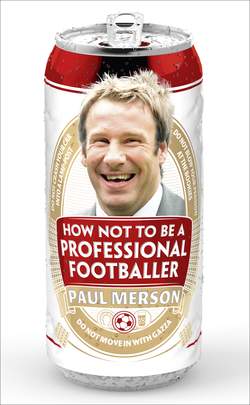

Читать книгу How Not to Be a Professional Footballer - Paul Merson - Страница 8

ОглавлениеLesson 3

Do Not Cross Gorgeous George

‘Because hell hath no fury like a gaffer scorned.’

After Tone’s bed-wetting incident and the 1–1 draw with Man United, Arsenal started to fly again. We beat Ever-ton, Newcastle and Boro and spanked Norwich 5–0. The only moody result was a 2–1 away defeat at Derby County which allowed Liverpool to leapfrog us in the League with one game to go. Along the way, I got us some important goals. There was an equaliser in a 2–2 draw against Wimbledon in the last home game of the season which kept us in the chase for the League, but my favourite was a strike against Everton in the 3–1 win at Goodison Park. I got on to the end of a long ball over the top and banged it home. When it flew past their keeper, Neville Southall, I ran up to the Arsenal fans, hanging on to the cage that separated the terraces from the pitch.

I loved celebrating with the Arsenal crowd. It was a completely different atmosphere at football matches back then. There was a real edge to the games. Remember, this was a time before the Hillsborough disaster and the Taylor Report and there were hardly any seats in football grounds. Well, not when you compare them with today’s fancy stadiums. The fans swayed about and the grounds had an unbelievable atmosphere. I loved it when there were terraces. Football hooliganism was a real problem back then, though. It could get a bit naughty sometimes.

I’d always learn through mates and fans when there was going to be trouble in the ground. If Arsenal were playing Chelsea at Highbury, I’d always hear whispers that their lot would be planning on taking the North Bank in a mass ruck. The players would talk about it in the dressing-room before games, and whenever there was a throw-in or a break in the play, I’d look up at the stands, just to see if it was kicking off.

You could have a bit of fun with the supporters in those days, and we often laughed and joked with them during the games. If ever we were playing away and the home lot were hurling insults at us, we’d give it back when the ref wasn’t looking. It happened off the pitch as well, but sometimes we went too far.

I remember when Arsenal played Chelsea at Stamford Bridge in 1993. After the game a group of their fans started chucking abuse at our team bus, they were even banging on the windows. I was sat at the back, waiting for Steve Bould’s eating competition to kick off, when all of a sudden our striker, Ian Wright, started to make wanker signs over the top of the seats. All the fans could see was his hand through the back window, waving away. They couldn’t believe it.

I nearly pissed myself laughing as the coach pulled off, but I wasn’t so happy when we suddenly stopped a hundred yards down the road. The traffic lights had turned red and Chelsea’s mob were right on top of the bus. They were throwing stuff at the windows, lobbing bottles and stones towards Wrighty’s seat. All I could think was, ‘Oh God, please don’t let them get on, they’ll kill us.’ Luckily the lights changed quickly enough for us to pull away unhurt. I don’t think anyone had a pop at the fans for quite a while after that.

All of a sudden, I was in the big time and so were Arsenal. By the time the 1988–89 season was in full swing, my name was everywhere and I had a big reputation. George had made me a regular in his team and I’d started 35 games, scoring 14 times as centre-forward. I did so well I was awarded the PFA Young Player of the Year. I even had nicknames – the Highbury crowd called me ‘Merse’ or ‘The Magic Man’. There was probably some less flattering stuff as well, but I didn’t pay any attention to that.

With our defeat at Derby and draw against Wimbledon, and Liverpool’s 5–1 win over West Ham, the title boiled down to the last game of the season, an away game at Anfield on Friday 26 May. Liverpool were top of the table by three points, we were second. Fair play to them, they’d been brilliant all year and hadn’t lost a game since 1 January. We still had a chance, though. We knew that if we did them by two goals at Anfield, we’d pinch it on goal difference.

Anfield was the ultimate place to play as a footballer back then. Before a Saturday game at Liverpool, probably around 1.30, the away team would go on to the pitch to have a walk around. George liked us to check out the surface and soak up the atmosphere on away days. Anfield was always buzzing because the Kop was packed from lunchtime. They’d sing ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’, wave their scarves, and surge backwards and forwards, side to side, like they were all on a nightmare ferry crossing to France. It always made me double nervous.

‘Oh shit,’ I’d think. ‘Here we go.’

Weirdly, I wasn’t nervous when we played them at their place on the last day of the 1988–89 season, mainly because nobody had given us a cat-in-hell’s chance of winning the League. Nobody won by two goals at Anfield in those days. Before the game, my attitude was, ‘No way, mate. It ain’t happening.’

The game had become a title decider because of the Hillsborough disaster. It had originally been scheduled for April, but after the FA Cup semi-final between Liverpool and Forest at Sheffield Wednesday’s ground, where 96 Liverpool fans were crushed to death in the stands before kick-off, it was postponed until the end of May, after the final. Liverpool got through against Forest and won the FA Cup, beating Everton of all teams 3–2, not that any Everton fan would begrudge them after all that. Now it was up to us to stop them from doing the double.

I could understand the faffing about with the fixtures, because Hillsborough was one of the worst things I’d ever seen in football. In 1985, I’d watched the Heysel Stadium disaster on the telly. It made me feel sick. I’d turned on the telly hoping to see the European Cup Final between Liverpool and Juventus, but instead I watched as bodies were being carried out. A riot had kicked off, and as fans tried to escape the trouble a wall collapsed on them. Hills-borough was just as bad. I was supposed to pick up my PFA Young Player of the Year Award at a fancy ceremony on the day that it happened, but after seeing the tragedy on the news, I really wasn’t interested. Everything seemed insignificant after all those deaths.

The fixture change pushed us together on the last day of the season in a grand finale. Because the odds were stacked against us and everyone was writing Arsenal off, it had become a free game for the lads, a bonus ball on the calendar. In our heads, we knew George had turned the team around after Don had resigned. Considering Arsenal hadn’t won the League for ages, coming second in the old First Division in 1989 would have been considered a massive achievement by everyone, even though we’d been top for ages before falling away. We were still a young side, discovering our potential, and there was no shame in being runners-up behind an awesome Liverpool team that included legends like Ian Rush, John Aldridge, John Barnes, Peter Beardsley and Steve McMahon. It would have been phenomenal really.

George still pumped us full of confidence. During the week before the game he banged on about how good we were and how we could beat Liverpool. He planned everything as meticulously as he planned his appearance, which was always immaculate. We went up to Merseyside on the morning of the game that Friday, because George wanted to cut out the nerves that would have built up overnight if the team had stayed together. We got into our hotel in Liverpool’s town centre at midday, ate lunch together and then went to our rooms for a three-hour kip.

I never roomed with anyone in those days, because nobody would share with me. The main reason was that I could never get to sleep. I was too excitable and that always drove the other lads mad. Nobody wanted to deal with my messing around before a big game, but in the end I got to enjoy my own privacy. The great thing about having a room to myself was that I could wax the dolphin whenever I wanted.

At five-thirty we all went downstairs for the tactical meeting and some tea and toast. George lifted up a white board and named the team: John Lukic in goal; a back five of Lee Dixon, Nigel Winterburn, Tone and Bouldy, with David O’Leary acting as a sweeper. All very continental. I was in midfield with Rocky, Mickey and Kevin Richardson. Alan Smith was playing up front on his own. George told us who was picking up who at set-pieces, and then he told us how to win the game.

‘Listen, don’t go out there and try to score two goals in the first 20 minutes,’ he said. ‘Keep it tight in the first half, because if they score first, we’ll have to get three or four goals at Anfield and that’s next to impossible. Get in at half-time with the game nil-nil.

‘In the second half, you’ll go out and score. Then, with 15 minutes to go, I’ll change the team around, they’ll shit themselves, you’ll have a right old go, score again and win the game 2–0. OK?’

Everyone looked at each other with their jaws open. Remember, Liverpool hadn’t lost since New Year’s Day. I turned round to Bouldy and said, ‘Is he on what I’m on here?’

None of us believed it was going to happen, not in a million years, but we really should have had more faith in George. He was one of those managers who had so much football knowledge it was scary. People said he was lucky during his career, but George made his own luck. Things happened for him because he worked for it. He was always saying stuff like, ‘Fail to prepare, prepare to fail.’ He’d read big books like The Art of War. I couldn’t understand any of it.

When we kicked off, I thought George had lost the plot. In the first half, Liverpool passed us to death. I touched the ball twice and we never looked like scoring. They never looked like scoring either, but they didn’t have to. A 0–0 draw would have won them the title, so they were probably made up at half-time. The really weird thing was, George was made up as well.

‘Great stuff, lads,’ he said. ‘Brilliant, perfect. Absolutely outstanding. The plan’s going perfectly.’

I couldn’t make it out. George was never happy at half-time. We could have been beating Barcelona 100–0 and he’d still be angry about something. I turned round to Mickey.

‘You touched it yet?’ I said.

He shrugged his shoulders. Everyone was looking at the gaffer in disbelief.

Then we went out and scored, just like George had reckoned we would. It came from a free-kick. The ball was whipped in and Alan Smith claimed he got his head to it. I wasn’t sure whether it had come off his nose, but I couldn’t have cared less – we were 1–0 up. It could have been even better, because moments later Mickey was bearing down on Bruce Grobbelaar’s goal, one-on-one. In those days, you had to have some neck to win 2–0 at Anfield. Often the Kop would virtually blow the ball out of the net. It must have freaked Mickey out because he fluffed it. All I could think was, ‘Shit, we’ve blown the League.’

Then it was game over, well, for me anyway. George took me off and brought on winger Martin Hayes, pushing him up front. Then he pulled off Bouldy and switched to 4-4-2 by replacing him with Grovesy, an extra midfielder. This was where Liverpool were supposed to shit themselves, but I was the one who was terrified. I had to watch the closing minutes like every other fan.

We were playing injury time. Their England midfielder, Steve McMahon was running around, wagging his finger and telling the Liverpool lot we only had a minute left to play. Winger John Barnes won the ball down by the corner flag in our half. He was one of the best English players I’d ever seen, but God knows what he was doing that night. All he had to do was hang on to possession and run down the clock, but for some reason he tried to cut inside his man. Nigel Winterburn nicked the ball off him and rolled it back to John Lukic who gave it a big lump down field. There was a flick on, and suddenly Mickey was one-on-one with Grobbelaar again.

This time, he dinked the ball over him. It was one of the best goals I’d ever seen, one of those chips the South Americans call ‘The Falling Leaf’ – where a player pops the ball over an advancing keeper. It was never going to be easy for Mickey to chip someone like Grobbelaar, especially after missing a sitter earlier in the game, and he had a thousand years to think about what he was going to do as he pelted towards goal – talk about pressure. Mickey kept his head and his goal snatched a famous 2–0 victory and the League title.

When I think about it, that’s probably one of the most famous games ever. Even if you supported someone like Halifax, Rochdale or Aldershot at that time, you’d still remember that match, especially the moment when commentator Brian Moore screamed, ‘It’s up for grabs now!’ on the telly, or the image of Steve McMahon wagging his finger, giving it the big one. Afterwards he was sat on his arse. He looked gutted.

It was extra special for Arsenal. We hadn’t won the League for 18 years and the Kop later applauded us off the pitch. It was a nice touch. Liverpool were the best team in the land at that time. They probably figured another title would turn up at their place, sooner rather than later.

The celebrations started straight after the game. I cracked open a bottle of beer with Bouldy in the dressing-room, still in my muddy Arsenal kit. After that, we got paro on the coach home and ended up in a Cockfosters nightclub until silly o’clock. There was an open-topped bus parade on the Sunday, but everything is a blur to me. The next thing I remember it was breakfast time on Tuesday morning. I was trying to get my keys into my front door, waking up the whole street. I still haven’t got a clue what happened in those 72 hours or so in between. These days, whenever a 22-year-old comes up to me and asks for an autograph, the same thought flashes through my mind: ‘Oh, for fuck’s sake, please don’t call me Dad.’

The lads at the club called me ‘Son of George’ because they reckoned I got away with murder. They were probably right. I certainly didn’t get bollocked as much by the manager as the others, even though I was probably the most badly behaved player in the squad. For some reason, George really took a shine to me.

I remember one time when we went to a summer tournament in Miami in 1990. It was a bloody nightmare. The weather was so hot we had to train at 8.30 in the morning. One day, I stood on the sidelines, yawning, scratching my cods, when George jogged over and looked at my hand. It was halfway down my shorts.

‘You all right, Merse?’

‘Yeah, I’m fine,’ I said.

George put his arm around my shoulder. ‘No, no, you sit down, son,’ he said, thinking I’d pulled a groin muscle.

He was worried I might have overdone it in training, but the only thing I’d been overdoing was a little dolphin waxing in my hotel room.

‘Sit out this session, and don’t worry about it,’ he said.

I could see what the rest of the lads were thinking as I lazed around on the sidelines, and it wasn’t complimentary. Moments later, Grovesy and Bouldy started rubbing their own wedding tackles, groaning, hoping they’d get some of the same treatment, but George was having none of it.

That was how it was with me and George, he was good as gold all the time. He always told me up-front when I wasn’t playing, whether that was because he was dropping me or resting me. He knew I couldn’t physically cope with playing five games on the bounce because I’d be knackered. He liked to rest me every now and then, but he always gave me a heads-up. With the other lads, George wouldn’t announce the news until he’d named the team in the Friday tactical meeting. It would come as a shock to them and that was always a nightmare, because the whole squad would make noises and pull faces. George would always pull me to one side on Thursday, so I could tell the lads myself, as if I’d made the decision. He’d never let me roast.

As I went more and more off the rails throughout my Arsenal career, he must have given me a million chances. God knows why. After my run-ins with the law and the drink-driving charge, word got around the club about my problems, and George started to get fed up with the drinking stories as they started to happen more regularly. I was forever in his office for a lecture. If I’d been caught drinking again or misbehaving, he would remind me of my responsibilities, but he’d never threaten to kick me out of the club or sell me, even though I was high maintenance off the pitch.

I was saved by the fact that I never had any problems training. No matter how paro I’d got the night before, I rarely had a hangover the next morning, I was lucky. I could always tell when some players had been drinking by the way they acted in practice games – they couldn’t hack it. Me, I could always get up and play. I didn’t enjoy it, but I could get through the day, and George knew that come Saturday I’d be as good as gold for him.

Well, most of the time. In some games I played while still pissed from the previous night. In 1991 we faced Luton Town away on Boxing Day. On Christmas Day, the players had their lunches at home with the families, then we met up at Highbury for training. Afterwards, we piled on to the coach to the team hotel and I knocked back pints and pints and pints in the bar. I couldn’t help it, it was Christmas and I was in the mood. The next day, I was still hammered. During the game, a long ball came over and I chased after it. As I got within a few yards I tripped over my own feet, even though there wasn’t a soul near me. I could hear everyone in the crowd laughing and jeering. I couldn’t look towards the bench.

Even though I was Son of George, the manager would always bollock me really hard whenever he caught me drinking. I was even the first player ever to be banned from Arsenal when I caused a lorryload of trouble at an official dinner and dance event for the club at London’s Grosvenor House Hotel. The ban was only for two weeks in 1989, but it caused one hell of a stink all the same.

I was hitting the booze pretty hard that night, and this was a fancy do with dinner jackets, a big meal, and loads of beers flying around. I got smashed big-time, drinking at the bar and having a right old laugh. I was so loud that my shouting drowned out the hired comedian, Norman Collier, who was entertaining the club’s guests – including wives, directors and VIP big shots. People turned round and stared at me as I knocked back drink after drink. George and the Arsenal board were taking note.

Later, a big punch-up kicked off in the car park outside the hotel and somehow I was in the thick of it. To this day I still don’t know what happened, because I was so paro. The papers got to hear about the scuffle, and so did the fans. The next day, George told me to sort myself out and not to come back for a couple of weeks. I wasn’t even allowed to train and being shut out scared me.

I spent a fortnight lying low, trying to convince myself that I’d get back on the straight and narrow. For a while it worked. When I came back I was as good as gold, then I started downing the beers again. The Tuesday Club was into the swing of things and I was back on the slippery slope.

I got worse, and whenever I messed up and George found out, he would do me. On New Year’s Day in 1990, we were playing Crystal Palace at Selhurst Park. I was told I wasn’t in the team.

‘Nice one,’ I thought. ‘It’s New Year’s Eve and I’m in a fancy hotel with the rest of the team, let’s get paro.’

I figured being dropped was a green light for me to go out for a drink and a party. This time, I got so smashed I couldn’t even get up in the morning. George found out and named me as sub for the match just to teach me a lesson. When I fell asleep on the bench during the game, he brought me on for the last 10 minutes to give me another slap. I couldn’t do a thing – I was like a fish up a tree. I couldn’t control the ball and I felt sick every time I sprinted down the wing. We won 4–1, but after that night George vowed never to name a team on New Year’s Eve again. On a normal Saturday he would have got away with it, because I’d have behaved, but I was becoming an alcoholic and it was New Year’s Eve. It had been a recipe for disaster.