Читать книгу Schizophrenia - Orna Ophir - Страница 12

A Difference in Kind or in Degree?

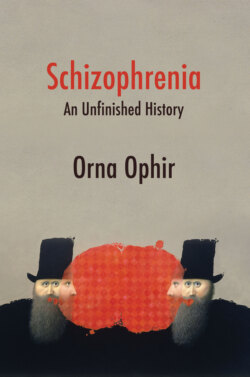

ОглавлениеSchizophrenia: An Unfinished History, then, aims to investigate two opposing ways of understanding mental health and its abnormalities, that have framed our perception from antiquity to the present day. Each of these views is paradigmatic, with different sets of shared commitments, practices, symbolic generalizations, models, and so-called exemplars.31 The first, which we will call the categorical view, characterizes abnormal mental states and behaviors as different in kind from normal ones, just as elm trees are different from pine trees, and trees, more generally, are different from minerals or from animals. The second, the clinical-dynamic view, defines the difference between normal and disordered states as one of degree, placing it on a spectrum within a wider dimension of mental phenomena, in the same way that in medicine hypertension is different from hypotension.

These two intuitions (of a difference in natural kind – of given qualities, or essence, on the one hand – and in degree – of quantitative, scalar variations, on the other), have produced two very different ways of representing mental health and sickness. As distinct and, at times, irreconcilable ways of seeing and talking about mental illnesses, they rise and fall, in response to the different social and cultural milieu in which they are discussed, and intellectually or institutionally supported. One of the aims of this book is to ask whether we currently find ourselves in a milieu or climate that may provide the conditions for the disappearance of schizophrenia as a helpful critical and clinical term of diagnosis and treatment.

Several experts attribute the decline in the reported incidences of the diagnosis of schizophrenia to the growing availability of better psychopharmacological treatments, while others place more emphasis on reduced accessibility to the treatment centers that record these numbers, or even to higher rates of suicide. Still others argue that the underlying cause of this decline is not so much due to a reduction in the number of individuals who exhibit what psychiatrists came to define as symptoms of schizophrenia, but to a dramatic change in the classification culture of psychiatry as a medical professional discipline. The “twin pillars” of psychiatry’s nosology (which provided the conditions for the birth of the term schizophrenia) are crumbling, some argue, and a new biomarkerbased classification system should be reconstructed, brick by brick.32

It is important to keep in mind, however, that the vast majority of authors who criticize the diagnosis of schizophrenia agree that some individuals indeed do experience delusions, hallucinations, and disorganized speech that make them sound irrational. They admit that such individuals may also exhibit disorganized or catatonic behavior, flat affect, or the failure to maintain basic self-care. And yet, a growing number of authors maintain that, as a presumed disease entity – as an identifiable state, a natural kind – schizophrenia does not “exist.” And while some claim that it could be considered and called an “end stage” of other untreated mental disorders (in the same way that heart failure is the terminal stage of various heart diseases), others won’t even go that far, proposing instead to abolish the term schizophrenia altogether.33

To this day, the integrity of schizophrenia as a diagnosis is unproven, as there is no valid objective test for it. The failure to identify schizophrenia’s biological markers, despite volumes of accumulated research data, has led professionals and laymen to propose discarding the label, both as a useful term, and as a biological or psychological category in its own right. Unsurprisingly, others have argued that to discard the concept and diagnosis of schizophrenia altogether would be premature and, hence, unwise and impractical. Indeed, it would represent a radical shift away from the current, predominantly categorical disease model of psychiatry, whose scientific and medical credentials (not to mention, institutional presence and prominence) are still largely unchallenged, forming a public and political reality to be reckoned with. As an alternative to the categorical method, the dimensional model still faces an uphill institutional battle to establish itself as a paradigm that carries similar weight in classifying mental illnesses. Yet, several examples and practices of this alternative model can already be found.

One such example is the diagnostic approach developed by the American National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), the largest research organization in the world specializing in mental illness, whose mission is to study, understand, and treat mental illnesses – and thereby, to pave the way for prevention, recovery, and cure of these ailments. The NIMH’s “Research Domain Criteria” (RDoC),34 although intended as a research framework for new approaches to investigating mental disorders rather than a clinical diagnostic guide per se, aims to explain mental health and illness in terms of varying degrees of dysfunction in systems of emotion, cognition, motivation, and social behavior. The RDoC tries to identify basic dimensions of medical and psychological functioning that span the whole range of human behavior, from normal to abnormal. This shift (from distinct categorical diagnoses to a more dimensional approach) is arguably the result of what Richard Noll described as psychiatrists’ increasing realization that “pouring muddy water from one jug into another” would not make it clearer. An alternative and, in their eyes, better “solution” would be “to break the jugs” instead.35

Another example of a dimensional system of evaluation is the “Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology” (HiTOP).36 The HiTOP was developed by a group of psychologists and psychiatrists from several research centers, with the explicit purpose of offering an alternative to the neurobiologically oriented RDoC. The HiTOP regards mental health as a spectrum. It places mental health problems on a continuum between pathology and normality, in much the same way that we measure body weight or blood pressure. Just as human weight is measured on a numerical scale (from 1 to 250 kg) and blood pressure on a different scale (from, say, 40/70 to 100/190), according to the HiTOP, we can also find a spectrum ranging from normal to abnormal when it comes to memory, perception, attention, social communication, and the ability to regulate fear, loss, or rewards.

The old classification system of the DSM used a top-down approach, defining mental disorders on the basis of their symptoms and presuming underlying natural causes with their corresponding effects. In contrast, these recent models begin by defining the normal distribution of a given trait or characteristic. Only then do they consider what might cause a gradual dysregulation or dysfunction in these systems that might result in symptoms in need of eventual diagnosis and treatment. Instead of looking for delusions, hallucinations, thought disorders, disorganized speech or behavior (or any other symptom that supposedly “make up” schizophrenia as a given entity), they search for domains that span this continuum ranging from the normal to the pathological. In these domains, we find a host of phenomena, mental states, and episodes, which include fear, frustration, learning, perception, memory, language, attachment, communication, understanding of self and others. The aim is thus to avoid setting arbitrary boundaries between health and pathology, normal and abnormal, which in current systems run the risk of being taken as natural kinds. These alternative diagnostic models begin by looking for the basic building blocks of the psychopathological structure, and then work their way upwards to its highest level of generality (HiTOP). In sum, they presuppose that psychopathology is dimensional in nature, while still allowing for categorical diagnoses where these are useful for pragmatic treatment purposes – and, more specifically, to help patients secure disability benefits.

Suggestions for revising existing diagnostic practices have also been proposed by scholars outside of the mental health professions. For example, Nikolas Rose, a British sociologist, spent decades questioning the psychiatric enterprise and defending a move from “diagnosis” to “formulation.” According to Rose’s distinction, a complex story (one that includes the causes of the person’s distress and that follows how their experiences might have penetrated “under their skin”) would be just as appropriate in clinical practice as using a “name” to label a categorical diagnosis. Moreover, assessing the person’s capabilities and impairments would be much more useful when planning their needs for receiving mental health services. The move from labels like “schizophrenia” to a story told about the person’s overall situation and station in life, the biological, psychological, and social factors that have caused and shaped their ailment and suffering, and the identification of their required current care, would demand more listening on the part of everyone involved. Such listening, Rose argues “would be all to the good.”37

Other voices in this larger conversation want to bring the diagnosis of schizophrenia to an end for very different reasons. Some psychiatrists, psychologists, social activists, survivors, ex-patients, and others have argued that the label “schizophrenic” is stigmatizing, due to the connotations of hopelessness, chronicity, and even dangerousness, that it carries. In response to this and to patients’ suffering, they seek alternative, less discriminatory, and more appealing, diagnoses. “Extreme mental states,” “voice-hearing,” “non-ordinary states,” or “diverse identities” are but a few of these suggested alternative designations.