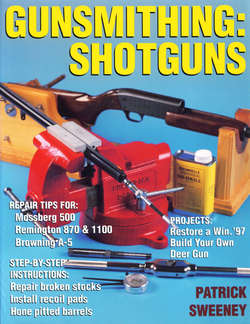

Читать книгу Gunsmithing: Shotguns - Patrick Sweeney - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 3 Tools, A Place, and Practice

“Give me a place to stand and a lever long enough, and I can move the world” Archimedes

Give me a comfortable bench and enough light and I can take apart any shotgun and fix it. If you are going to work on your shotguns with any comfort you are going to need a place to work. Something a little larger and more sturdy than your lap is required. I have disassembled, cleaned, repaired and inspected shotguns with no more than a shop apron spread over my lap, but it wasn't by choice. You bachelors out there, do not get too attached to using the kitchen table. As soon as you find someone willing to put up with you, the kitchen table will become forbidden territory for gun work. Besides, do you really want the lubricants, solvents and powder residue working its way into your food?

Your workspace must be well-lit. The overhead fluorescent light gives good tight, and the white watt next to the bench adds an even reflection. The dehumidifier next to the bench is a good idea in some climates. Arizona residents need not bother.

First, there should be light. You can't work in the dark, and you can't work very well in the typical gloom of a basement, garage or spare room with only a centered ceiling light. A fluorescent fixture over your bench will fill the area with even light, without being too bright or hot. You'll need additional light, in the form of a flexible desk lamp. The desk lamp can be positioned and angled to shine directly into an area as you're working. Rather than fish around inside a receiver by Braille, you can shine the desk lamp into it and see what's going on.

You need a sturdy bench. The bench can be in a spare room or large closet, in the basement or the garage. It should be solid wood, not particle board. You can build a bench from lumber or heavy-duty steel shelving. One of my workbenches is made from lumber. It came as a ready-to-assemble kit from one of the “big box” stores. I also used shelving rated for 1,500 pounds per shelf, and stiffened the tops of both benches by laminating plywood to them. The particle board shelving that came with the steel frame is sturdy enough to hold things, but not sturdy enough support a vise. You should have a vise. A solid vise holds parts securely while you are filing on them, measuring them or using a tap or wrench on them. A good vise is a more solid arrangement for holding parts than the strongest person you know, and you don't have to worry about missing the part and hitting your buddies hands if the part is in a vise.

In addition to the overhead light, a flexible desk lamp adds light just where you need it. Notice the fire extinguisher on the end of the bench. Keep it close at hand when soldering.

Bench height and vise height are important. The bench should be high enough that its working surface is a couple of inches above your wrist when you stand next to it. If you have to bend over to grab something off of it, it is too low. Vises are designed to stand on top of a bench of the proper height. Depending on your height, you may have to vary the height of the bench when you assemble it. At the proper height, you do not have to bend over even the slightest to pick something up off the bench, or to file something in the vise. The easiest way to find the correct height for YOUR bench is to work on a bunch of different ones and see if they cause you pain. A low bench will cause a stiff back, while a high bench will tire your arms and cramp your shoulders.

You want a solid, sturdy bench. This one has been stiffened by laminating plywood to its top surface. The vise on its overhang has been given additional support with a post. The bench is kept in place by storing ammo on its lower shelf.

A solid vise is a must. This medium-duty one is up to all tasks short of unscrewing a rifle barrel. As the bench isn't up to that either, the barrel vise has its own steel post elsewhere.

If you are going to do some work on your gun at the range, a small vise you can clamp to the bench is very useful.

This heavy-duty vise is everything you'd need.

A cleaning cradle lets you work on your shotgun without having to clamp it in a vise, or hold it in your hands or lap.

An additional holding tool you will find very useful is a cleaning cradle. Not so much for cleaning the barrel (unlike rifle barrels, on most shotguns the barrel comes off) as for scope mounting and working on the beads. Growing up, I learned cleaning and disassembly from my father. He learned from the Army, who taught him how to strip and clean a whole bunch of firearms, none of which were shotguns. And all this stripping and cleaning was done without a bench or cleaning cradle. My first day as a gunsmithing apprentice I looked at a cleaning cradle as if it had been beamed down from the starship Enterprise. By the end of the day I was converted, and would not be without one again.

With a bench and vise in your workshop, you next need disassembly and cleaning tools. A good set of screwdrivers is a must. The standard home screwdriver blade is too soft, too narrow, and too tapered to work on guns. The soft metal is cheaper and less likely to break, but deforms under a load. The narrow tip ensures it fits into any screw slot in the house, but defoms the edges of screw slots on guns. The tip's taper also ensures that it “fits” every screw slot, but acts as a lever to pry the screwdriver up out of the slot of a frozen screw. Unlike a home screwdriver set, which has four or five sizes, a gunsmithing set will have two dozen. A proper blade is hard. A hard blade will break before it bends, and not deform under a load. You should select a screwdriver blade that properly and tightly fits the screw on which you are working. And the tip must be hollow ground. The sides of the tip of a gunsmithing screwdriver are parallel. Unlike the home screwdriver which levers itself out of the slot, the gunsmithing screwdriver transmits all of its force to the screw.

Professional gunsmiths commonly grind their own screwdriver blades. With a drawer full of candidates, if the working screwdrivers on the bench do not fit the screw at hand, they will pluck one out of the drawer and grind it to fit. As one example, Browning shotguns in general, and the A-5 in particular, will have screws with very narrow slots. You will have to grind screwdriver blades to fit. Even a gunsmithing screwdriver set with two dozen tips will not have any narrow enough for the Browning.

The best investment is one of good screwdrivers. A full set like this B-Square will work for 90% of the things you'll need.

Likewise, take your cleaning cradle to the range to aid in cleaning while testing.

Household screwdrivers (the gray one on the right) are not meant for firearms. Either invest in the correct screwdrivers, or modify standard ones to fit.

To grind your screwdrivers, the best tool is a bench grinder. However, bench grinders are noisy, heavy, expensive and messy. You can use a hand-held grinder to modify screwdrivers. Use a sanding drum in the grinder. Clamp the screwdriver in your vise with the tip sticking up 3 or 4 inches. Brace your hands against the vise and use the drum to narrow the tip and keep the sides parallel. Do not overheat the tip or you will soften it. If the tip turns blue, you've overheated it. The two solutions to a softened tip are to either heat it in a propane torch and quench it in oil, or grind the shaft back to hard steel and then grind a new tip in it.

You can see the rounded tip of the household screwdriver on the right. The gunsmithing screwdriver has parallel surfaces, and the tip is square for an even “bite” in the slot.

In addition to screwdrivers, you'll need drift punches. While older shotgun designs have a plethora of screws holding them together, many newer shotguns are assembled with push pins. The Remington 870 and 1100 for example, have but one screw, and that holds the stock on. The only other part that is threaded is the magazine cap, and you don't need a screwdriver for it. The drift punches can be used with a hammer, or pushed by hand, to drift pins out.

Once you shotgun is apart, you'll need cleaning tools for it. The barrel will require a cleaning rod with brushes and patch holders. While on a rifle a one-piece rod of hard steel is needed, on shotguns you can use the jointed rod. There are three reasons to use a one-piece rod in rifles. One, the rod is a tight fit in the bore. On a shotgun, even if you used a half-inch bar as a cleaning rod for a 20-gauge barrel it wouldn't come close to rubbing. Two, the edges of the joints can scrape the rifling and wear it. On a shotgun, the rod won't come close to the bore, and for most barrels there is no rifling. Three, the soft rod in a rifle can hold grit in its surface, grinding the vital throat and leade of the rifling. Again, on a shotgun, the rod doesn't come close, and there usually isn't rifling to worry about.

This is a very nice set of screwdrivers and drift punches, in their own carrying case.

A jointed rod is easier to store. Along with the rod, store your brushes, patches and swabs. To clean the barrel you'll need at least a bore brush. The bore brush scrubs the plastic, lead and powder fouling in your bore. A chamber brush is slightly larger and does the same for your chamber. If you get a dedicated chamber brush, mount it on a short handle and leave it there, if the chamber brush makes a trip down the bore it will get squeezed down (the brass ones, anyway) and will not be useful as a chamber brush. With the short rod you can't forget which one is which. Many owners of Remington 1100s and 11-87s also invest in a gas ring or barrel hanger brush. This brush is used to scrub the inside of the gas system enclosure on the guns. Instead of the gas system brush, I use a degreaser to suck the oils out, and then wire wheel the crusted gunk off. The wire wheel is an extra fine wheel from Brownells that fits my hand-held grinder. With the gunk turned dry as dust, the wire wheel makes short work of any crusty gas system, and takes off any rust that might have formed underneath the gunk.

The Grace set, with properly-ground screwdrivers and brass drift punches. If you knarf your gun with these, you have no one to blame but yourself.

Here is a chewed-up screw slot. This is the result of using an improperly-fitting screwdriver.

With properly-fitting screwdrivers, no job is impossible. This Winchester was made in 1926, and probably hadn't been apart since then. The right screwdriver made things simple.

If you are drilling, you'll probably be tapping. You'll need taps and a thread gauge.

Taps come in three types, from right to left; taper, plug and bottoming. The taper is easy to start, and he bottom lets you tap to the bottom of a blind hole. The plug is for the inevitable compromises.

A minimum cleaning kit would be a rod and accessories and a cloth to wipe the shotgun down after you are done.

For the interior of the receiver and the trigger mechanism, a regular gun cleaning brush works fine. Usually with a green or black plastic handle, the original design of most brushes dates back to the introduction of the M-16.

All of this cleaning requires solvent. The customary method of providing a cleaning location and solvent supply is with a parts cleaning stand. The sink of the stand rests on a barrel of solvent, which is pumped up into the sink. The parts are scrubbed while in the stream of solvent. The solvent is usually mineral spirits, an inexpensive and non-flammable solvent that usually is reclaimed and has a small percentage of kerosene in it. Only the new, non-reclaimed solvent can be called odorless, and even it has a slight odor to it. Reclaimed solvent that has been used for a while will have a distinct odor to it. The odor is strong enough that on a regular basis we would have people walk into the gunshop and ask “what is that smell?” It wasn't objectionable, but it was noticeable. Even after I would drive home for over half an hour with the truck windows open (tough to do in a Michigan winter) my girlfriend would comment “You smell like a gunsmith.”

A parts cleaning tank, with compressed air nozzle for blowing the solvent off is fast, convenient and messy. The Bassett hound is an option.

Small nicks and scratches can be touched-up with this Outers kit. Extensive bluing requires more of an investment in time, materials and space.

The solvent-soaked parts would be dried by blowing them with compressed air. Between the splashes from the parts washing stand and the compressed air blowing the gunk off, the corner of any shop that uses this method gets dirty. No, it gets grubby and crusted with gunk. And when the drum of solvent gets filled with powder residue, oil, bits of rust and gunk, it has to be properly disposed of. Even as an enthusiastic home gunsmith of your own guns it will take years to use up a drum of solvent, but sooner or later you will. You cannot simply dump the stuff down the drain. If you have the elbow room and can stand the mess, go ahead with a parts tank and solvent. Otherwise, you'll need a different method.

Instead of the smelly mineral spirits, use Brownells d'Solve. It is a concentrate that you mix with water to make a cleaning solvent. Before you scream that water is the tool of the devil and will not come near your shotgun, consider that we will be using a blow dryer or heat gun to dry the parts, and penetrating lubricant to protect them. Mix your concentrate and scrub the parts in a sink or basin. Once clean, use the blower to dry them and immediately oil them with a penetrating oil to cover the parts and displace any residual water. You can filter the used solvent back into a storage jug, and when it is too nasty, cap the jug and take it off to the nearest landfill or recycling depot.

To scrub the bore you'll need bore solvent. Unlike the general cleaning solvent you will not need gallons of bore solvent. A quart will last you years. Keep the solvent in the bottle clean, and transfer the solvent to your cleaning patch or swab with an eyedropper or a clean patch. Don't just dunk the grubby swab or brush into the bottle, contaminating the solvent in the bottle. Unlike rifles, you will not need abrasive bore cleaning compounds to remove the fouling. The shotgun bore does not get exposed directly to copper as a rifle bore does. The only thing your bore is likely to see is plastic and powder residue. If you shoot slugs or buckshot, then there will be some lead. All of this will come out with a brush and solvent, or in extreme cases with a swab wrapped in brass kitchen cleaning mesh.

Which brings us to lubricants. Rather than petroleum-based lubricants I prefer synthetics. Petroleum-based lubricants are tough on wood. If your shotgun sits in the rack (as most do most of the time) the oils in it will settle in the rear of the receiver and come in contact with the stock. Petroleum products soaking into the wood soften the grain and lead to spongy wood that cracks. Synthetics will settle, but they won't attack the wood. I use Break Free, FP-10 and Rem Oil as light lubricants. For contact surfaces that need a more persistent lubricant, like sear tips and hammer hooks. I use Chip McCormick's Trigger Job. One jar will last a long time, even when you may have a bunch of guns to treat. My jar is so old it dates back to when he called it Trigger Slick, and I have used it on almost every firearm that came through the shop for work or repair in the years since.

Brownells d'Solve is a water-based cleaning solvent. Used in conjunction with a heat gun or blow dryer to evaporate the water, it is a convenient, odorless and non-toxic means of cleaning your shotguns.

Standard solvents and chemicals will do many things, but they won't strip old finish off. Especially the finish on Browning shotguns. Consider the cost of extra supplies if you want to do the job yourself or send it out.

If you are going to go past simple disassembly and cleaning, you'll need more tools. To strike some of the tools you'll need a hammer. A ball peen hammer of a medium weight, 8 to 12 ounces should be enough. For filing, the most useful file I have found is Brownells Swiss pattern, 8-inch extra narrow pillar file, #2 cut. It is large enough that you can get a good hold on it. It is small enough that you can get to places you couldn't with a large file. The #2 cut is a medium-fine cut, but the file can be used to remove large amounts of material and still finish with a smooth surface. The only drawback to the file is its flexibility. You can press on it hard enough to bend it, and if you aren't careful you'll file a rounded cut instead of a flat cut.

If you need a larger, heavier (non-bending) or coarser file, then get an American pattern Mill file, second cut of 8 or 10 inches long. It will be stiff enough that it won't bend, which is also useful as a backer when sanding.

For woodworking, get a cabinetmaker's rasp. The two files I mentioned are too fine for wood, and will fill up with wood after a couple of passes.

Buy as much lubricant as you think you'll need, and then some. You can get quantities from the ⅔ of an ounce to a full gallon.

To keep your files clean and properly cutting, get a file card. The one we're discussing is a flat piece of wood with short brass or bronze bristles used to card or comb the filings out of the teeth of the file. If you don't remove the filings, the file loads up and stops cutting. Before it stops cutting, the partially-loaded file cuts unevenly and makes a mess of the surface you are creating. The rasp will also need regular cleaning to keep your woodwork smooth.

If you are filing metal, filing talc makes the job messier but makes the filing easier. The talc slows down the accumulation of filings in the teeth of the file, reducing the need for carding. It also creates a mess. File the talc to load the file up, then file the metal. When you're done, sweep and vacuum up the mess, and wipe your shoes off.

For high-pressure areas such as sear tips and hammer hooks, a persistent lubricant is a must. Chip McCormick now calls his product “Trigger Job” but it still works great. A small jar is probably a lifetime supply.

Drilling holes requires drill bits, regardless of the kind of drill you are using. If you keep all of your drills in a small box, it is slightly better than letting them wander around on the bench. Keep them in small envelopes in the box, or get a drill organizer to keen them sorted and handy.

Hammers and drift punches are a must. Many shotguns will have pins holding things together.

You've got the bench, lights, vise, cleaning equipment and tools. Keep them organized. Don't “store” your tools in a heap on the end of the bench or in the corner. The cutting tools with get nicked and dulled, the polishing tools will get gouged and scratched and will not polish properly and your cleaning rods will get bent. At the very least, keep them in the boxes they were shipped in, and store the boxes on a shelf away from the bench. Better yet, get some plastic tool organizer boxes from the big-box hardware store or chain, and store your tools in the boxes. If you want, you can write an inventory list to keep track, but that is going a little overboard. Keep small accessory parts in a box and with the fixture they go to. Mark their box so you don't have to open it to remember what's in it.

Clean off your tools before you put them away. Card your files clean and wipe cleaning solvent off of the cleaning rods and tips before storing them.

You need the right file for the job. One file cannot do everything, but some come closer than others.

You should not leave your bench a mess. I did so in the past, but found a clean bench was much easier on the nerves. And, I could find things I had dropped!

For power equipment, the aforementioned bench grinder is very useful. But it is noisy, messy, loud and expensive. In the house the bench grinder is a hassle. The ground particles of metal combine with the grit from the wheel to make a persistent powder that not only gets rugs and floors dirty, but can grind the finish off a floor. With a sanding disk a bench grinder can be used in lieu of a belt sander to fit a pad, but the mess increases exponentially. The rubber dust of the pad flies around the room and gets on the walls, ceiling and the floor. You end up coated with the dust and track it wherever you go. If you have an extra bench in the garage you can exile the bench grinder out there and use it as needed, otherwise forego the bench grinder. An equally useful and more fastidious power tool is the drill press. The biggest drill presses have their own floor stand, but you can do almost everything on a model that stands on the bench. Make sure you get one that is tall enough between quill and plate, as the setup for drilling a shotgun quickly eats up space. At a minimum, you want a drill press with 14 inches between tip of the chuck and the baseplate.

A good tool chest is very useful for storing your tools, parts and fixtures. This Kennedy box is lockable and expensive, but even a cheap plastic box is better than an unorganized cardboard box full of loose stuff.

A variable speed drill is a must if you are going to polish your bore, chamber or chokes. To drill the stock for a pad installation, sling swivel installation or to repair a crack, it is indispensable.

And a hand-held grinder is vital for some repairs. A grinder like the Dremel tool, or my ancient grinder made by a company that went out of business before the Beatles broke up is just the ticket for fixing a cracked forearm.

The big machine tools are nice but beyond the scope of the home gunsmith. While a lathe or mill can be very useful for some jobs, you have to ask yourself a few hard questions. “How will I pay for this?” “How many jobs will I have to do to cover the cost?” and “How long will it take?” Even a professional may not invest in such equipment, if he (or she, let's not be snobby about this) cannot recover the cost in a reasonable time. Many gunsmiths send their own guns to other gunsmiths for work. You should not be bashful about doing the same. For all the years I was a professional gunsmith, I never considered welding. I had a couple of good welders nearby who not only knew guns but took directions well (an important consideration) and I didn't have the time to learn. And after all, the point is to fix your guns, not to learn how to become a lathe operator for the few times a year you might need the use of a lathe.

If you invest in a full parts cabinet, you can not only store all of your tools in one place, but you can lock the cabinet.

You will need some place to store all this gear, and a place to do your work. Even a simple disassembly and cleaning can create family strains if done on the kitchen table. Imagine the hell to pay trying to refinish a stock, or install some sling swivels! The best solution is a spare room in your house, or if you have a large and dry basement, down there. Set up your bench in a corner that is not obstructed with pipes, and has power outlets nearby. A spare room used as a gunsmithing room should have its own lock on the door. If you use a corner of the basement or garage, consider storage cabinets to get everything out of sight. If at all possible, use the basement instead of the garage. Garages are open to public view each time you enter or exit with your car. Cars bring water and dirt in with them. If you have extra tools, they are handy to force open your cabinets. Wherever you set up your shop, the guns themselves should be locked up. Even before the wave of litigation about proper storage, it was prudent to keep your guns locked up. Now, you may even have insurance requirements mandating it. A good safe will cost as much as a good gun, but will do what one more gun can't Protect the other ones. A good safe is going to be the size and weight of your workbench, and should be just as portable. That is, not at all portable. Buy a good safe, but don't worry about getting a fireproof one. A friend of mine had his house burn down, and his gun safes ended up sitting in the coals while the firemen hosed the smoldering embers. The guns were steamed but fine. One more strike against the garage: a safe in a garage sticks out like a sore thumb. It is obvious to anyone who sees it. Set up in the basement or a spare room!

For some jobs, nothing but a bench grinder will do. But it is noisy and messy. Best to use it only in a dedicated room, or banish it out to the garage.

One thing many professionals have that you won't need is a bullet trap. Used for test-firing, even this one with an exhaust pump and filter is messy. Be patient and schedule range trips for your test-firing.

If you'll look closely at the face of this bullet trap, you'll see the results of a four-shot burst from a malfunctioning .45 ACP. Messy and exciting!

Some things you can do with a hand-held variable speed drill. But there are many things you cannot, and for those jobs you need a drill press.

Between the dust from a bench grinder, belt-sander and bullet trap, this computer monitor has gotten so grubby it needs more than some light dusting. This is proof of the need for a dedicated space if you do more than just disassembly and cleaning.

A hand-held grinder can be very useful. When you buy grinding and polishing wheels for it, buy a bunch. If you break or lose your one-and-only, you'll have to wait until its replacement shows up.

For most everything you'll do, a bench-top drill press is enough. Make sure there is enough space between baseplate and quill to fit your fixtures.

Fixtures make jobs go faster and easier. This Williams scope mount drilling jig is just the ticket if you're going to drill and tap several shotguns. If you only plan one, it will be easy but expensive.

Taps require handles. Without the handle, you can't turn the tap with enough force to cut metal.

Do you really need the extra cost of a floor-mount drill press? Next to this one is a buffer & wire wheel. It is almost as messy as a bench grinder.

Soldering requires heat. Light jobs can be done with a propane torch, bigger ones require an acetylene torch. (Not to be confused with an oxy-acetylene welding torch.) Any time you are applying heat, keep a fire extinguisher on hand.

With a safe in your work room, bolt it to the floor or walls, and add weight to it. In addition to the bolts, a couple hundred pounds of lead shot ensures the immovability of your safe. And you do have to store your shot for reloading someplace, right?

The Learning Curve

The way to learn is to do. But “doing” for the first time on an expensive shotgun, or a family heirloom, can be a nerve-wracking experience. Rather than subject yourself to the tension, get a practice gun. Hike off to a gun show (assuming the powers that be in Washington let us do such things in the future) and walk the aisles. While an exact duplicate of your shotgun would be great, it doesn't have to be the same gun unless you are working on something type-specific. Don't worry about condition and features, because you will be using the new-old gun as your practice canvas.

If the paperwork is too onerous, or you just don't want to buy another shotgun, then pick up some parts. A stock and barrel will work as the bare minimum.

With your practice gun or parts on hand, you can work away to your heart's content, safe in the knowledge that whatever happens can't hurt your Dad's shotgun handed down to you.

With your own workspace, you don't have to worry about spilling oil and solvents on the kitchen table. A bench at the correct height makes the work less tiring. (The .458 in the corner is in case of marauding bears in the suburbs. The fact that there aren't any is proof of its effectiveness.)

A clean and well laid out work bench makes the work go easy.

A garage may be convenient, but it is also drafty, humid, open to observation, and not secure. Many garages are also cluttered even before you move your gunsmithing stuff in.

You should store your guns in a lockable container. For the cost of one gun, you can protect many. (Photo courtesy Remington Arms Co.)

Even a small and inexpensive safe is better than none at all. And in some jurisdictions, it may be legally and insurance-wise a necessary investment. (photo courtesy Remington Arms Co.)

Some things make life much easier. To remove a frozen screw without a screw jack is a big hassle. With it, the job is easy. If the screw resists the jack, then off to the drill press.

Buy good measuring tools and treat them properly. Store them in your tool chest and do not set heavy things down on them.

A couple of generations ago, if you wanted to be a gunsmith, the first thing you would have to do is make the tools of gunsmithing. Anything that wasn't a standard machine-shop tool was something you would have to make. Most gunsmiths still do the basic things, like grinding their own screwdrivers, but hardly anyone fabricates their own fixtures. Why would they? Unless it is a one-of-a-kind job, or no one has thought of it before, the hours of design and fabrication, testing and altering take up a lot more time than just buying the right tool. And the business has gotten so big that some shops only make the tools to do gunsmithing, having given up gunsmithing entirely.

If you wanted to find just the right tool for each job, you could send off for the catalog of every manufacturer of gunsmithing equipment and pore through them. You'd end up with a file about a foot thick, and you would still not cover them all. Instead of all that hassle, send off for the Brownells catalog. It will be the best five bucks you've spent in a long time, maybe ever. Not only will there be more goodies in it than you can afford without winning the lottery, but you can order them all from one place.

Brownells has been at it for a while, as the current catalog (in 2000) is the 52nd. In James V. Howe's “The Modern Gunsmith” (first edition 1934, last updated in 1954, and anything but modern now) Brownells is listed as a source of supplies. The list is not long, but they are at the top. As an aside, Howe was published by Funk & Wag-nail's, and I'd wager a very nice shotgun that it has been years since there was anything to do with firearms in their title list. The late Bob Brownell started offering other makers' tools and supplies right after World War II, and put together a catalog to list the goodies.

You can spend many an interesting evening just flipping through the latest catalog, and find something on every other page that may make you think “I never knew you needed something like that!” Once you have your list narrowed down, you can call, write or e-mail and expect your parts on your doorstep within a few days.

If you've ordered something, and the complete instructions just aren't clear enough, phone Brownells and ask for the experts. On hand will be experienced professional gunsmiths who have the best job in the world. They get to play with all the toys so they can explain anything you need to know. All of them have worked in gunshops or gunsmithing shops before they got the neat job of working with fellow gunsmiths and playing with the toys.

Tools and parts are grouped by their use or type of firearm, so you don't have to flip through the whole thing to find each entry for a particular application. Each entry includes a clear photograph of the part or tool, so you can see exactly what you are getting.

Recently Brownells expanded their offerings, and the catalog, greatly. They now offer factory parts for 17 different manufacturers. How I wish they had started back when I was working on guns for a living! Often, the price of a job was not dictated by the price of the part, but the price of the shipping and handling, or the minimum order limit from a manufacturer. Now, if you need a particular screw, pin or part for a shotgun, you can add it to your regular order from Brownells. What, you don't make regular orders from Brownells? Just wait.

If you can't find it in Brownells, you'll probably have to make it yourself. If you do make a useful gadget, Brownells may want to carry it. Brownells is Christmas catalog for gunsmiths and shooters. It costs less than a movie ticket and delivers much more enjoyment than many “Blockbusters” do.