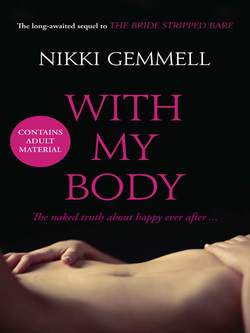

Читать книгу With My Body - Nikki Gemmell - Страница 8

Lesson 3

ОглавлениеShe is forever pursued by a host of vague adjectives,

‘proper’, ‘correct’, ‘genteel’, which hunt her to death like a pack of rabid hounds

Your children are just back from school. Outside is icy-white but it is frost, not snow, a brittle blanket of stillness that clamps down the world. The frost has not melted in the mewly light of the previous few days. The kids champ at the bit inside, they want to be out in the light, before it is gone; almost. You let them loose. They spill through the kitchen door, run. Storming into the crisp quiet, roaring it up; bullying the frost, its deathly stillness.

You smile as you stare through the window at your boys – so much life in them. Such shining, demanding, insistent personalities, all so different. You make another cup of tea, the last of the day or you won’t sleep; green tea because so many dear friends are getting ill now – three at the moment, with breast cancer. And with your mother’s history you have to be careful of that.

You’re so tired, you have four boys if you count the one you’re married to and the exhaustion is now like an alien that’s nestled inside your body, sucking away all your energy. It’s an exhaustion that stretches over years, since your first child, Rexi, was born; the exhaustion of never being in control anymore, of never completely calling the shots. Once, long ago, as a single career woman, you did. You dwelled within a white balloon of loveliness, in the city, loved your beautifully pressed, colour-ordered clothes and regular weekend sleep-ins, your overseas trips and crammed social life.

But now this. A tight little world of Mummyland, symbolised by a mountain of unsorted clothes on the floor at the end of the bed. You can get the clothes into the washing machine. You can get them out. You can arrange them over the radiators to dry. You can collect the dried clothes and put them in a heap ready for sorting. But you cannot, cannot, get the clothes back into their cupboards and drawers. Until that pile at the end of the bed becomes a volcano of frustration and accusation and despair; ever growing, ever depleting you. Until sometimes, alone, you are weeping and you barely know why, your hands clawed frozen at your cheeks. ‘I can’t do it.’ Sometimes you even say it to your children, horribly it slips out – ‘It’s too hard, I can’t do this’ – bewildering them.

You weren’t this woman, once; despised this type of woman, once.

You are lonely yet desperate for alone; it’s so hard to get away from your beloved Tigger-boys, to steal moments of blissful alone from everyone dependent upon you. You feel infected with sourness, have lost the sunshine in your soul. You do not like who you have become; someone reduced.

Yet you are so fortunate, have so much. You know this, despairingly. Cannot complain but are locked in your demanding little world of giving, giving, giving to everyone else, all the time; trapped.