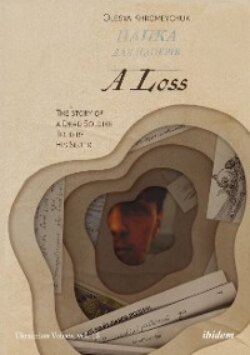

Читать книгу A Loss: The Story of a Dead Soldier Told by His Sister - Olesya Khromeychuk - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

A Facebook Message

ОглавлениеIf you have two siblings, and, after one of them dies, people ask you if you have any siblings, what do you answer? Do you say, “I have two brothers”? But that’s not true, because one of them is no longer around. “I had two brothers. Now I have one, because the other one is dead”? That is technically true, but it’s way too much information. People ask you questions about siblings to be polite; they don’t want to be traumatized by your family history.

It was a long time, during which I paused, looked confused and took deep breaths to fill the silence and calm my nerves, before I learned how to answer that question. “I am the youngest of three children.” That’s what I say now if anyone asks.

I am the youngest of three children. The eldest died in a war. Although one rarely dies in a war, one is killed in a war. When someone joins the army and goes to the front line, their potential death becomes a very real prospect. Yet there is nothing natural, nothing normal about death in a war. Someone who is fit to serve in the army is surely fit to live for many years to come. He or she is likely to be quite healthy, quite young, able to face challenges – the perfect ingredients for a long life. A sudden death should thus be the least likely end to such a person’s life. Yet it is one that should be expected in war. My brother ended up serving for almost two years and I spent almost two years trying not to think that the least natural end to his life was becoming more and more likely.

One day, I received a Facebook message from someone I didn’t know, saying “forgive my strange question, but we are looking for this person living in the UK”—followed by my mother’s name and details—“Don’t suppose she’s your relative?” As soon as I read it, I knew that one of those things I was supposed to expect but had tried not to think about had happened. I just wasn’t sure which exactly. A severe injury? Capture? For some reason, I didn’t really think of death. I looked up the person who had messaged me and saw that they worked at the Ukrainian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. I immediately thought that my brother must have been captured by the other side. I felt sick. Captivity seemed like the most frightening prospect to me. I had heard too many stories of the humiliation, torture and other horrors faced by the prisoners of war taken by the so-called separatists, and I knew how hard it was to free them.

It was a sunny Saturday morning, and I was on the underground in London, on my way to meet a friend in a park. As the train stopped at stations and the Wi-Fi connection reappeared, I got other similar messages: “Good day. I am from the military unit where your brother is serving.” Is serving! So, he must still be alive! I tried to calm myself. “Give me your number so I can get in touch with you.” I jumped out of the train and ran outside where there was phone reception. I phoned my mother realizing that I had bad news to tell her, but that I still wasn’t sure just how bad. I didn’t want to shock her so started by saying that “it might be nothing, although it sounds serious…” I kept thinking of captivity. In my mind I kept going through a list of friends I should contact to try and get more information, people who could advise us what to do to get him out. But my mum interrupted me and said: “I got a call from a commander. Our Volodya was killed on the front line.” She was so calm.

I felt a strange sense of relief: so, he hadn’t been captured after all! Almost immediately, the relief was replaced by an icy wave of reality.

In movies, when they show you someone getting bad news, the camera spins to help you imagine the person’s bewildered state of mind. It wasn’t like that. Nothing was spinning. I had a completely clear head: I told my mum that I was on my way to her place, checked the train timetable for the next train to her station, decided whom I needed to call and in what order. I messaged those people back on Facebook: “My mother has heard the news already. Thank you for getting in touch.” One of them replied: “We are just on our way to the morgue. Should be in Lviv tomorrow. The roads are bad here so the guys can’t drive quickly.”

I began to think how quickly I could get to Lviv. Could I be there before he arrived? The busy London train station seemed completely empty; I didn’t notice anyone. I texted my friend to tell her that I wasn’t going to the park.

It was only when I got on the train heading to my mother’s and phoned my father that I broke down. I had to say the words my mum had just said to me: “Our Volodya was killed on the front line.” I couldn’t do it calmly, like she had.

When I got to my mother’s place, we didn't really know what to say to each other at first. I didn't even know if I should hug her. We seemed to instantly reach an unspoken agreement that we had to get things planned for the imminent trip ahead of us. We had a task at hand that needed to be dealt with. Such moments leave little space for emotions. Maybe just as well.

Minutes before I had arrived, my brother’s commander had asked my mother over the phone if she wanted to see the photos of my brother’s body as it was found. She said she did. He sent them to her phone just as I entered her flat. The photos showed my brother lying on the black muddy ground. His head was bandaged with a white cloth. The red blood was seeping out on one side. Had they put the bandage on while he was still conscious? Did he feel any human presence as his life was trickling out together with his blood? Or was he completely alone when he died? Did he know he was dying? We had nobody to answer our questions. For the time being, we only had the photos. My mum and I looked at them together. First in silence and then wailing. Quietly. Then I booked our flights to Ukraine and went home to pack. My mother stayed at her place and packed as well. We agreed to meet at the airport the following morning. I was relieved that we were able to get to Lviv just before he would.

What followed was a week that seemed like a bad dream from which I couldn’t wake up. I never realized how shattering grief could be, and never thought that someone’s death could turn into a Kafkaesque bureaucratic nightmare. I realized how unprepared I was for the event I had been expecting at the back of my mind for nearly two years.