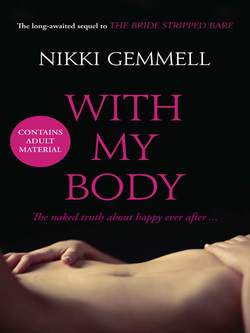

Читать книгу With My Body - Nikki Gemmell - Страница 13

Lesson 8

ОглавлениеMarriage: to resign one’s self totally and contentedly into the hands of another; to have no longer any need of asserting one’s rights or one’s personality

You were born in mountain country, north of Sydney, a place assaulted by light. High hill country with ground leached pale by the sun and tap water the colour of tea and you always looked down when walking through tall grass, because of snakes, and at dusk the hills glowed pink with the force of the sun, trapping the heat under your skin, in the very marrow of your spine; that could not be gouged out. Whispering you back. Home. To a tall sun, a light-filled life.

When you were eighteen you climbed down from your high mountain place. Went to university and became a lawyer, in Sydney, the Big Smoke. Winged your way to London in your mid twenties: restless, fuelled by curiosity, eager to gulp life. After several years of hard work there was the expat’s dilemma of wanting to return to Australia but unable to decide when; of meeting Hugh – the man who did not excite you but sheltered you; of one thing leading to another and now you are in this rain-soaked island for life, staring at a mountain of washing by your bed and dreaming of the roaring light. After the second bouncy boy the decision was mutual: a move to the west country, the Cotswolds, for space and fresh air, a better life. Your dream of a partnership in the law firm fell away under the demands of motherhood; after the first maternity leave you never went back, lost your professional confidence and now your children cram every corner of your life. You are driven by perfection and ambition as a mother, just as you were driven as a lawyer. Everything you do you dive into completely, attacking with a ferocious will to succeed and hating it when you fall short. Which you do now, often, to your distress.

Hugh has said it’s good you’re Australian in this place; your accent can’t be placed, you can slip effortlessly from lower class to upper, can’t be pinned down. You know it’s good Hugh is not Australian for he can’t nail the broad flatness of tone that any Aussie East Coaster would recognise as originally from the sticks. The bush has never been completely erased from your voice; wilfully some remnant clings to it. Your vowels have been softened by Sydney, yes, but they still carry, faintly, the red-neck boondocks in their cadence. England hasn’t left a trace.

You will always be an outsider here. You revel in not-belonging, enjoy the high vantage point. Marvel, still, at the strict sense of place, of class they cannot breach – the fishing and shooting, the villas in France, the stone walls that collect the cold and the damp, the wellies even in July, the jumpers in August, the hanging sky like the water-bowed ceiling of an old house. How can it hold so much rain, cry so much? Days and days and days of it and at times you just want to raise your arms and push up the clouds, run. Hugh will never move to Australia, he has a blinkered idea of it as the end of the earth and deeply uninteresting, really – that the only culture you’ll find there is in a yoghurt pot.

You can see your whole future stretching ahead of you now until your body is slipped into this damp black earth, the years and years of sameness ahead. Once, long ago, you never wanted to be able to do that, curiosity was your fuel, the unknown. You carry your despair in you like an infection that cannot be shaken.

But now. A dangerous will inside you to crash catastrophe into your life, somehow, God knows how – or with whom. It’s been brewing for years; it’s something about reaching your forties and seeing all that stretches ahead. You’ve never been fully unlocked with Hugh and bear responsibility for that, entirely.

For always wearing a mask. For not being entirely honest. For never showing him your real self.