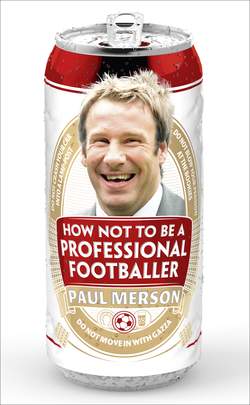

Читать книгу How Not to Be a Professional Footballer - Paul Merson - Страница 7

ОглавлениеLesson 2

Do Not Drink 15 Pints and Crash Your Car into a Lamppost

‘Our teenage sensation drinks himself silly and gets arrested. Tony Adams wets the Merson sofa bed.’

That’s when the boozing really started. Under George, I got to the fringes of the first team at the tail end of the 1986–87 season, and whenever I played at Highbury I’d always go into an Irish boozer around the corner from the ground afterwards. The Bank of Friendship it was called. In those days, my drinking partner was Niall Quinn, who had signed for the club a few years earlier. If you had said to me then when I was 17 or 18, ‘Oh, Niall’s going to be the chairman of Sunderland when he’s 40-odd,’ I’d have thought you were having a laugh. He wasn’t that sort of bloke.

We’d often play games in the stiffs together, which took place in midweek. On the day of a match, we’d spend hours in the bookies before heading back to Niall’s place for a spicy pizza, which was our regular pre-match meal. His house was a bomb site. I’d regularly walk into his living room and see six or seven blokes lying on the floor in sleeping bags.

‘Who the fuck are these, Quinny?’ I’d ask.

‘Oh, I dunno. Just some lads who came over last night from Ireland.’

It was hardly chairman of the board material.

My Arsenal career had started with a few first-team games here, some second-string games there, but word was starting to spread about me. My life in the limelight had begun a season earlier in the 1985 Guinness Six-aSide tournament, which was a midweek event in Manchester for the First Division’s reserve team players and one or two promising kids. I loved it because the highlights were being shown on the telly.

We lost in the final but I was in form and picked up blinding reviews whenever I played. I was performing so well that the TV commentator Tony Gubba started banging on about me, saying I was a great prospect. Then Charlie Nicholas did a newspaper interview and claimed I was going to be the next Ian Rush. Suddenly the Arsenal fans were thinking, ‘This kid must be good.’ Everyone else wanted to know what all the fuss was about.

The only person who wasn’t getting carried away was George. After my debut against City I had to wait until April 1987 before my first full game, and that was a baptism of fire because it was an away game against Wimbledon, or The Crazy Gang as most people liked to call them, they were that loony. In those days they intimidated teams at Plough Lane, their home ground. The dressing-rooms were pokey, and they’d play tricks like swapping the salt for sugar, or leaving logs in the loos, which never flushed properly. It annoyed the big teams like Arsenal who were used to luxury. Then they’d make sure the central heating was on full blast in the away room; that way the opposition always felt knackered before kick-off.

They were pretty hard on the pitch too. Vinnie Jones was their name player then, but Dennis Wise and John Fashanu could cause some damage. To be fair, they sometimes played a bit of football if they fancied it, but that day we won 2–1 in an eventful game. Vinnie got sent off for smashing into Graham Rix, and I scored my first goal for Arsenal, a header. As it was going in, their midfielder Lawrie Sanchez tried to punch it away, but he only managed to push it into the top corner. I thought, ‘The fucking cheek.’

I played in another four games as George eased me into the swing of things, but nobody else was handling me with kid gloves. In the next match I played against Man City again, this time at Maine Road, and when we kicked off I ran to the halfway line. I was watching the ball at the other end when City’s centre-half, Mick McCarthy, smashed me right across the face. He didn’t apologise but instead gave me a look that said, ‘You come fucking near me again and I’ll snap you in half.’

‘No chance of that,’ I thought. I hardly touched the ball afterwards.

George changed everything at Arsenal. In his first season, we won the 1986–87 Littlewoods Cup Final, beating Liverpool, 2–1, though I wasn’t involved in the game. At Wembley, Charlie scored both goals, but because he was a bit of a player in the nightclubs, George didn’t want him around. Three games into the 1987–88 season he was dropped and never played again. George later sold him. I was gutted when I heard the news, because he was such a top bloke to be around. I never saw him turn up for training with the hump. Even when things weren’t going well, or the goals weren’t going in, he always had a smile on his face.

He wasn’t the only one to be shown the door. George could see a lot of the lads were going out on the town, and they weren’t winning anything big, so he decided to make some serious changes. During the 1987–88 season players like David ‘Rocky’ Rocastle, Michael ‘Mickey’ Thomas, Tony Adams and Martin Hayes started to make the first team regularly. I was getting a lot of games too, featuring 17 times and scoring five goals, though over half those appearances came as sub.

Looking back, it was obvious what George was doing. He wanted to be around young players who could be bossed about. He wanted to put his authority on the team. Seasoned pros like Charlie wouldn’t have fallen in line with his ideas, not in the same way as a bunch of wet-behind-the-ears kids.

Full-backs Nigel Winterburn of Wimbledon and Stoke’s Lee Dixon joined the club and were followed in June 1988 by centre-half Steve Bould. Apparently, Lee had been at about 30 clubs, but I’d never heard of him before. The team transformation didn’t end with the defence. He also signed striker Alan ‘Smudger’ Smith from Leicester City. All of a sudden we were a really exciting, young side and everyone was thinking, ‘Bloody hell, this could work.’

We only finished sixth in the League in 1987–88, but the new Arsenal were starting to glue. Rocky, God bless him, was one of the best wingers of his generation. He had everything. He could pass the ball, score goals and take people on. But he was also hard as nails and could really put in a tackle. At the same time he was one of the nicest blokes ever and nobody ever said a bad word about him, which in football was a massive compliment. What a player – he should have played a million times for England and he was Arsenal through and through. When George sold him to Leeds in 1992, he was devastated, it broke his heart. It broke our hearts when he died of cancer in 2001.

We used to call Mickey Thomas ‘Pebbles’, after the gargling baby in The Flintstones, because you could never understand what he was saying, he always mumbled, but he was an unbelievable player. When it came to training, George rarely let us have five-a-side games, maybe on a Friday if we were lucky. When we did play them, he always sent Mickey inside to get changed. Because he was such a good footballer, Mickey would always take the piss out of the rest of us, and George wasn’t having that. Everything had to be done seriously, or there was no point in doing it at all.

Centre-half Steve Bould was the best addition to the first-team squad as far as I was concerned, because along with midfielder Perry Groves, who was signed from Colchester in 1986, he became one of my drinking partners at the club. His main talent, apart from being a professional footballer, was eating. Bloody hell, he could put it away. On the way home from away games, there was always a fancy table service on the coach, complete with two waiters. The squad would have a prawn cocktail to start, or maybe some salmon or a soup. Then there was a choice of a roast dinner or pasta for the main course, with an apple pie as dessert. That was followed up with cheese and biscuits. In the meantime, the team would get stuck into the lagers. If we’d won, I’d always grab a couple of crates from the players’ lounge on the way out.

Bouldy was six foot four and I swear he was hollow. We’d have eating competitions to kill time on the journey and he would win every time. Prawn cocktails, soup, salmon, roast chicken, lasagnes, apple pies, cheese and biscuits – he’d eat the whole menu and then some. Everything was washed down with can after can of lager. By the time the coach pulled into the training ground car park, we’d fall off it. I’d have to call my missus for a lift because I couldn’t drive home, but Bouldy always seemed as fresh as a daisy as he made the journey back to his gaff. He probably stopped for a curry on the way.

George worked us hard, really hard, and training was a nightmare. On Monday, we’d run in the countryside. On Tuesday, we’d run all morning at Highbury until we were sick. We’d do old-school exercises, like sprinting up and down the terraces and giving piggybacks along the North Bank. Modern-day players wouldn’t stand for it, they’d be crying to their agents every day, but George could get away with it because we were young and keen and not earning huge amounts of money. We didn’t have any power.

Still, it was like Groundhog Day and I could have told you, to the drill, what I was doing every single day of the week for the first three months of the 1988-89 season. Most of it was based on the defensive side of the game, George was obsessed by it. We would carry out drills where two teams had to keep possession for as long as possible, then we’d work with eight players keeping the ball against two runners.

In another session, George would set up a back six of John Lukic in goal, Lee Dixon and Nigel Winterburn as full-backs, and Tony and Bouldy as centre-halves, with David O’Leary protecting them in the midfield. A team of 11 players would then try to break them down. They were phenomenal defensively. If we scored more than one goal against them in training, we knew we’d done well. Sometimes George would link the back four with a rope, so when they ran out to catch a striker offside, they would get used to coming out together, arms in the air, shouting at the lino. It wasn’t a fluke that clean sheets were common for us in those days, because George worked so hard to achieve them.

We did the same thing every day, but the lads never moaned. If anyone grumbled they were soon dropped for the next match, and so we worked every morning on not conceding goals without a murmur. Everyone listened to George, because we were all frightened of what he would do if we didn’t live up to his high standards. He was nothing like the laid-back player everyone had heard about.

As a tactician he was brilliant, and his knowledge was scary, but he was even scarier as a bloke. If you didn’t do what he’d said, like getting the ball beyond the first man at a corner, he’d bollock you badly. When George walked into a room, everybody stopped talking, and nobody ever dared to challenge him if they thought what he was doing was wrong or out of order.

Our defender (or defensive midfielder, depending on the line-up) Martin Keown was the only person to have a go at George in all the time I was there. I remember we went to Ipswich and had a nightmare. God knows why the argument started, but it ended up with Martin shouting at George in the dressing-room – giving it, trying to start a ruck.

‘Come on, George!’ he yelled as the lads stared, open-mouthed. ‘Come on!’ He didn’t play for ages after that.

Fans wondered why George didn’t stay around the game much longer than he did, but it’s pretty obvious really – the players wouldn’t stand for his methods of management today. They earn too much money, they wouldn’t have to listen to him. They’d be moaning in the papers and asking for a move as soon as he’d got them giving piggybacks in training.

Wednesdays were great because George always gave the squad a day off. That meant I could get hammered on a Tuesday night, which I did every week. Often I was joined by some of the other lads, like Steve Bould, Tony Adams, Nigel Winterburn and Perry Groves. We’d start off in a local pub, then we’d go into London and drink all over town. We wouldn’t stop until we were paro. The pint-o-meter usually came in at 15 beers plus and we used to call our sessions ‘The Tuesday Club’. George knew about the heavy nights, but I don’t think he cared because we were always right as rain when we arrived for training on Thursday.

Bouldy was always up for a drink in those days, as was Grovesy, but he was a bit lighter than the rest of us. Sometimes he’d even throw his lagers away if he thought we weren’t looking. I remember the night of Grovesy’s first Tuesday Club meeting. It took place during his first week at the club, and we went to a boozer near Highbury. He stood by a big plant as we started sinking the pints, and when we weren’t looking he’d tip his drink into the pot. Grovesy threw away so much beer that by the end of the evening the plant was trying to kiss him. When we went back to training on Thursday, everyone was going on about what a big drinker he was, because he’d been the last man standing.

The following week we went into the same pub and one of the lads stood next to the plant. I think they’d worked out that Grovesy wasn’t the big hitter we’d thought he’d been, and he was right. After three drinks, Grovesey was paro and couldn’t walk. As he staggered around the pub an hour later, he confessed that he’d been chucking his drinks because he was a lightweight. That tag didn’t last long, though. After one season, he’d learnt how to keep up with the rest of us. He joined Arsenal a teetotaller and left a serious drinker.

It wasn’t just Tuesday nights that we’d go for it – I’d take any excuse for a piss-up. My problem came from the fact that I used booze to put my head right, to calm me down or perk me up. When I was a YTS player, drinking stopped the panic attacks, but when I started breaking into the first team, beer maintained the excitement of playing in front of thousands of Arsenal fans.

It’s a massive buzz playing football, especially when everything is new, like when I got my first touches against Man City at Highbury, or that goal at Plough Lane. The adrenaline that came with playing on a Saturday gave me such a rush. And if I scored, it was the best feeling in the world, nothing else came close. The problems started when I realised the buzz was short. I felt flat when I left the pitch, and I’d sit in the dressing-room after a game, thinking, ‘What am I going to do now? I can’t wait until next Saturday.’ And that’s where the drinking came in. It kept my high up.

I should have known better, because before I’d made it into the first team regularly, boozing had already got me into trouble. When I was 18, I got done for drink-driving. It was in the summer of 1986, I went to a place called Wheathampstead with a few people and we rounded the night off in the Rose and Crown, a lovely little boozer near my house. After a lorryload of pints, I decided to drive home, pissed out of my face, though I must have crashed into every other car outside the pub as I reversed from my parking spot. I missed the turning for my house, went into the next road and ploughed into a lamppost, which ended up in someone’s garden.

I panicked. I ran back to the Rose and Crown and sat there with my mates like nothing had happened. My plan was to pretend that the car had been stolen. It wasn’t long before the police arrived and a copper was tapping me on the back.

‘Excuse me, Mr Merson,’ he said. ‘Do you know your car has been crashed into a lamppost which is now in some-one’s garden?’

I played dumb. ‘You’re kidding?’

‘Has it been stolen?’ he asked.

I kept cool. It wasn’t hard, I’d been taking plenty of fluids. ‘Well, it must have been,’ I said, ‘because I’ve been here all night.’

The copper seemed to believe me. He offered to take me to the car, which I knew was in a right state, but just as I was leaving the pub a little old lady shouted out to us. She’d been sat there for ages, watching me.

‘He’s just got in here!’ she shouted. ‘He tried to drive his car home!’

That was it, I was done for and the policeman breathalysed me. In the cells an officer told me I’d been three times over the limit.

‘Shit, is that bad?’ I said.

He shrugged. ‘Yeah,’ he said. ‘But it’s not the worst one we’ve had tonight. We’ve just pulled a guy for being six times over. But he was driving a JCB through St Albans town centre.’

I was banned from driving for 18 months; the club suspended me for two weeks and fined me £350. Like that JCB in St Albans town centre, I was spinning out of control.

George said the same thing to me whenever I got into trouble: ‘Remember who you are. Remember what you are. And remember who you represent.’

That never dropped with me, I never got it. I was just a normal lad. I came from a council estate. My dad was a coal man. My mum worked in a Hoover factory at Hangar Lane. We were normal people and I wanted to live my life as normally as I could. I had the best job in the world, but I still wanted to have a pint with my mates. Along the way, that attitude was my downfall.

The club never really cottoned on that the drinking was starting to become a problem for me. They would never have believed that I was on my way to being a serious alcoholic. I didn’t know either. I thought I was a big hitter in the boozing department and that it was all under control. The first I knew of my alcohol problem was when they told me in the Marchwood rehab centre.

I used to put on weight because of the beer, but the Arsenal coaches never sussed. I’d worked out that when I stood on the club weights and the doc took his measurements, I could literally hold the weight off if I lent at the right angle or nudged the scales in the right way. The lads used to give me grief all the time. They used to point at my love handles and say I was pregnant, and when George walked past me in the dressing-room I’d suck my tummy in to hide the bulge. I could never have worn the silly skin-tight shirts they wear now, my gut was that bad.

People outside the club would see me drinking, and George would get letters of complaint, but I used to brush them aside when he read them out to me.

‘Paul Merson was in so and so bar in Islington,’ he’d read, sitting behind his desk, waving the letters around. ‘He was drunk and a disgrace to Arsenal Football Club.’

I’d make out they were from Tottenham fans. Then, when I got a letter banging on about how I’d been spotted drunk in town when I’d really been away with the club on a winter break, I was made up. I knew from then on I had proof that there were liars making stuff up about me. I blamed them for every letter to the club after that, even though most of them were telling the truth.

I wasn’t the only one causing aggro, my team-mates were having a right old go, too. In 1989, the year we won the title, I bought a fancy, new, one-bedroom house in Sandridge, near St Albans. It was lovely, fitted with brand-new furniture. I loved it, I was proud of my new home.

Tony Adams was one of my first guests, but he outstayed his welcome. In April 1989 we played Man United away, drew 1–1 and Tone got two goals, one for us and a blinding own goal for them. He fancied a drink afterwards, like he always did in those days, but time was running out as the coach crawled back to London at a snail’s pace and we knew the pubs would be kicking out soon. That wasn’t going to stop him, though.

‘We’re not going to get back till nearly 11, Merse,’ he said. ‘Can I stay at yours and we’ll have a few?’

I was up for it. I never needed an excuse for a drink, but at that stage in the campaign, we’d been under a hell of a lot of pressure. We’d started the season on fire, and even though we weren’t a worldy side (nowhere near as good as the team that won the title in 1991), at one stage we were top of the First Division by 15 points. Then it all went pear. We’d drawn too many matches against the likes of QPR, Millwall and Charlton. Shaky defeats at Forest and Coventry had put massive dents in our championship hopes. After leading the title race for the first half of the season our form had dropped big-time and Liverpool were hot on our heels. That night I wanted to let off steam.

I knew I could get a lock-in at the Rose and Crown. I called up my missus and asked her to make up our fancy brand-new sofa bed for Tone when we got back. Once the team coach pulled up at the training ground, we got into Tone’s car and drove to the pub.

We finished our last pint at four in the morning. Tone gave me a lift back to the house and nearly killed us twice, before parking in the street at some stupid angle. I crept inside, not wanting to wake Lorraine, put Tone to bed and crashed out. When I woke up later, Lorraine was standing over me with a copy of the Daily Mirror in her hand.

‘Look at what they’ve done to him!’ she said, showing me the back page.

Some smart-arse editor had drawn comedy donkey ears on a photo of Tone. Underneath was the headline, ‘Eeyore Adams’. And all because he’d scored an own goal. He’d got one for us too, but that didn’t seem to matter.

‘What a nightmare,’ I said.

‘Are you going to tell him?’

‘Bollocks am I, let him find out when he’s filling up at the petrol station.’

I could hear Tone getting his stuff together downstairs. Then he shouted out to us, ‘See you later, Merse! Thanks for letting me stay, Lorraine!’

When I heard the front door go, I knew we were off the hook. Lorraine got up to sort the sofa bed out so we could watch the telly, and I got up to make a cup of tea. Then Lorraine started shouting. ‘He’s pissed the bed!’

I looked over to see her pointing at a wet patch on our brand-new furniture. I was furious. I grabbed the paper and chased down the street after Tone as he pulled away in his car.

‘You donkey, Adams!’ I shouted. ‘You’re a fucking donkey!’