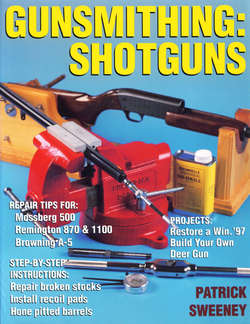

Читать книгу Gunsmithing: Shotguns - Patrick Sweeney - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1 History

Black powder was invented in China 1,000 years ago, but its first appearance in Europe came in 1313 by the hand of Friar Berthold Shwartz. Others may have developed it earlier, but they left no record, perhaps an inadvertent outcome of the discovery. (A valuable lesson: if you want to get credit, or prevail in the patent lawsuit, take good notes.) Reading about the first uses of gunpowder, and the “gonnes” it was used in, is enough to raise the hair on the back of your neck. The barrels were just that, barrels, made of wooden staves strapped into a tube. The “powder” was simply a mixture of the three ingredients of black powder, charcoal, sulphur and salt petre (potassium nitrate). After shoveling in an “appropriate” amount of their favorite mixture, the gunners would load the projectile, point the gonne in the direction of the enemy, and apply a torch or smoldering ember to the touch-hole.

The barrels split often enough that both sides of the fray kept a safe distance. Rifling, what rifling? After all, how can you rifle a wooden tube, what good would it do when the “bullet” is a stone? You really had to dislike someone to go to all that effort for not much gain. Despite all the shortcomings, the advantages were great. In 140 years, the use of “gonnes” had advanced to the point that the Ottoman Turks were using them to batter down the walls of Constantinople.

There were a whole lot of technical difficulties that had to be attended to before rifling and rifles would have any utility except in a siege. Among them were uniformity of powder, precision measuring systems and mass-production methods. While improvements in firearms technology increased the usefulness of rifles, and insured that rifles would replace shotguns (or “smoothbores” as many prefer) in many applications, improving firearms technology also improved shotguns. In order for rifles to work, the rifling must uniformly engage the bullet the length of the barrel. A rifle barrel must be reamed and polished smooth, straight and even before it can be rifled, or the result will be an inaccurate barrel. The same methods applied to a shotgun barrel produce a more-uniform barrel that delivers consistent groups.

This is a shotgun. Albeit a large shotgun, but a smoothbore none the less. Even when bronze gun tubes had been perfected, being on an artillery crew was dangerous. Early weapons using early gunpowder were not always safe.

The first transition was easy: Going from wooden to metal barrels. Not only did this change the early “bombards” from unwieldy, stationary artillery pieces to marginally mobile ones, metal tubes led to hand-held individual firearms. Well, marginally hand-held, using a monopod with a fork at the top to hold the musket in place. But the race was on.

The powder changes were quick in coming. Early powder was a mixture of the three components, and would settle out during shipping. The gunners would have to re-mix the powder when they got to the battle. “Corned” powder was powder that had been wetted, mixed, dried and re-ground. As you can imagine, grinding black powder into the right consistency is a hazardous profession, but the result was a product that didn't change with storage or shipping, and was much safer and uniform to use.

In the production of gunpowder, quality matters. This is a test gun. A measured charge will propel the spring-marker a known distance if the powder is correctly made.

As late as the Crimean War (1851, The Black Sea, Britain vs. Russia, and the famous poem “Charge of the Light Brigade”) armies still used smoothbore muskets as the general-issue weapon. It was not until a French ordnance officer by the name of Minié developed a hollow-base bullet that expanded on firing that development diverged. Before that brainstorm, the development of firearms was the development of smoothbores, i.e. shotguns. The British Empire was secured, held and lasted long enough to start crumbling during the time of a single model firearm. The “Brown Bess” was a smoothbore flintlock musket whose design was finalized in 1710. The heart of the Brown Bess was the perfected flintlock, a significant advance over competitive systems. The earliest individual smoothbores used the matchlock system. Developed in 1460 in Germany, the matchlock was simple: a pivoted serpentine lever held a clamp at the chamber end. The shooter carried a length of cord that had been soaked in a flammable mixture and then dried. Once ignited, it burned slowly. To fire the loaded smoothbore the shooter would insert one end of the cord (both ends were kept burning, just in case) in the clamp, puffed on it to get it hot, opened the touch-hole cover, and then pointed the “firelock” at the enemy and squeezed the back end of the serpentine. After the matchlock, came the wheellock, snaphaunce and miquelet. The wheellock is the same kind of mechanism as a cigarette lighter. Expensive, fragile and needing a lever to wind it just prior to shooting, the wheellock was not an ideal military weapon. The snaphaunce and miquelet were clumsy precursors to the flintlock, requiring extra parts and fitting.

Early firearms were the weapons and toys of the wealthy. Not only is this snaphaunce elaborately decorated, it is a double-shot single barrel. It was expensive and high-tech for its time.

Despite all the effort that went into developing firearms, the archer was a dominant force on some time. The greatly outnumbered British under Henry V defeated the French at Agincourt in 1415 with accurate longbow shooting. The French knights couldn't advance uphill through the mud faster than the British archers could shoot them down. (One can hardly avoid comparisons 500 years later.) The archer was considered so valuable to national defense that a hundred years later Henry VIII attempted to ban bowling and other sports because they “diverted English men from archery practice.” In rapid fire a skilled archer could launch 10 arrows a minute and place every one of them into a man-sized group more than 100 yards away. At close range an English cloth-yard shaft would go through all but the most heavy and expensive armor. At the same time a matchlock might be fired twice a minute, and guarantee hits only inside 40 yards.

The wheel-lock operates like a spring-driven cigarette lighter. This one is elaborate, expensive, and again, highly decorated.

The Brown Bess could be loaded prior to a battle, and depended upon to fire when needed. It could be quickly (compared to the other style locks) reloaded, and was durable enough to stand up to hard service. With changes in length, and converted to percussion, the same musket was still in use during the Crimean War. Now, 140 years is a long time for any design to hold on, especially a military one. The record may never be broken. After all, do you seriously expect the U.S. armed services to still be issuing M-16s in the year 2105? Even highly-modified ones? (However, I fully expect 1911 pistols to still be in common use, assuming we can still own them, in the year 2051.) Despite the advances in equipment by 1776, Benjamin Franklin still suggested arming revolutionaries with longbows. The drawback was training time. It takes years to train an archer to effectiveness. Granted, a musket was less effective, but the training period was a few weeks.

Until machine production in the 19th century, all firearms parts were made by hand. This early flintlock was made with hand forges and files.

When the musket was used as a military arm, the design had to conform to military needs. The musket was first a “firelock” but primarily a bayonet platform. After the volley, the troops would close the gap with the enemy and fight with bayonets. What they really needed at that point as an instructor was a senior NCO from the Roman Legions, because once the volley was gone, warfare tumbled back 2,000 years. During the Revolutionary War, colonial militias could inflict casualties on the British regulars with accurate rifle and musket fire, but could not keep those regulars from going anywhere they wanted. Even when they loaded their muskets with “buck and ball” (buckshot and a large lead ball) they couldn't keep the British from advancing by gunfire alone.

This wheel-lock is more than 400 years old, and could be loaded and shot today. Quality costs, but it also lasts.

The colonists found their Roman NCO in General Von Steuben, who drilled the tiny army in the tactics and discipline of the day. The next spring, when the newly-trained revolutionary army marched out to meet the British, the commanding officer of the British was heard to remark “Those are regulars, by God.”

The rifled musket changed that. With the speed of fire of the musket, and the accuracy of a rifle, units could no longer maneuver in the open, and close the distance for a bayonet charge with impunity. Unfortunately, it took several more wars for the knowledge to become common. Companies and battalions that tried to do so in the Civil War found themselves taking horrendous casualties before they could close the distance. Military needs and desires went to the rifle, and left the shotgun for a while. Freed from the need to be a bayonet lever, shotguns began to get lighter, more responsive and better suited to hunting. The ethos of taking game only on the move, birds in flight and small game while running, took hold. The British in the next half-century turned the shotgun into an extension of the shooters arm. Well, the extension of a shooter who could afford to have a shotgun tailored to him as if it were merely one more accessory to his clothing.

The French Military Museum houses a fine collection of black-powder martial weapons and the Tomb of Napoleon. The tomb is even gaudier than some of the weapons on display.

The British shotgun grew out of the double-barreled muzzle-loader. When shotguns were still muzzle-loaders, the easiest way to have a second shot readily available was to have a second, loaded shotgun. To build two barrels on one gun took skill, or the result was so heavy as to be unusable. British hunting was (and is) primarily driven-game hunting. The Gentlemen hunters wait by their shooting stands as the game is driven towards them, and then shoot it as it attempts to flee past. The shooting is fast, and the game is almost always going straight overhead, or past on the sides. With each development in firearms technology, the British gun-makers made the “double” lighter, handier, more responsive, more reliable and more decorated. They finally created a 12-gauge shotgun that weighs less than 6 pounds, is utterly reliable, hits where you look (provided it has been fitted to you) and costs more than a car. If you can afford the tens of thousands of dollars such a shotgun costs, then you have your choice of engraving style, amount of coverage, wood selection and chokes. You can have an extra set of barrels fitted, starting at several thousand dollars and going up. But you have to be patient, as the gunsmiths who build such wonders are booked solid for years in advance.

These spectacular shotguns are notable not only for the gold inlay in the barrel and ribs, but the number of shots. Each is a four-barreled gun, with two locks top and bottom.

The American path was and still is different. Right in the middle of the cartridge conversion process for shotguns, in the 1890s, John Browning kept insisting on a different idea: The repeating shotgun. At first Winchester insisted on a lever-action shotgun. I'm sure John wasn't too keen on the idea, but they were offering him money for a lever shotgun, so he did his best. Awkward, fragile, clumsy to use and borderline homely, the Winchester lever shotguns didn't catch on. It didn't help that Browning designed the Model 1893, and then updated it with the 1897. The '97 is a pump. Without the need for the linkages and elbow room a lever needs, the receiver of the '97 was sleek and compact. No shotgun is truly durable. The wall thicknesses of the barrel and magazine are not enough to stand up to abuse, but the '97 was much more durable than was a doublegun. For someone depending on a shotgun to feed his family, the '97 was much more attractive than any double. For a Sheriff on the Western frontier, dealing with dangerous men was a thankless task. When faced with more than one, a double might not be enough extra insurance. Faced with a resolute sheriff holding a Winchester pump and its seven rounds of buckshot, even the most hardened desperado might think twice.

Once American hunters took to the pump, every manufacturer had to make at least one, and within a couple of decades doubles were on the wane. One place doubles hung on for a long time was at the gun club. Early competitions (mid to late 19th century) were live-bird contests. Each bird was released from a trap in the middle of a circle. Each contestant had to shoot the bird and drop it within the circle. Even if killed, if the bird fell outside of the circle the competitor was said to have “lost” it. (What can I say, times were different then.) The competitor was only allowed two shots at each bird, so doubles worked just fine. And, no gentleman would be caught on the club grounds with a repeater. It was the hunting gun of the working classes! (Of course, the fact that early live-pigeon shoots were deemed to be diversions for the lower classes, and occasions for vigorous gambling, were quickly overlooked when gentlemen decided to take up the sport.) The difficulty of obtaining birds and the irregularity with which they flew led competitors to other targets. An early target was glass balls. The throwing mechanism was a spring arm that threw the balls straight up. A later and less expensive target is the “clay pigon” that we all know. Its disk shape required a different throwing mechanism, and threw the bird out rather than up. By angling the throwing arm, the bird could be thrown up and away from the shooter. The game of trap shooting had been invented. Later, skeet was invented as a target game that more closely simulated the various angles with which hunters were faced. After all, if you spent the whole summer practicing on trap with its upwards and going-away targets, how does that help you when in the fall a flight of ducks is attempting to land on the pond in front of you, coming straight at you and going down?

Some military requirements haven't changed since the time of Caesar. When the United States went to fight in France in World War I, the shotguns had to have a bayonet adapter.

If the pressure for quality and reliable guns wasn't enough, the interest in the sporting applications of shotguns put more pressure on gunmakers. In short order, the best makers were turning out beautifully balanced shotguns of unparalleled reliability. And for those who could afford them, great beauty.

Just when it seemed that the shotgun would disappear from the military equipment lists, America entered The War to End All Wars. General Pershing quickly determined that shotguns would be of great use in the trenches of World War I, and the U.S. Army has had shotguns of various types in service ever since.

By the end of the 20th century, some would say that shotguns had gotten back to being bayonet levers. Faced with the requirement to use steel shot, longer shooting distances, and harder-to-get-to hunting locations, hunters have upgraded. Back when Eisenhower was President, a duck hunter might have a double or a pump that weighed 8 pounds. It would be loaded with an ounce and a quarter of No. 4 lead shot, and choked improved cylinder or modified. The shells probably weren't magnums, and he would be well-armed for the task.

Now, a hunter who doesn't go out with a shotgun chambered for a 3-½-inch 12-gauge shell, or even a 10-gauge, that weighs almost 10 pounds (to deal with the recoil on those magnums, oh, brother) throwing a payload of 1-½ ounces of BB's, feels undergunned. And he will be camouflaged to the gills, with a pocket full of screw-in choke tubes to deal with any potential problem. The modern duck and goose gun can be as long and heavy as the old Brown Bess musket. But without the bayonet. Even the newest duck hunter doesn't think he will have to repel web-footed boarders.

For night raids and trench clearing, there wasn't much better in 1917 than a Winchester pump. This shotgun must have been great comfort to a Doughboy in No Man's Land.