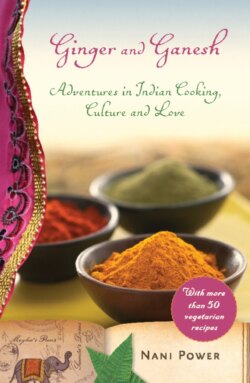

Читать книгу Ginger and Ganesh - Nani Power - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеVishnu of Suburbia

The teeming bazaar of the market is now a cold, plastic Costco. But you can still buy basmati rice in a burlap sack

SO, OFF TO the suburbs in search of real Indian food and per-a haps more (adventures!), I drive into the gleaming developments, with their spraying fake lakes, the hot sun beaming on the sticky asphalt. Houses neatly packed in streets with cleverly wrought names—Mooncourt, Fieldstream—as somehow poetic tidbits meant to evoke a new world.

It is a new world.

Technology companies line Route 50 and the surrounding areas. BMWs shine in the parking lots, lovingly washed by their owners, and, looking around one would think they had strayed into some expensive gated community in India. Everyone is Indian. They wear the popular sporty clothes of Nike and Adidas, they drive American gas-guzzlers, and they fill their carts at Costco with Go-Gurts and frozen Mystic pizzas like any American soccer mom.

But when I enter the homes, my shoes left at the door, it is as if stepping back through the centuries. Gone is the flash of modern American culture. Breads are made by hand, quickly squeezed and rolled on round wooden blocks, and seared on old cast iron tawas (flat griddles). And the spices they use have been used for thousands of years, each with medicinal purposes, each lending a subtle note to the finished dish.

These methods have survived in a world spinning as fast as we can stand, hurtling us forward into ever-fresher horizons. And yet, behind the doors the ancient world still exists: women passing on their treasured dishes to each other. No, you roll like this. Here, try like this one. Our throats slightly choking as hot chili oils fill the air. The delicate and mysterious paste of sweets brought over on the plane from Gujarat, most generously offered. It’s an ancient bonding and one I seem to need, the feminine tradition of hearth-tending. Why have we fallen away from it in our rush to succeed in the world? Why is cooking a lovingly prepared meal from natural ingredients, from “scratch” as we like to say, gone to the wayside? And, as a vegetarian, flexitarian, or even plain meat-eater, who wouldn’t want to learn the vast bevy of vegetable dishes that Indians delight in?

There is another element at play in this journey: my newfound vegetarianism comes from a place where I am trying to experience ahimsa, the Hindu and Buddhist concept of “do no harm.” Of course, this applies to what we consume; essentially, animals that have experienced harm and violence arrive on our dinner plates. But I am also exploring the idea that energy, positive or negative, can permeate our food. We talk of food “cooked with love” as if it palpably makes a difference to our taste buds, and I think it does. Surely the energetic state of food preparation—either in a cold, sterile factory or the hands of a loving person—contributes to the blandness or the goodness and delectability of food. I have to believe this is so, even for those who would mock such new age thinking. Therefore, it seems to me that when we are taught cooking, person to person, we are engaged in the highest method of teaching, a shared respect and kindness, a cultural exchange and a lasting warmth that just reading a recipe cannot impart. Well, you may say, isn’t that what you are producing here, just another book? Yes, but I am hoping that these recipes feel as authentic and true as when they emerge from the hands and mouths of these ladies, and that you too will feel the love and kindness that was imparted. These weren’t produced in test kitchens: they were shared like old stories, lovingly described and respected. And I am hoping that this will encourage you to reach out to your neighbors, be they from Pakistan or Romania or Appalachia or Long Island, and ask them: What are your family recipes? Can you teach me?

I notice a stark difference culturally in kitchens between Indian and American concepts: Americans have transformed their cooking spaces, or at least they long to, into casual centers of social entertaining—islands with stools for lounging on with chardonnay as the host chops a few shallots. Americans have great grills for flaming this and that. Even a sitting area bleeding into the area for more social activity. And, if you can afford state of the art technology for the best culinary experience, customized sub zero refrigerators. There are Aga stoves that keep temperature perfect for instant baking, pizza ovens, wine coolers, etc. And yet, in these kitchens, most do not cook. Bring them a chicken and they will look at it warily. Show them a pile of okra and they will not know what to do. Cooking has come to mean an entirely different thing: there is so much convenient food, cooking has been stripped of its sensuality. We do not need to touch food to make a meal. We are opening packages. Salad and vegetables are packaged, as well as meat. We tear these open, slide them on a plate. Dinner is done without a hand actually touching it.

The Indian kitchen is simple, a factory with a few well-worn tools: cutting board, knife, pressure cooker, chapathi roller, tawa, and blender. Besides a few pans and such, that is it. Oh, and a precious spice tin that they all seem to have: a cylindrical container with six spice bowls and a small spoon, kept by the stove, called a masala dabba.

AND SO, ON my strange modern journey of female apprenticeship, I drive through the plasticized furrows of Virginia, venturing into a smooth and expressionless development to augur the elements of an ancient rite: cooking and talking with women who will teach me the methods of a home. In a sense it is like sitting in the darkness of a cool movie theater, awaiting the feature. I am expectant and happy. There is a great sense of trust already flowing through the air, because first of all, the domestic location has eased everyone’s minds. It feels safe and comfy. And next, there is a certain respect being shared and honored, that I, coming from such a modern country, would care to know these things. Most of the people who responded to my ad seemed genuinely surprised that I cared to know about their food. But where else would I learn? From a cold book procured at Borders, flopping on my table, as I try to measure the ingredients? How would this teach me anything? I was craving continuity, connection. A femaleness. This is how we do it. And it’s complicated, Indian food. There are many spices and herbs, added at specific times. Of course, I would come to realize that everyone, naturally, had their own ways and methods, and that in navigating this journey I would find my own way. Which is a microcosm of life anyway.

MY FIRST HOUSE, a woman named Mishti. I am almost there . . .

I start to wonder, with a small nudging of pain: I’m looking for cooking lessons. Or am I? Am I looking for a mother? a friend? or an artificial lever into another’s culture? These thoughts pervade as I careen through the trimmed suburbs. I wish to learn but not intrude. I try and keep that in mind.

Meanwhile, I am lost in a maze of beige houses made of siding and fake rock. I turn around and start again. They all look the same.

I look at my address again. Yes, back the other way.

I turn around.

I have come to my first house, first cooking lesson and I am walking up to the door.

My first encounter—the sharp, bracing tang of ginger.

LIKE I SAID, here I am: in my forties, divorced, with two kids. I live in Virginia solely for the sake of my kids. My family is nearby and very present in our lives. It is exurbia, rural countryside of horse farms bleeding into the new sterile suburbs. There are certain reasons that I prefer this to a homey old cabin on a farm: upkeep. I can’t deal with furnaces and leaky windows, lawns to trim and hedges to clip. I come and go and write, and that is all I can do. I can also cook. But I fit in very few categories. I am not the barbecuing, SUV-driving suburban mom surrounding me. I am single, and therefore on some level cast out of this group. I don’t merge with the immigrant families, such as my Indian neighbors: they keep to themselves. Am I searching for a husband? No. I am happy to live my own life. Am I searching for love? Of course. But what am I not searching for? I am always essentially in the mode of searching. On any given day I could choose to eat from twenty-two different regional foods, from Vietnamese to Ethiopian. I can date men from the local country fields or go to Washington DC and dance with politicians, or meet an Egyptian waiter or a Russian mathematician. I can go online and meet Turkish men or African or Arab. I could go live in Nepal or move to New York City. I have too many choices. I am too free on some levels. So I come back to basics. Love. Friendship. Cooking.

This act of searching led me to Craigslist, to a community of ladies, of all ages, all classes, from various regions spanning the great continent of India all nestled in the suburbs, who were willing to teach me the vegetarian foods of their great country.

And then, via Craigslist, I also fell in love. Searching isn’t a bad thing. Sometimes you can find what you are searching for.