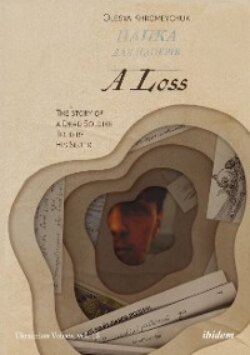

Читать книгу A Loss: The Story of a Dead Soldier Told by His Sister - Olesya Khromeychuk - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Funeral, Part I

ОглавлениеThe glass doors opened, and we were met with dozens of pairs of expectant eyes, all looking for a particular pair to emerge into the arrivals lounge. We expected to be met, so paused at the exit, staring at the people who mostly looked somewhere beyond us. My mum hadn’t been in this airport for years. She hadn’t seen its shiny new terminal, built for the Euro 2012 football championship. She looked so lost, like a child. I knew I had to take charge. I go back to my hometown regularly, whereas for my mother this was only her second visit in seventeen years. Her first visit was to attend her younger son’s wedding. Now she had come to attend her older son’s funeral.

I started to plan the next steps: texting my dad to say we had arrived safely, getting a taxi to the rented flat, a visit to a local shop to buy coffee and bread. My thoughts were interrupted by a group of strangers who approached us and started saying something. The only word that got through to me was “condolences.”

The people who met us—a woman with a child (I kept thinking that he should have been in bed at such a time of night) and a man in a uniform—asked us to take a seat in a deserted airport café; it was already after midnight. The woman and the uniformed man introduced themselves and started to explain something about the next few days. I really struggled to concentrate, but I knew I had to focus. I looked through my handbag and pulled out a small notepad I normally carried with me on research trips, took out a pen and started to write things down, much like I did when arranging research interviews.

Monday

10 am – morgue on Pekarska Street.

[underlined]

Tuesday

11:30, [crossed out, replaced by 11:15] – morgue.

11:30 – go to the church. The church of Sts. Peter and Paul.

12:00 – service.

13:00 – Lychakiv cemetery.

[underlined]

“Enei” or “Eurohotel”

The people who met us had kindly thought of everything on our behalf, even potential restaurants for the wake: “Enei” or “Eurohotel” were recommended as the most suitable options, because they were not too expensive and within walking distance of the cemetery. I had never thought that the word “morgue” and “Eurohotel” would be written on the same page in my research notepad.

My notes continued with names, phone numbers, times and places. I have an annoying habit of opening my notepad on the first blank page I find and just starting to write there. My notes, therefore, end up being spread all through the notepad and sometimes written upside down. But in this case, it reflected my state of mind at the time much better than if they had been recorded neatly and methodically.

Liuba. That was the name of the woman with the child who should have been in bed by now. Liuba looked like a woman you’d like to have a drink with: lively and energetic. She was roughly my age and so mature enough to face up to whatever life threw at her and young enough to have the energy to deal with it. Her eyes were those of a woman who had seen pain. If not her own, then certainly that of others. Plenty of it. She made us as comfortable as she could, given the circumstances. Liuba was the one who told us exactly what to do, where to go and whom to contact if we had any problems. She gave me her mobile number—in my notes it was highlighted in blue—and told me that I could get in touch any time. She meant it. I didn’t quite get what her job was, other than the fact that it involved helping families like ours, even if this entailed dragging her child to all sorts of places at all times of the day or night. The little boy was patiently sitting nearby waiting for his mother to finish her working day long after it should have finished. As far as I was concerned, Liuba worked as our guardian angel from the moment we stood looking lost in the arrivals lounge and for some months to come.

The man in the uniform was called Oleh. I wrote his full name down in my notes but, in my mind, he remained “Oleh, the man in uniform.” He was working for the military commissariat. Much later, we learned that he had been working there when Volodya joined up. It was also he who would later present my mum with the Order for Bravery, awarded to my brother posthumously. Oleh was serious and officious. Like Liuba, he may well have been my age, but his stern look and the uniform made him look older. Having grown up in Ukraine in the 1990s, where the rule of law was not respected by law enforcement agencies, I generally don’t warm to people in uniform quickly. I prefer to avoid them at all costs. This man, however, somehow seemed approachable. Unlike Liuba, who did all the talking and explaining, Oleh didn’t say much. He looked at us patiently, silently and directly. He didn’t try to hide his eyes, although this situation was far from comfortable for him. I respected that. These two people made the days that followed just about bearable.

We finished our airport briefing, found a taxi and got to our rented flat. I thought I’d fall asleep out of sheer exhaustion, but I couldn’t. I had been told that my brother’s body had already arrived in Lviv. I was wondering where he was. My mum slept in the room next door and must have thought that I couldn’t hear her. But I could. Now and again, I would hear stifled wailing. Then silence. Then more quiet sobbing. The night passed somehow.

In the morning we sat in the kitchen before heading to the morgue, as noted in my notepad. Does one have a coffee before visiting the morgue? There was no question about breakfast. We wouldn’t be able to stomach it. I don’t remember if we had coffee. I don’t remember how we got to the morgue. I only remember meeting my brother, or rather his body, there. That was the first of the three things I dreaded most of all.