.

I see her family; her mother looks like a beautiful mature version of herself. And I see the groom, not in family shots. I see him standing ceremoniously in front of a framed picture. It is, it seems, the same picture I see in their altar with Ganesh and the incense. And where is his family? I ask, with innocence.

She smiles warmly and her eyes glisten.

Oh, she pauses. But she doesn’t hesitate or leave me out. She tells me with all her heart.

They are passed away. They died in the earthquake of 2001.

Oh my God. I am so sorry. All of them?

Yes, all of them. The entire family. Except for Duli.

I look at her and back to the picture next to the frame.

Yes, he was there in the rubble. For five days.

There is a silence, not awkward, just appropriate.

The dal we are making has signaled it is ready for the next step with three insistent whistles from the pressure cooker. Life always intervenes.

I just say, I am so sorry and try to comprehend such a thing, but I can’t.

And she told me with such openness, as if their story was now allowed to pass to me, as I had become a person to them. I felt honored.

As we added the tadka, which is the last finishing touch of spices to the dal, Mishti’s husband Duli drives up to the parking space in front of the sliding glass door, his BMW newly washed and gleaming, the license plate clean and white: MIRACL BOY.

THE NEXT WEEKS pass by quickly as we sizzle and fry such delicacies. Mishti’s spiciness has now suited my palate, and I welcome it. We move onto such wondrous dishes as Khadi, a very popular quick and easy yogurt sauce enjoyed in many Indian homes, flavored with a typical spice mixture, served with breads or rice. I realize this sauce is no doubt the origin of the “curry,” doctored and hideously malshaped, we knew back in the ’70s, brought over by English colonists. It is the creamed casserole party dish, with copious amounts of dusty lemon-colored curry powder and the little side dishes of raisins and peanuts. My grandmother made it, bathed in cream. And I learn chole, the chickpea curry, savory and spicy, a must for the everyday vegetarian, served with raised yeast bhature breads. I am taught to roll these with the lightest pressure, like the breath of a baby, very fast but very soft.

And then, one day I walk in to see a pile of odd boxes, from liquor stores.

Oh, are you moving, Mishti?

Yes, she says gleefully. We are going to Connecticut for relocation.

And then, by the end of the month, they are gone.

THE GANESH STATUE is always accompanied by a tiny mouse. Upon further investigation, I learn that the mouse symbolizes a minute vehicle for a cryptic subject. Because these small animals live in darkness, under the ground, it reminds us to always keep looking around, sniffing out knowledge, to illuminate ourselves with the inner light of wisdom.

I keep thinking about Duli. I really wanted to ask him something. One day, after they had found out I was a writer, Mishti called him from washing his BMW. She pattered on in Gujarati and he came running in. This was early on.

So you are a writer! he said.

Yes.

I love, you know, to go to Borders. Sit around reading. I’d like to write something one day. I have actually, he said, a good story in mind.

Now keep in mind everyone says this to writers, all the time, constantly.

Really? Well, why don’t you write it?

Ohh, he laughed. No. I cannot.

We left it at that.

But I wanted to ask Duli later, after the wedding album moment, Tell me everything. How did you do it? How did you survive for five days? Did you have water? Did you hear your family? How did you sleep?

There are so many questions. I want to hug him, and say, God, man!

Only I can’t. I just smile and say, Hi, as I stir okra curry.

He seems a different person now. In my eyes, he now possesses the distinction of tasting death, which I haven’t. I truly believe if you have had this happen, you are different from others. Was I ever lying under the rubble of a building for five days? A writer is a very curious being. A human being has to, however, respect peace and be kind. So I often balance them, failing a lot of times, but in this case, I just don’t feel I am quite there yet to ask and receive such knowledge. Now when I drive by their complex, missing those sessions cooking Gujarati food, I wonder on that. Mysteries are mysteries, I tell myself. Being mystery is enough, isn’t it?

MISHTI LEAVES FOR Connecticut. They start a new life, with a few boxes. I miss them.