Читать книгу Schizophrenia - Orna Ophir - Страница 11

The End of a Diagnosis?

ОглавлениеWhile in the late 1960s Tony Wilson could be diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia, coded 295.3 by the 1968 version of the American Psychiatric Association’s DSM-II,16 this diagnosis is no longer permitted by the newest version of the manual (the 2013 DSM-5). Is this to say that there are no longer any “paranoid schizophrenics” among us? Have these individuals changed their nature? Or rather, has psychiatry changed its way of classifying and ordering disturbances in human psychological behavior?

Given the fundamental uncertainty that now surrounds the idea of carving nature at its joints when it comes to mental illnesses, most psychiatrists tend to reach their clinical diagnoses and proposed therapies by cutting to the chase, as Dr. Brewster did with Tony. After all, as The History of Nosography aptly noted in 1923, most physicians “cannot live, cannot speak or act without the concept of morbid categories.”17 They have no choice but to chop up the organic whole of mental illness into ill-defined parts, at times like clumsy butchers. Whether in the research lab or clinic, to make a diagnosis, psychiatrists are driven by their own pragmatic and bureaucratic needs, in addition to the urgency of their patients’ suffering. Furthermore, patients and their families – like Tony’s – are often just as eager as psychiatrists, in wanting a clearly defined, definitive, medical category. A diagnosis gives one something to hold onto, to replace the perplexing and, at times, terrifying experience of mental illness.

In his 2007 book, Our Present Complaint: American Medicine Then and Now, historian of medicine Charles Rosenberg argues that “the act of diagnosis links the individual to the social system.”18 Not only does a diagnosis serve a bureaucratic need (keeping records, setting up reimbursements, coordinating between professionals and institutions), it also serves an emotional necessity, offering patients and their families the security of a narrative. It gives a sense of solid ground to stand on, where previously uncertainty and anxiety prevailed. Patients want to know what they are suffering from: “What is wrong with me?,” as Anisha asked Amy June Sousa, who conducted her fieldwork in Lucknow, India, “Do you know if my illness has a name?,”19 she persisted. Or just as another patient diagnosed with schizophrenia who otherwise was not entirely comfortable with the diagnosis of the disease wrote: “The label has helped me, though, to feel less guilt about my inability to ‘conquer’ my problems, and to learn to make some allowances for my difficulties in handling situations.”20

In his book, Rosenberg describes diagnoses as passwords that grant access to the institutional software managing contemporary medicine. In this way, a diagnosis connects the individual to the collective, and vice versa. The problem, however, is that diagnoses then become “part of reality as much as our clogged arteries or dysfunctional kidneys.”21 In other words, for all its shaky grounds, not only does the clinical classification become “real,” but from there on, it wields a tyrannical power over our minds. This is fatefully illustrated by the astonishing willingness of physicians and psychiatrists to keep using categories of so-called “nosologies,” despite the wealth of clinical and therapeutic reasons to doubt their fundamental validity.

Dr. Brewster and other clinicians who still use the DSM understand this end of a diagnosis. Significantly, the DSM itself – also known as the Bible, the Rosetta Stone,22 and even the Chinese Menu23 of psychiatry – changes every few years, introducing new categories and putting an end to earlier diagnoses. Indeed, diagnoses are removed from the DSM when they fail to stand the test of time, that is, when the accumulated critical experience of doctors, patients, and families calls for a fresh look and a revision of previously established criteria. Collective disappointment thus produces a renewed effort to identify and classify madness or mental deviance – including schizophrenia – which then allows for completely new ways of diagnosing them. Together with disorganized schizophrenia, catatonic schizophrenia, undifferentiated schizophrenia, and residual schizophrenia, the diagnosis of paranoid schizophrenia became obsolete in the DSM-5. Formally speaking, there are no longer any “paranoid schizophrenics” among us. Since 2013, the kind or type of people (genus and species) that Dr. Brewster had labeled Tony with is nowhere to be found.

According to Hacking, the human sciences (including psychology, psychiatry, the social sciences, and clinical medicine) are driven by nine engines of discovery, and involved in a process of “making up people.”24 By counting people (say, 1 per 100 people in America suffers from schizophrenia); by quantifying them (age of onset before 45, duration of psychotic symptoms longer than a month), by creating norms; by correlating data about them (schizophrenics are 10% more likely to die of suicide); by medicalizing, biologizing, and geneticizing these subjects while trying to normalize deviance, by bureaucratizing these individuals, they invent new kinds of people. When “autistics,” “hoarders,” “the obese,” or “paranoid schizophrenics” emerge as new kinds of people, new types of experts who then identify, assess, and treat them, also appear. Newly instituted organizations then develop, which are specifically set up to cater to these new kinds of people, or patients.

While it was possible to be a “paranoid schizophrenic” after this kind of person was made up by psychiatry in 1968, this is no longer an option after 2013. With the change of the “ecological niche,” the conditions no longer exist for this specific diagnosis to thrive. It thus disappears, in what could be termed a process of “unmaking of people.”25

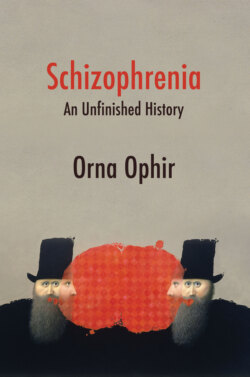

The present study and its title, Schizophrenia: An Unfinished History envisions the end of this diagnosis, with the double meaning of end as both the purpose of a diagnosis, and its possible termination or demise. Modern psychiatry has moved from carving out categories of mental illnesses to delineating spectra of these disorders, which is considered a remarkable paradigm shift in its classification system. In this book, we will examine whether this shift from a qualitative categorical diagnosis (based on descriptive symptoms) to a spectrum-like, dimensional classification (based on biological or psychological dimensions and scales) is at least partly responsible for the effort of bringing an end to the diagnosis of schizophrenia.

Since the 1990s, epidemiologists, psychiatrists, historians, and journalists have all been asking if schizophrenia is disappearing as a medical diagnosis. An article in the Epidemiology section of The Lancet, titled “Is schizophrenia disappearing?” suggested a substantial decrease in the reported incidences of schizophrenia since the mid-1960s.26 By the same token, a 2012 book titled Schizophrenia Is a Misdiagnosis criticized the validity of the diagnosis and announced its end.27 Other articles appeared with titles such as “‘Schizophrenia’ does not exist,”28 published in 2016 in the British Medical Journal, and “The concept of schizophrenia is coming to an end,” published in The Independent in 2017. This latter piece stated that schizophrenia might face the same fate as dementia praecox, the very diagnosis it had historically come to replace.29 Lastly, in the Schizophrenia Bulletin, a 2017 article suggested that the word might eventually be confined to history, not unlike the medical use of the term “dropsy.”30