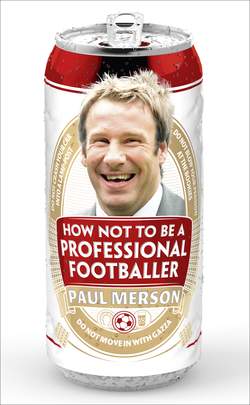

Читать книгу How Not to Be a Professional Footballer - Paul Merson - Страница 6

ОглавлениеLesson 1

Do Not Go to Stringfellows with Charlie Nicholas

‘Where Merse lays the first bet, reads his rehab diary and gets a taste of the playboy lifestyle.’

It was the beginning of the end: my first blow-out as a big-time gambler. There I was, a 16-year-old kid on the YTS scheme at Arsenal with a cheque for £100 in my hand – a whole oner, all mine. That probably sounds like peanuts for a footballer with a top-flight club today, but in 1984 this was a full month’s pay for me and I’d never seen that amount of money in my life, not all at once anyway. Mate, I thought I’d hit the Big Time.

It was the last Friday of the month. I’d just finished training and done all the usual chores that you have to do when you’re a kid at a big football club, like cleaning the baths and toilets at Highbury and sweeping out the dressing-rooms for the first-team game the next day. When that was done, Pat Rice, the youth team coach, came round and gave all the kids a little brown envelope. Our first payslips were inside, and I couldn’t wait to draw my wages out. I got changed out of my tracksuit and ran down the road to Barclays Bank in Finsbury Park with my mate, Wes Reid. I swear I was shaking as the girl behind the counter passed over the notes.

‘What are you doing now, Wes?’ I asked, as we both counted out the crisp fivers and tenners. I was bouncing around like a little kid.

‘I’m going across the road to William Hill,’ he said. ‘Fancy it?’

That’s where it all went fucking wrong. I’d never been in a bookies before, but I was never one to turn down a bit of mischief. I wish I’d known then what I know now, because Wes’s offer was the moment where it all went pear for me. The next 15 minutes would blow up the rest of my life, like a match to a stick of dynamite.

‘Yeah, why not?’ I said.

It was the wrong answer, and I could have easily said no because it wasn’t like Wes was pushy or anything. In next to no time, I’d blown my whole monthly pay on the horses and my oner was down the toilet. I think I did my money in 15 minutes, I’m not sure. I’d never had a bet in my life before. It’s a right blur when I think about it. I left the shop in a daze. Moments earlier I’d been Billy Big Time, but in a flash I was brassic. All I could think was, ‘What the fuck have I done?’

At first I felt sick about the money, I wanted to cry, and then I realised Mum and Dad would kill me for spunking the cash. As I walked down the high street, I promised myself it would never happen again. I also reckoned I could talk my way out of trouble when Mum started asking all the questions she was definitely going to ask, like:

‘Why are you asking for lunch money when you’ve just been paid?’

‘Why can’t you afford to go out with your mates?’

‘What have you done with that hundred quid Arsenal gave you?’

At that time, Mum was getting £140 from the club for putting me up at home, which was technically digs. She’d want to know why I was mysteriously skint, or not blowing my money on Madness records or Fred Perry jumpers. There was no way I was going to tell her that I’d handed it all to a bookie, she would have gone mental. As I got nearer to Northolt, where we lived, I worked out a fail-safe porkie: I was going to make out I’d been mugged on the train.

Arsenal had given me a travel pass, which meant I could get back to our council-estate house no problem. The only hitch was my face. I looked as fresh as a daisy – there were no bruises or cuts. Mum wasn’t going to believe I’d been given a kicking by some burly blokes, so as I got around the corner from home, I sneaked down a little alleyway and smashed my face against the wall. The stone cut up my skin and grazed my cheeks, and I was bleeding as I ran through our front door, laying it on thick about some big geezers, a fight and the stolen money. They fell for it, what with my face being in a right state, and I was off the hook.

Nobody asked any questions as Dad patched up the scratches and cuts, and the police were never called. Later, Mum gave me the £140 paid to her by Arsenal. I thought I’d been a genius. My quick thinking had led to a proper result, but I couldn’t have guessed that it was the first lie in a million, each one covering up my growing betting habit.

As I went to sleep that night, I told myself another lie, almost as quickly as I’d told the first.

‘Never again, mate,’ I said. ‘Never again.’

Ten years after the bookies in Finsbury Park, I went into rehab at the Marchwood Priory Hospital in Southampton. Booze, coke and gambling had all beaten me up, one by one. I never did anything by halves, least of all chasing a buzz, but I was on my knees at the age of 26. That first flutter had started a gambling addiction I still carry today.

As part of the treatment, doctors asked me to write a childhood autobiography as I sat in my room. I think it was supposed to take me back to a time before the addictions kicked in, to help get my head straight. I’ve still got the notes at home, written out on sheets of lined A4 paper. When I read those pages now, it seems my only real addiction as a lad was football, and that made me sick, too.

I was such a nervous kid that I used to wet the bed. I had a speech impediment, which meant I couldn’t pronounce my S‘s, and I had to go through special tuition to sort it out. When I started playing football I’d get so anxious that I’d freak out in the middle of school games. God knows where it came from, but I used to get palpitations during Sunday League matches and I couldn‘t breathe. My heart would pound at a million miles an hour, and the manager would have to sub me because I thought I was dying. Mum and Dad took me to our local GP for help, and once I realised the pounding heart and breathing problems were only panic attacks and that they passed pretty quickly, I calmed down a bit.

I was a good schoolboy player, turning out for Brent Schools District Under-11s even though I was a year younger than everyone else. When I was 14, I was spotted playing for my Sunday morning side, Kingsbury’s Forest United, and scouts from Arsenal, Chelsea, QPR and Watford wanted me to train with them. I went down to Watford, where I saw Kenny Jackett and Nigel Callaghan play (they were Watford players, if you hadn’t sussed), and I went to Arsenal as well. I thought I’d have more of a chance of making it at Watford because of my size – I figured a small lad like me would have more hope of getting into the first team there – but my dad was an Arsenal fan, so I did it for him. In April 1982, I signed at Highbury on associated schoolboy forms, which meant I couldn’t sign for anyone else until I was 16.

The chances of me becoming a pro were pretty slim, though. I had the skills for sure, I was sharp, quick-witted and I scored a lot of goals as a youth team player, but I was double skinny and Arsenal’s coaches were worried that I might not be big enough to make it as a striker in the First Division. I definitely wasn’t brave. When I played in games, I was terrified of my own shadow. It only needed a big, ugly centre-half to give me a whack in the first five minutes of a match for me to think, ‘Ooh, don’t do that, thank you very much,’ and I’d disappear for the rest of the game, bottling the fifty-fifty tackles.

Don Howe was the manager at Highbury, and he was pushing me about too, but it was for the best. He’d spotted the flaws in my game and wanted me to toughen up. In 1984 he called me into his office, took a look at my bony, tiny frame and said, ‘I’m not making you an apprentice, son, but I am going to put you on the YTS scheme. We get one YTS place from the government, so I have to take a gamble and I’m taking the gamble on you.’

There was a hitch, though. ‘If you don’t get any bigger, we won’t be signing you as a professional,’ he said, looking proper serious.

I didn’t care, I was made up. I prayed to God that I’d fill out. I stuffed my face with food and pumped weights during the week like a mini Rocky Balboa.

In a way, getting a YTS place was like Charlie finding the golden ticket to Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory, because it was a bit of a lottery really. Any one of a dozen kids at the club could have got that spot, but they gave it to me. The YTS players in Division One were also a bonus ball for the youth system. The government paid my wages (that oner a month), so it wasn’t like the club had to fork out any cash for me. In the meantime, I was playing football and handing cash back to Maggie Thatcher in gambling taxes. Happy days all round.

But I still moaned. Being a YTS or apprentice player was a pain in the arse at times and I had to travel across London from Northolt to Highbury. Every morning without fail I’d get on the underground for 16 stops to Holborn, then I’d change to the Piccadilly Line and go the last stretch to the club. I lost count of the times I had to get off at Marble Arch to go to the loo. I had to run up the escalators of the station, nip into the khazi at McDonalds and then run back for another train.

Once I got to the ground, I’d help the other apprentices put the kit on the coach. We’d then drive 50 minutes into the countryside, train for a couple of hours and come back home again. I was constantly knackered. On the way home I’d always fall asleep on the tube. Luckily for me, Northolt was only a few stops from the end of the Central Line, so if I fell akip and woke up in West Ruislip, I didn’t have far to travel back.

It didn’t get much better for me when it came to playing football either. Because of my size I was never getting picked for the team and I was always sub. Sometimes I even had to run the line. During a pre-season game against Man United I was lino for the whole match and I had the hump, big-time. It didn’t help that my mates were getting £150 a week for working on a building site when I was only get £25.

My attitude was bad. I kept thinking, ‘I ain’t going to make it as a footballer. I’m not even playing now. What chance have I got?’ At that point I would have strolled over to the nearest construction foreman and said, ‘Give us a job’, but my dad kept saying the same thing to me again and again: ‘Keep on going.’ The truth is, I could have packed it in 50 times over.

Arsenal weren’t much of a team to look at then. When I watched them play at Highbury, which the kids had to every other Saturday, they weren’t very good. They had some great players around like Pat Jennings in goal, plus internationals like Viv Anderson, Kenny Sansom, Paul Mariner, Graham Rix and Charlie Nicholas, but Don couldn’t get them going. They were getting beat left, right and centre and the fans weren’t interested. These days, Arsenal tickets are as rare as rocking horse shit. In 1985, that team was playing in front of crowds of only 18,000.

At the same time, I started getting physically bigger and tougher in the tackles, which was a shock for everyone because my mum and dad were small. Suddenly I could look over the heads of the other fans on the North Bank. In matches I started being able to read the game, and I became what the coaches would call ‘intelligent’ on the pitch. Off it I was a nightmare, but when I was playing I was able to see the game unfolding in front of me. I could picture where players would be running and where chances would be coming from next, which a lot of other footballers didn’t. And I was lucky, very lucky, because I didn’t get injured.

See, this is the thing that people don’t tell kids about professional football: it’s so much down to luck, it’s scary. If you don’t play well in that first district game, the scout from QPR or Charlton isn’t coming back. If you get injured in your first youth team match at Wolves and miss seven months of action, chances are, you’re not getting signed. I was lucky because I avoided the serious knocks. My only bad injury came when I ripped my knee open on a piece of metal when I was 12 years old (before I’d joined Arsenal), and that now seems like a massive stroke of luck when I think about it.

I was playing football with my mates on some park land at the back of our house in Northolt. I was stuck in goal and as a ball came across I rushed out for it, quick as you like, sliding across the turf. The council were still building around the estate then, and there was rubble and crap everywhere. A piece of metal wire sticking in the ground snagged the skin on my knee and tore it right down to the bone.

It was touch and go whether I’d play football again. The doctors gave me a Robocop knee with 30 stitches on the inside, another 30 on the outside. With medical science, they pieced me together with catgut, the wire they used in John McEnroe’s tennis rackets. It gave my right leg some kind of super strength. After that I never had to use my left peg, because I could kick the ball so well with the outside of my right thanks to the extra support in my knee. When I was at Villa, our French winger David Ginola said to me, ‘You are zee best I ‘av ever seen at kicking with the outside of your foot, Merz.’ That’s some compliment coming from a great player like David, I can tell you.

As a trainee at Arsenal, I had the odd twisted ankle, a few bruises, but that was it. And then things started happening for me in the youth team. It took about seven months, but as I got bigger I became a regular in the starting line-up. I was scoring goals and playing well, while the lads in the year above me, like Michael Thomas, David Rocastle, Martin Hayes and Tony Adams, started playing in the reserves, knocking on the first-team door. I was offered a second year on my YTS contract and began training with the first team shortly afterwards. It was Big Boy stuff, but I really fancied my chances of getting a proper game. I even dreamt of watching myself on Match of the Day.

Then I made it into the reserve team. Once a youth footballer gets to that stage in his career, it can get pretty brutal. The pressure is really on to get a pro contract. Players are often chasing a place in the first-team squad with another apprentice, someone who could be their best mate. I spent a lot of time worrying whether I was going to make it or not, and it got to me. The panic attacks came back. During a reserve game against Chelsea I latched on to a through ball and rounded their keeper Peter Bonetti, who I’d loved as a kid because I was a Chelsea fan (though Ray Wilkins was my idol). But as I was about to poke it home, I got the fear and froze like a training cone. A defender nicked the ball off me and I was left there, looking like a right wally, feeling sick. A few days later I went to the doctors again, but the GP was like a fish up a tree. He told me to give up football, but I wasn’t going to do that. I loved the game too much.

At training I managed to hold it together, which was a relief because I was playing with some proper superstars. Charlie Nicholas was one of them and he was a god to the Arsenal fans. He’d come down from Celtic, where he’d smashed every goalscoring record going. Graham Rix was there too, as was Tony Woodcock and top England centre-forward Paul Mariner, who was a player and a half. It was a massive deal for me. I remember being on the training ground and thinking, ‘My God, these people are legends.’

The biggest shock was that they were all so normal. None of them were big-time, none of them were Jack-the-lads. It was a help, because I was a normal bloke too. I was determined never to become a flash Harry, which was probably what got me into trouble in the long run, and I could never say no to my mates at home. I’d already smoked weed in the park with them, but I’d packed it in when I signed Don Howe’s YTS contract. I liked it because it relaxed me, but it gave me the munchies. I’d always end the night at the counter of a 24-hour petrol station buying bars of chocolate and packets of crisps, which wasn’t the best for someone with an ambition to make it in the First Division.

I also liked a drink, which was something I was better suited to than grass. I found that the more I drank, the fewer panic attacks I’d have. I started in my early teens, knocking back the Pernod and black with mates, which was always colourful when it came back up. It didn’t put me off, though. If my mum and dad went out on a Saturday night they’d often come back and find me passed out on the sofa, surrounded by a dozen empty cans of lager.

I suppose it was good training. After I’d been working with the first team for a while, Charlie Nicholas and Graham Rix took me under their wing, but this time it was off the pitch as well as on it. They had showed me the ropes at the club and told me how to handle myself during games, and then they invited me to Stringfellows in London, a fancy footballers’ hang-out in the West End. My eyes were on stalks when I walked in for the first time, there were birds everywhere and they all wanted to meet Charlie. He had the long hair, the earring and the leather trousers. He was a football superstar, like George Best had been in the seventies.

‘Fuck, I like this,’ I thought. ‘I want to be like him.’

This was at a time long before Stringfellows became a strip club, but it might as well have been one. The girls were wearing next to nothing and there were bottles of bubbly everywhere. Tears for Fears and Howard Jones blasted out from the speakers. I looked like the character Garth from Wayne’s World because my eyes kept locking on to every passing set of pins like heat-seeking radar, and I couldn’t believe the amount of booze that was flying around. Graham Rix’s bar bill would have put my gambling binge with Wes to shame.

I crashed round at Charlie’s house afterwards, a fancy apartment in Highgate with an open-plan living-room and kitchen, plush furniture, the works. I wanted all of it. Luckily, the club had decided to sign me as a pro, and I couldn’t scribble my name down quick enough because there was nothing more I wanted in the world than to be a professional footballer. And I fancied another night in Stringfellows.

I got my contract on 1 December 1985 and at the time I thought it was big bucks, all £150 of it a week. Oh my God, I thought I’d made it, even though I was earning the same amount of dough as my mates on the building site. That didn’t stop me from celebrating. I remember going round to my girlfriend Lorraine’s house with a bottle of Moët because I reckoned I was on top of the world. The first-team players had given me a sniff of the high life available to a top-drawer footballer, and how could I not be sucked in by the glamour? I’d tasted bubbles with Champagne Charlie before we’d shared half-time oranges.

Arsenal were having a ’mare in 1986. Don resigned after a lorryload of shocking results, and George Graham turned up in May. I was gutted for Don. He was a top coach, one of the best in the world at the time. I worked with him again when he was looking after the England Under-19s, and he was phenomenal, really thorough and full of ideas. When he talked, you listened, but Don’s problem was that he didn’t have it in him to be a manager. Really, he was just too nice.

As a coach he was perfect, a good cop to a manager’s bad cop. If a manager had bollocked the team and torn a strip off someone, I imagine Don would have put his arm around them afterwards. He would have got their head straight.

‘Now don’t you worry about it, son,’ he’d say. ‘The gaffer doesn’t really think you’re a useless, lazy fuckwit, he just reckons you should track back a bit more.’

Being a coach and a manager are two very different jobs. When someone’s a coach they take the lads training, but they don’t have the added pressure of picking the team or running the side, and that makes a massive difference. I don’t think Don could hack that. He wasn’t the only one, there have been loads of great, great coaches who couldn’t do it as a manager. Brian Kidd was a good example. He was figured to be one of the best coaches in the game when he worked alongside Fergie at United. He went to Blackburn as gaffer and took them down.

Our new manager, George Graham, was a mystery to me. I didn’t know him from Adam, apart from the fact that he was an Arsenal boy and he wanted to rule the club in a strict style. I’d heard he’d been a bit casual as a player. Some of the lads reckoned he liked a drink back in the day, and they used to call him Stroller at the club because he seemed so relaxed when he played, but when he turned up at training for the first time he seemed a bit tough to me. Straightaway, George packed me off to Brentford because he thought some first-team football with a lower league club would do me good. Frank McLintock, his old Arsenal mate, was in charge there and George was right, it did help, but only because we got so plastered on the coach journey from away games that some of the players would fall into the club car park when we finally arrived home. It prepared me for a lifetime of boozing.

I signed with Brentford on a Friday afternoon. Twenty-four hours later we played Port Vale, and what an eye-opener that was. To prepare for the game, striker Francis Joseph sat at the back of the bus, smoking a fag. We were comfortably beaten that afternoon and Frank McLintock was sacked on the coach on the way back. I thought, ‘Nice one, the fella who’s signed me has just been given the boot.’ I couldn’t believe it.

After that, though, it was plain sailing. Former Spurs captain Steve Perryman took over the club as player-manager and got us going. We didn’t lose again, and after every game we celebrated hard. I remember we played away at Bolton in a midweek match, and when we got back to the dressing-room at 9.15, a couple of the lads didn’t even get into the baths. They changed and ran out of the dressing-room so they could get to the off-licence before it closed. On the way home we all piled into a couple of crates of lager and got paro. It was a different way of life than at Arsenal. I learnt at Highbury that you could have a drink on the way home, but only if you’d done the business. At Brentford you could have a drink on the way home even if you hadn’t played well.

Going to Brentford back then was probably the best thing that could have happened to me, because it made me appreciate Highbury even more. By looking at Brent-ford I could see that Arsenal was a phenomenal club. The marble halls at Highbury, the atmosphere, the way they looked after you was top, top class. I went everywhere in the world with them during my career. We played football in Malaysia, Miami, Australia and Singapore. When we played in South Africa a few years later, we were presented with a guest of honour before the match, a little black fella with grey hair. When he shook my hand, I nudged our full-back, Nigel Winterburn, who was standing next to me.

‘Who the fuck’s that?’ I said.

Nige couldn’t believe it.

‘Bloody hell, Merse, it’s Nelson Mandela,’ he said. ‘One of the most famous people in the world.’

I’m not being horrible, but I never got that treatment at Aston Villa. They were a big club and we might have gone to Scandinavia for a pre-season tour, or played in the Intertoto Cup, but it was hardly South Africa and a handshake from Nelson Mandela. I never got that at Boro or Pompey either, and I definitely didn’t get that at Brent-ford. A couple of days after the Port Vale game, following my first day training there, I went into the dressing-rooms for a shower and chucked my kit on the floor. Steve Perry-man picked it up and chucked it back at me.

‘What are you doing?’ he said. ‘You’ve got to take that home and wash it.’

I couldn’t believe it. At Arsenal, one of the kids would have done that for me. I’d train, get changed and the next day my kit would be back at the same place in the dressing-room, washed, ironed, folded up and smelling as fresh as Interflora, even though I didn’t have a first-team game under my belt.

I loved it at Brentford and I was so grateful to them for starting my career. I go and watch them whenever I can, but I wasn’t there for long as George soon called me back. Steve had wanted to keep me for a few more months, but I knew that getting recalled to Highbury so quickly meant one thing only. It was debut time.

I was right as well. I made my first appearance against Man City at home on 22 November 1986, coming on as a sub in a 3–0 win. I ran on to the pitch and all the fans were cheering and singing for me. Then with my first touch, a shocker, I put the ball into the North Bank. It was supposed to be a cross. Instead it went into Row Z. The Arsenal fans must have thought, ‘What the fuck have we got here? This guy looks like a right Charlie.’ They didn’t know the half of it.