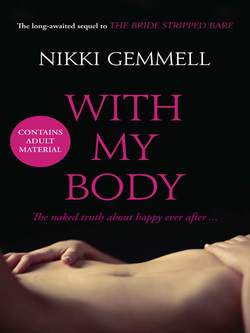

Читать книгу With My Body - Nikki Gemmell - Страница 18

Lesson 13

ОглавлениеFriendship – a bond, not of nature but of choice, it should be maintained, calm, free, and clear, having neither rights nor jealousies, at once the firmest and most independent of all human ties

Your hand is straying into your pants, thinking of other things entirely, school dads, their spark. How one in particular, Ari, would spring you alive, back to the woman you once were. Ari, yes, he’d have the knowledge, the instinct; but you’d never do it. God no, the mess of it. Susan is still in your ear, telling you that Basti is just about to pass his first flute exam, can pick up any piece of music and just play it, he amazes her. (Rexi, God love him, is on page six of his guitar book and unlikely to progress.) And the coffee morning, ‘Can you run it, babes?’ Of course, yes. Susan will bake some muffins for you: ‘I know you’re not good at that bit.’

She is constantly baking, her house a show place, her children spotless – yours are the ones who sometimes wear grubby t-shirts you’ve flipped inside out, have cereal for dinner and Coca-Cola as a treat. In Susan’s kitchen is a huge notice board in an ornate frame crammed with certificates of achievement and baby photos and colourful kids’ drawings. The occasional certificates your own children get are lost in piles, somewhere, along with school reports and photos and Santa lists and they will all be sorted, sometime. Long ago, you were in control of your career, your friends, your life; you never feel in control within motherhood. The guilt at so much.

The time you folded up the push chair and placed it in the boot, only to hear a squeak – baby Pip still in it.

The time Jack rolled off the bed as you were changing his nappy and ended up with a dint in his skull.

The birthday cakes from Tesco, year after year.

The computer games that keep them all riveted, baby included.

The occasional McDonald’s, three quarters of an hour’s drive away on a Sunday night.

Basti, of course, has never had it in his life. He tells you this when he comes to your house. He has inherited his mother’s heightened sense of censorious rightness, about everything in his life, and you fear for what’s ahead of him, how the wider world will chip away at that. Meanwhile Susan bustles about in her flurry of energy, a tiny, dark sparrow of efficiency with an enormous, puffed chest, making you feel deficient in response, that you’re always running and never quite catching up. Have had no role model in life for this. The best mothers are those who had bad mothers, you think, because they know what not to do – but what if you never had a mother? If she died before she was lodged in memory.

Susan’s voice veers you back.

‘Wasn’t that homework hard today? Basti got it, eventually.’

‘Rexi took a while. I had to snap off the TV just to get him to the table …’

‘We don’t miss ours. The kids never ask for it.’

A pause. ‘Lucky you.’

Television, of course, is babysitting for you, your guilty secret. And you didn’t notice exactly what Rexi was doing in his maths book.

‘Just checking you’re still on for Basti this Thursday?’

You’re always scrupulously generous with play dates; it’s why the routine works.

‘Of course … can’t wait.’

‘Did you get the notice about nits? I know you never check their schoolbags, just reminding you. Basti’s never had them. I don’t know who it is …’

You shut your eyes, your knuckles little snow-capped mountains around the phone. Because of bath time, several hours earlier – all the boys, even Pip – and dragging out the lice with all their tiny, frantic legs. And Jack has a pathological aversion to nits, almost vomits with the horror of them, yells like you’re scalping him. Then the pleas, the threats, to finish the homework due tomorrow, to stop the Wii, get to bed. Rexi storming off in frustration, his arms over his head. You feel, sometimes, he’s a great open wound that you’re pouring your love and puzzlement into. What’s going on in there? Does it ever even out? He’s only nine. His teacher says it’s something to do with boys about this age, from seven onwards, their teeth coming through; there’s a huge psychological change in them, hormones swirling. Does he mellow with age, does he strengthen? Is he too much like you, too emotional? You are fascinated and fearful at the depth of his feelings.

You are not responsible for your child’s happiness, Rexi’s teacher in her fifties told you gently the other day.

‘All you’re responsible for is what is said and done to them, as a parent. That’s all. Nothing else.’ You must remember that.