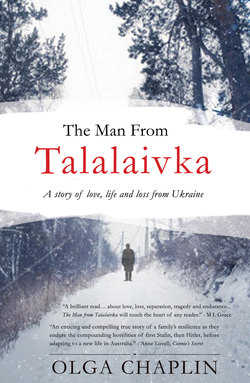

Читать книгу The Man From Talalaivka - Olga Chaplin - Страница 19

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 13

February 1932

Evdokia leaned her aching limbs against the solitary window of the kolkhoz farmhouse, knuckles white as she clung to its withered frame. Paralysed with anxiety, she waited. Her eyes searched the perimeter of the vacuous fields, in vain. Nothing stirred. The Ukrainian mid-winter ghost had passed over them, had dragged a blanched canvas over the depleted countryside. She longed for the familiar outline of her husband’s horse ploughing the snow, carrying its master. Tears escaped her. She did not know how many days she had left, her body now beyond trembling from the gnawing hunger it had endured each agonising day. “Boje,” she prayed silently, “Boje, daue miniue shche sely.” Her only hope, now, was that Peter would return to them in time.

Though daylight still beckoned, a pall hung over the kolkhoz farmhouse. Whatever victuals scraps remained were furtively hidden from other hungry eyes as each family struggled to live. Acrid vapours from a simmering watery broth permeated the hushed dwelling, testimony of the kolkhoz workers’ desperate plight. Already, the weak and sick had been taken from them, buried in haste by others still strong enough to carry the bodies.

She winced as her forehead pressed against the blank window, the icy sting of the pane a reminder of the chilling effects of collectivisation. Stalin had indeed exceeded his own dizzy heights, raping the Ukrainian black-soil regions of everything edible. His contradictory orders had come so abruptly, no kolkhoz worker could be prepared. Cruelly, his henchmen and soviet cadres had again ravaged the countryside with their ‘excesses’, on the spurious pretext of finding illicit samohon on St. Nikolas’s feast day. Backed by armed soldiers, they had removed every last grain and morsel of food, over-filling the silos of industrialised areas to rotting point. It was a bitter irony that at the very time of celebrating Christ’s birth, these regions experienced only suffering and death, so carelessly and haphazardly meted out to those least able to withstand it.

Vanya pulled at his stepmother’s limp body. “Mama, Mama,” he whispered through the weary silence. “Mama … can I have their soup? I’m hungry, Mama …” Evdokia forced back her tears and stooped slowly. Weakened eyes met the innocent, hungry child’s eyes. “Not yet, Vanya, not yet. We will make our own. There is still time before the snow comes.”

She braced herself at the open door, the numbing cold reminding her of the short but perilous journey. In her weakened state, she could not be certain she would find enough strength. She picked her way slowly, her worn boots crunching the crisp snow as they imprinted on indistinct outlines of footprints that had wended towards the ancient cemetery with the last victim. She turned from the snowy pathway to the white-laden thicket; fell on her knees and crawled beneath its heavy mantle. Her hands searched among the moist debris. She could not return to the farmhouse with bucket empty. She had to do this for Vanya, fill his aching little body with whatever edible growth she could find; will herself to live, for Vanya, for Peter, for their unborn child.

Her frozen fingers searched the sodden undergrowth for grasses, leaves, seeds from long-harvested sunflowers. With her remaining strength she pulled at the rotting tufts, cold reasoning telling her she would not return. Pain seared through her body. Faint with exhaustion, she held a handful of new snow to her mouth to stifle her sob, her warm tears cutting icily short on her freezing face. In her weakened state, she could not trust herself with the bucket. She watched anxiously as little Vanya carried it before her and dragged herself back, her eyes locked to the safety of the farmhouse door.

Slowly, like a sleepwalker in the dimness of the dwelling, she prepared their broth. Her fingers searched for a small cloth, hidden in the perena of their straw-stripped bed and carefully unwrapped the last grains of salt that would disguise the putrescent contents of the soup. She tasted the sour concoction and shuddered, but forced herself to consume it. The steamy watery mixture scalded their lips, but she smiled as little Vanya filled his hungry body. Their soup would last two days. She could not think beyond that. “Boje, miue Boje, prevezitue miue Peta do domy,” she prayed silently, hope almost gone that she would see Peter again.

With her last strength, she carried the broth to her corner; filled Vanya’s jug again, and placed it at their bedside. The cold timber wall numbed her back. She drew Vanya close to her, stroked his hair gently, and whispered for him to sleep. “Father, give me one more day; don’t take my soul yet,” she prayed to her Maker. Her last memory, of Peter’s straight back as he left with the soviet officials all those weeks ago, anguished her; the fear, that he would not return, became submerged as sleep anaesthetised her wasted body.