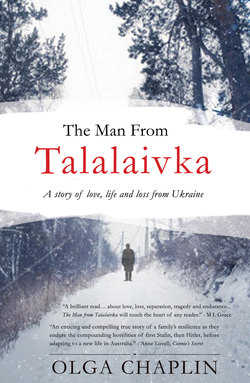

Читать книгу The Man From Talalaivka - Olga Chaplin - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 4

Peter hesitated, uncertainty edging him, as he recognised the dilapidated buggy in his father’s courtyard. Dismounting, he motioned to Mikhaelo to go into the farmhouse, forcing himself to contain his emotions as he prepared for Father Chernyiuk’s unexpected visit. He grasped at nearby grasses for the priest’s old tethered horse and leaned heavily against the crusted wall as he observed this creature of burden. The sun’s darting rays, captured in the courtyard, flashed at him, stinging his eyes. Even now, pain still blistered him. Two seasons ago, such elated joy … now, two seasons of unfathomable searing. In these few moments, in the privacy of his father’s courtyard, he held back a sob as he again felt the silent pain, yet forced himself once more to contain his emotions, to allow logic to rule his head, his being.

He looked again at the waiting farmhouse door and the visitor’s buggy. “He has not long called on us,” he murmured to himself, “there must be some urgency.” He felt angst for the old priest, reminded himself that he was not the only one suffering silently. The priest, too, had had recent reversals: a wanderer among his flock, ministering his faith as best he could, his ancient church of Kylapchin razed to the ground in the vindictive fervour since Stalin’s rise to power. The holy messenger of Orthodoxy was now without church or home, his community scattered, his means of survival precarious. His health was failing, but he nevertheless had accepted his fate stoically, without complaint. “How does he keep going, despite all this?” Peter searched for an answer. The elderly priest’s family was long gone: only his faith gave him the courage to pray each day, to await a better life.

Peter realised the political situation was rapidly changing in this uncertain summer of 1930, even more so than the psyches of the Ukrainian people of these regions could comprehend. Now, with the senior veterinary practitioner ailing, his own work took him even further in the area. He witnessed first hand the haphazard, iniquitous way in which collectivisation was implemented in their Oblast. The priest, like so many of his fellow countrymen, had become a pawn in the ensuing power struggle between Ukrainian farmers and Stalin’s apparatchiks.

This power struggle was not yet over, he suspected. Already in his travels he had heard of Lenin’s moderate protégé Bukharin’s demise; replaced, in these Ukrainian Oblasts, by the ambitious Kaganovich, who was once so devoted to Lenin’s ideals, but was now Stalin’s right-hand man in these regions, and given virtual carte blanche in honing collectivisation into unworkable models of excessive production. Peter feared for his father, who had earlier resisted the authorities, and who had worked so prodigiously with his entire family to maintain his productive farm. Ironically, the rewards for this effort and output were envy and jealousy, even vindictiveness from a regime increasingly setting impossible production quotas.

His horse nuzzled its heaving nostrils at his side, awaiting its master. He led his great, trusting creature to the water trough and rested his eyes on its magnificent frame and gently stroked its moist quivering shoulder. At last, he took the old jug from its stand, refreshed himself, drawing in a deep breath as he collected himself, summer’s hazy warmth brushing at cold droplets on his quenched lips.

He looked about wistfully at the countryside of his birth. To his left, at a short distance from the farm, Kylapchin lay hidden in a glen. The wispy spirals of cindered smoke from the remaining earthen ovens rising above the woods gave few signs of life. A pall hung over the once vibrant and industrious village as daily the soviet bureaucrats dispatched families to scattered kolkhozes, tearing the fabric of communal life. The village and its cemetery had almost merged, unable to withstand the onslaught of capricious officialdom and the politically engineered famine.

He gazed at his father’s full fields, the result of so much unrelenting work, and looked beyond these to the pinnacle of the hill lined with great trees, which delineated the new boundary of fields so hard-earned collectively by the family since Lenin had instigated his new economic policies. The sun’s rays glistened, deflected from the hillside, put a soft sheen over the artist’s vibrant palette that splashed before him: of golden wheat, corn, sunflower fields; trees, hedges, crops of variant greens; and wildflowers freely scattered in their reds and gold and blues.

Again, he breathed in its warmth and could almost taste the sweetness of summer’s early blooms, of the land’s generosity all about him. For a few suspended moments, he was transfixed by the beauty of this wondrous countryside, in awe of this idyll. Tears suddenly escaped his self-control. This was the soil on which he and his sisters and brothers were born, on which he was raised by his hard-working Yosep and Palasha, and in which his soul would one day be laid to rest. His gaze blurred: he could not dwell on this longer. Slowly, thoughtfully, he drew another deep breath, then sighed as if awaking to reality. He knew there was now no certainty in their future.

As he opened the farmhouse door, little Vanya ran to him. “Tato, Tato! Ve doma, ve doma!” Peter knelt down to his firstborn and kissed the soft infant face, gently tousling his dark hair. “You may play now, Vanya,” he encouraged him, watching as his son ran outside for his child’s play. He smiled, nodding gratitude to his caring mother.

“Ah, Petro,” his father’s measured tone greeted him as he stepped into the farmhouse. “Father Chernyiuk has just returned from the soviet committee. He wishes to talk with us, son.” Peter bowed in respect and received the old priest’s blessing, and joined them as they shared their grape wine and bread. He watched with heightening tension as the priest unburdened himself: the haggard, bearded face and dispirited eyes revealing the painful acceptance of his situation. “Both victim and messenger,” Peter thought, sensing the holy man’s dilemma, which confirmed his own inner fears that Stalin’s bureaucracy was now allowing officials almost total free rein in this region.

“What am I to do?” Father Chernyiuk suddenly burst out. “Am I to be both priest and spy?” he anguished. On pain of reprisal, the old priest was forced to join the local soviet committee, ostensibly to enable dissemination of Bolshevik Party policy, but in reality coerced to report on the very people who trusted him with their lives and souls. It was an almost untenable situation for this old messenger of Orthodox faith. Powerless, he could do nothing to alter this; he had little choice but to acquiesce. If he refused to co-operate with this sulphurous soviet committee, the consequences were extreme: imprisonment, labour camps, or execution awaited him.

Father Chernyiuk dropped his voice to a whisper, eyes widening in fear, as if an invisible enemy was already among them. Peter tensed, sensing danger. “Yosep, they are accusing you of being … a kulak! They use this false name glibly, so carelessly …” The words hurtled out as if the enemy had already thrown the hammer, about to crush them. Peter caught his breath, barely controlling his emotions, and looked at his stunned parents: Yosep and Palasha were being labelled kulaks by a local soviet committee, whose members’ only qualities lay in greed, envy and self-interest.

His heart sank, feeling their angst. All these years of back-breaking work by his family, even almost super-humanly meeting excessive quotas set by the officials, had come to naught. If anything, it had worked against them. Without the infamous kulak label, his Yosep and Palasha could have been considered as all the other small farmers, pushed into a nearby kolkhoz, to work as best they could. But now, as supposed kulaks, they would be deemed a danger to Stalin’s new Soviet society. It was ludicrous, but it was a clever label of convenience espoused by the very people of the soviet committee who sought protection from hard work and ostracism by mouthing Stalinist slogans in order to survive. He shook his head, grappling with the consequences. Somehow, he had to remain strong: his parents were too disturbed by their faithful messenger’s news. Father Chernyiuk’s information was only rumour, but instinctively Peter knew it was close to the truth of the situation. These were now dangerous times.

“Peta,” the old priest turned to him, speaking gently, his voice resonant with gravity: the voice of the Orthodox sage who had christened him and married him, his sad eyes determinedly meeting Peter’s. “You must prepare yourself, my son. The situation is changing very rapidly. You must plan for your little Vanya’s welfare. Peta …” he hesitated, choosing his words with care, the memory of Peter’s distraught face at Hanya’s funeral still fresh in his mind, “you must consider your duty to take a wife, my son … for your child’s sake, for your elders’ sake.”

Peter’s mind reeled. He was caught off-balance, unprepared for this counsel and the fast turn of events. “Come, Peter,” Father Chernyiuk continued, the mantle of his Orthodox faith imbued in him. “I must give you my blessing of dispensation from the mourning period. You must do this, my son, for your Vanya’s … for everyone’s sake.” He retrieved an old gold-embroidered ecclesiastical ribbon and small cross from his black shabby cassock and placed his hand on Peter’s bowed head. Incense on holy ribbon mixed with the mustiness of heavy cassock, confusing his senses: holy reverence, harsh reality, bore down on him. For a few moments, the farmhouse and its occupants were transposed by their priest’s solicitations and liturgical verse. Peter closed his eyes, forced himself to be inwardly strong, uncertainty encircling him. At that moment he could not allow himself to think of his Hanya and Mischa. The pain of these past months was too raw, too real. “But how do I tell this heart to not bleed … to heal?” he cried silently. He knew not how he would make the transition from widower to husband.

He stood in the old cobbled courtyard as the priest’s buggy made its way towards Kylapchin and beyond, and watched as the afternoon haze shimmered and enveloped the visitor as he disappeared behind the swaying corn and sunflower fields. He stood there for some time, pensive, capturing this remaining moment of permanence and security in his family’s farmhouse. He feared that his life, and his parents’ lives, were about to change at a faster pace than he could have envisaged. The uncertainty he faced, though precarious and unclear, was bearable, tolerable. But the uncertainties his parents faced were dangerously menacing. His skin pricked with anxiety: he sensed it would not be long before they would have their answer.