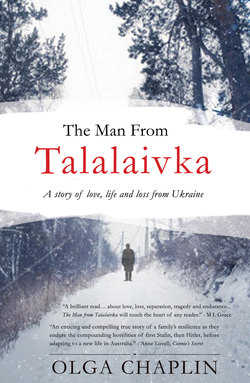

Читать книгу The Man From Talalaivka - Olga Chaplin - Страница 20

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 14

Peter reeled back in horror as he stepped into the farmhouse. The smell of death hung in the acrid air. Panic seized him. His eyes searched the dim corner for Evdokia and Vanya. “O God, don’t bring me this!” he begged, his mind flashing to earlier memories, to the tragedies of Hanya and Mischa. He stumbled forward, stopping to gently touch the elder’s shoulder as he wept at the babushka’s body. Unshaven for days, he had travelled at first light from the last village of his conscripted veterinary duties. He had seen hunger and deprivation in other kolkhozes as he and the soviet officials salvaged what was left of the livestock in the area. But he had not expected death to so completely ravage his kolkhoz farmhouse: sufficient grain and winter food had been allocated by the bureaucrats overseeing their kolkhoz. His own daily ration of black rye bread and other scraps was barely adequate, had left him gaunt but still healthy, the vodka in his small flask his reward as he guided his horse homeward in the snow.

Trembling, he knelt at their bedside, steeled himself as he lifted the heavy perena. Little Vanya blinked, momentarily afraid of the wild-eyed, unshaven stranger. “Vanya, Vanya … yak te? Te harasho?” Peter whispered. His little son smiled, reached out for his father. Peter carefully lifted him from the bed, then felt about for Evdokia. He felt sick with tension, fearing the worst. She lay motionless, in foetal position, in a coma-like state, her stomach swollen beyond endurance. Her body had reached a last stage, its final reaction to its unbearable condition before death released it. She was barely breathing; but she was still alive. Hastily he warmed water, added a few drops of vodka. His strong arms holding her, he fed tiny spoonfuls of the warming liquid to revive her.

Evdokia sensed her husband’s presence, but was unable to acknowledge it. She was hallucinating: the unshaven face of a grim reaper was tempting her towards him. Painstakingly, Peter persevered until the mixture warmed her. At last, her weakened eyes met his as he desperately watched her every movement. “Peta, Peta …” she whispered inaudibly. He felt choked with emotion, but held himself fast. He could not break down now. His wife’s condition required urgent action. She was too close to death. Searching deep in his coat pocket, he found a crust of rye bread. He soaked it and gently implored her to eat.

He stood up, his head spinning with tension and exhaustion. He had not eaten that morning; but he was still strong and fit. His ordeal had been one of weeks of slavish work and persistence in his duties in winter’s harsh conditions. He could not afford to delay, even for a moment. Pleading with officials would be futile. With Bukharin’s removal, Lenin’s liberal ideals were now truly extinguished. Stalin’s posse of yes-men, led by Voroshilov and Khrushchev, had put paid to humane considerations. Few would believe that their soviet counterparts were over-zealous and excessive in their cruel and perverse execution of Stalin’s latest orders. Even fewer would care to arrest the starvation and misery, and to amend their orders, upon risk of being labelled ‘kulak supporters’ by those ever watchful to demonstrate their loyalty to Stalin’s demands in his collectivisation madness.

Peter knew what he must do. He kissed Evdokia’s cold forehead, and whispered gently, “Hold on, Dyna, hold on … I will find bread. Don’t be afraid, you will live, my dearest wife.” Carefully, he removed her simple wedding band, gold cross and tiny ear-rings, wrapped them in a cloth and hid them deep in his coat. He comforted Vanya and emptied the last of the sour broth into his little son’s jug. He steeled himself, uncertain that his horse could withstand the journey to the illicit gold trader, and return him to Evdokia in time.

* * *

In the semi-dark of late afternoon, he quickly worked the precious milled flour procured from the trader and added a little fresh hay and drops of oil. He watched intently as the tiny kykyrhyske baked in the ancient earthen oven. He counted each one; life-saving rations for his little family. In the darkness of night, he hid the box high in the rafters. He had to ensure the contents would not be stolen; had to avoid Evdokia’s searching eyes as he rationed each kykyrhyska to her and Vanya in order to keep them alive.

Evdokia was to eventually recover from her ordeal: her ravaged body pushed closer to the abyss of death than she could acknowledge, in the horror ghoulish winter of 1931–1932. No external scars were evident, as she slowly regained her strength to return to the kolkhoz fields in the spring. Uncomplainingly, she accepted the penalty of quarter-kopeks docked by the kolkhoz overseer for gnawing raw beet hidden in her pocket. And she could look admiringly, in wonder, at her resourceful and energetic husband, who had returned to her and had found a way to save her and little Vanya.

But internally, the wounds remained. The internal scars never left her. Death had stared her too closely in the face, had permeated her body, had extracted almost her last breath. She could not—would not—ever forget this, ever inwardly overcome this. From that winter, she was a changed woman, her spirit scarred beyond repair. She replaced it with the mantle of caution, of practical considerations, and wore this mantle, permanently, to the very end.

She would never again allow herself to explore and experience the joy of an unfettered creative spirit. For such a decision, the price was high. Too high. It was as if, in some ghoulish way, Stalin’s poisonous chalice had reached her after all. She never again raised herself to the idealism she had earlier shared with her husband, the altruism and love of life that still fuelled him every joyous day. Though neither of them could have known it, they had already embarked on different spiritual paths in life, crisscrossing at times, but never truly sharing, experiencing, the same ultimate, beautiful moments. For that, she had Stalin to thank.