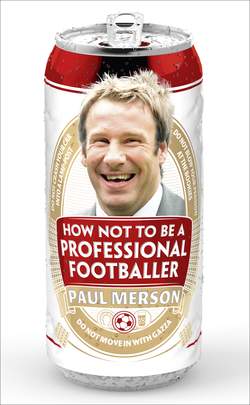

Читать книгу How Not to Be a Professional Footballer - Paul Merson - Страница 9

ОглавлениеLesson 4

Do Not Shit on David Seaman’s Balcony

‘More boozy disasters for our football dynamo; Perry Groves nearly drowns.’

Oh my God, Gus Caesar was as hard as nails. When he played in the Arsenal defence he always had a ricket in his locker and the fans sometimes got on his back a little bit because he made the odd cock-up, but what he lacked in technique he definitely made up for in physique. He was the muscliest footballer I’d ever seen. I reckon he could have killed someone with a Bruce Lee-style one-inch punch if he wanted. A lot of the time, I got the impression he was just waiting for an excuse to try it out on me. I had a habit of rubbing him up the wrong way.

It all kicked off with me and Gus in 1989, when Arsenal took the players away to Bermuda for a team holiday. The whole squad went to a nightclub and got on the beers one night, messing around, having a laugh. All of a sudden Gus started shouting at me. A drunken argument over nothing, a spilt pint maybe, had got out of hand. A scuffle broke out – handbags stuff, really – and Gus poked me in the eye just as the pair of us were being separated.

It bloody hurt and I was proper angry, but because I wasn’t much of a fighter I knew that poking Gus back would have been stupid. He would have torn me limb from limb. I reckoned on a better way to get my own back, so I let the commotion calm down, staggering away, bellyaching, checking to see if I was permanently blind. Then Bouldy and me went back to the hotel, leaving everyone behind. We walked up to reception, casual as you like, and blagged the key to Gus’s door. It was party time, I was going to cause some serious damage to his room.

In hindsight it was a suicidal move, because Gus was sharing with midfielder Paul Davis, who was hardly a softie. He’d infamously smacked Southampton’s midfield hardman, Glenn Cockerill, in the middle of a game in 1988. The blow knocked him out cold and the punch was all over the papers the next day because it had been caught on the telly. Paul was banned for nine games after the FA had viewed the video evidence, which was unheard-of in those days, and Glenn slurped hospital food through a wired jaw for the best part of a fortnight. We all knew not to cross Paul, but that was in the sober light of day. I was well gone and angry that night, so I didn’t care.

Once I’d got into Gus and Paul’s room, I went mental and trashed it. I stamped on a very expensive-looking watch and smashed the board games that were lying around on the floor. Footballers didn’t have PlayStations in those days, Monopoly was the closest thing we had to entertainment without draining the minibar, and we’d done that already. Then I threw a bucket of water up on to the ceiling, leaving it to drip, drip, drip down throughout the night. It was a five-star hotel, but I couldn’t give a toss. I threw a bed out of the balcony window, then me and Bouldy laughed all the way back to our room.

I woke up not long afterwards, still pissed. Everything was swimming back to me – the fight, Gus jabbing me in the eye and the red mist coming down. An imaginary crime scene photo of the trashed hotel room slapped me around the face like a wet cod. In my head it looked like it was CSI: Merse. I sat up in bed with that horrible morning-after-the-night-before feeling and started moaning, my head in my hands.

‘Oh no, what the fuck have I done?’ I whispered.

In a panic I got dressed and padded across the corridor, hoping I could tidy up the mess before the lads got back, but it was too late. Paul Davis had pinned a note to the door.

‘Gus, the little shits have busted the room up. Just leave it and go to sleep somewhere else. Paul.’

I crawled back to bed, knowing I was done for. Hours later, the phone in our room started ringing. It was George. He was not happy.

‘Room 312. Now!’ he shouted.

Bouldy got up. I tried to pull myself together, splashing my face with water and hauling on my shorts and flip flops. It was a lovely day outside, the sun was scorching hot and there wasn’t a cloud in the sky, but it might as well have been a pissing wet morning in St Albans for all I cared. I felt sick to the pit of my stomach as we made the Walk of Death to Room 312, which I knew was Paul and Gus’s room.

When we walked in, I thought I’d arrived in downtown Baghdad. Water dripped from the ceiling. The board games were in pieces and all the plastic parts were scattered over the floor. It turned out they had belonged to the kids of club vice-chairman David Dein. He‘d lent them to the squad for the week, believing we’d appreciate the gesture, seeing as we were grown adults. The balcony window was wide open and I could see a bed upended by the pool outside. Then I realised the lads were sitting there in the room, all of them staring at me. Tone, Lee Dixon, Nigel Winterburn, Alan Smith and George. In the corner, Gus was twitching on a chair with his shirt off. His muscles were rippling and his jaw was clenched shut. His breathing sounded funny. Behind him, Paul Davis was massaging his shoulders, glaring at me like I was a murderer. Gus looked like a prize fighter waiting to pummel somebody.

George stood up and started the dressing-down.

‘What’s all this, Paul?’

‘Yeah, I know boss,’ I said. ‘Me and Gus had a bit of an argument and I came back here and trashed his room.’

He nodded, weighing up the situation. ‘Well, why don’t you go outside now and sort it out between yourselves?’ he said.

What? I started shaking. Gus looked like a caged Rottweiler gagging for his dinner. I’d sobered up sharpish, because I knew I didn’t want to fight Gus – he would have killed me. Gus knew it too and was cracking his knuckles, working the muscles in his upper body. Then Paul Davis piped up.

‘Yeah, why don’t you go outside and sort it out, Merse? Fight him.’

Fuck that. I backed down, apologised, grovelled, and took my punishment. Nobody spoke to me for two months afterwards, and I was chucked out of the players’ pool. That was bad news. The players’ pool was a cut of the TV money which was shared out among the team from Arsenal’s FA Cup and League Cup runs. That added up to a lot of cash in those days. I could earn more money from the players’ pool than from my wages and appearances money put together. I was gutted.

It was George’s way to keep us in check through our wallets. When I won the League in 1989, my wages were £300 a week, with a £350 bonus for a win and £200 for an appearance. In a good month I could clock up three or four grand. There were never any goal bonuses in those days, because George reckoned they would have made us greedy, but if you look at the old videos now, you can see we all jumped on one another whenever we scored. That was because we were getting more dough for a win than our weekly wage. Everyone was playing for one another, it was phenomenal, but if you looked at the subs’ bench, it was always moody. Life on the sidelines was financially tough for a player, because we were only getting the basic £300.

Still, George made a point of keeping the lads close financially. Some of the team now feel a bit fed up with him because they didn’t earn the money they might have done at another big club, and it’s true that we were very poorly paid compared to the other teams. But the thing is, all of those players went on to make a lorryload of appearances throughout their careers thanks to him. They earned quite a bit in the long run, so they shouldn’t have a bad word to say about the bloke.

It’s a million miles away from the game today, but I’ve got no qualms about top, top players making great money. They’re entertainers. Arnold Schwarzenegger makes loads of films and he can’t act, but no one says anything about him making £7 million a movie, do they? If a top player gets £100,000 a week in football, the fans say he’s earning too much, but players like that are the difference between people going to work on a Monday happy or moody.

Your Steven Gerrards, your Wayne Rooneys – these are the players that should get the serious money. My problem is with the average players getting lorryloads of cash for sitting on the bench. That’s where it’s wrong. From an early age, players should be paid on appearances, just like George had set us up at Arsenal. They should get 33.3 percent in wages, 33.3 percent in appearance money and 33.3 percent in win bonuses.

It gives the players incentives; it stops people slacking off. I’ve seen it with certain strikers enough times. They are on fire, then they sign a new contract and never kick the ball again. They don’t look interested. They move to a new club and do the same. Those things sicken me, but not all footballers are like that. When you look at players like Ryan Giggs and Paul Scholes, they seem like proper professionals. They score at least eight out of 10 ratings for their performance levels every year, and they’ve won everything in the game 10 times over. They’re still churning it out. I never hear them complaining about money. Well, they’re at United, so they probably don’t have to.

My mucking around in Bermuda was par for the course really. Every year George liked to take the squad to Marbella in Spain for a short holiday. We’d go three times a season, the idea being that a few days in the sun would freshen the lads up before a big run of games. We’d meet at the airport on a Sunday morning, and by Sunday evening I’d be paro, usually with Grovesy. I loved it.

One year we went away when it was Grovesy’s birthday. Neither of us was playing because of injuries, so we went out on the piss, hitting the bars on Marbella’s water-front. By the time we’d staggered into Sinatra’s, a pub by the port, all the lads were drinking and getting stuck into dinner. I was hammered. When the condiments came over, I squirted Grovesy with a sachet of tomato ketchup. The sauce splattered his face and fancy white shirt. Grovesy squirted me back with mustard and within seconds we were both smothered in red and yellow mess.

Then the lads joined in. Because it was Grovesy’s birthday, we jumped on him and grabbed his arms and legs. Some bright spark suggested dunking him in the sea, which was just over the road. Tourists stared and pointed. God knows what they must have thought as they watched a group of blokes they’d probably recognised from Match of the Day staggering across the street, dragging a screaming team-mate towards the tide.

We lobbed him over a small wall and I waited for the splash and Grovesy’s screams.

There was no noise. We couldn’t see over the rocks. I started to brick myself. How far down was the water? Nobody had checked before throwing him in.

Finally … splash!

Then there was screaming – thank God. The lads started laughing, nervously. We peered over the edge and saw a ginger head and thrashing arms. He was about 20 miles below us, thrashing about in the waves. Grovesy was panicking, trying to swim towards the rocks. He was chucking all sorts of abuse at us, so nobody tried to help him out, and nobody offered any sympathy as he squelched all the way home.

Grovesy was used to stick. My party piece was to shit in his pillow case just to really wind him up. I used to love seeing the look on his face as he realised I’d left him a little bedtime pressie. When he caught me the first time, squatting above his bed, letting one go, he couldn’t believe his eyes.

‘Merse, what the fuck are you doing?’ he screamed.

I didn’t stop to explain.

When Grovesy left Arsenal for Southampton I was sad to see him go, but when I started sharing a room with midfielder Ray Parlour, I realised I’d found someone who was just as lively. That holiday, George had put us into a room next door to our keeper, David ‘Spunky’ Seaman, who had signed in 1990, and Lee Dixon. We called them the Straight Batters, because they never got involved with the drinking and messing around like some of us did. They were always the first to bed whenever we went out on the town. I was the complete opposite. I rarely slept on club holidays, and I’d always pay the bar staff a fair few quid to leave out a bin of beers and ice for when we got back from the pub. That way we could drink all night.

One morning Dixon and Spunky went off for a walk while Ray and me snored away our hangovers. When I woke up I needed the khazi, so, still half cut, I thought it would be funny to bunk over the adjoining balcony and put a big shit in front of the Straight Batters’ sea view. I didn’t think anything of it until a few hours later when I was sitting by the pool with Ray, soaking up the sun. Suddenly I could hear Spunky going ballistic. His deep, northern voice was booming around the hotel and scaring the seagulls away.

‘Ooh the fook’s done that?!’ he yelled.

Me and Ray were falling about by the pool. Like he needed to ask.

Even though Arsenal didn’t retain the title in 1990, we were a team on the up. Liverpool ran away with it that year and I soon learnt that everyone wanted to beat the champions, which made the games so much harder than before. We got spanked 4–1 by Man U away on the first day of the season. It was a real eye-opening experience. I remember that game well, not just because of the battering we took, but because United’s supposed next chairman, Michael Knighton, came out on to the pitch making a big song and dance, showing off about how he was going to buy the club. He had his United shirt on and he came out doing all these keepy-ups, while we stared at him.

‘Who the fuck is this bloke?’ I thought.

He smashed the ball home and waved to the crowd as he ran off. It turned out that he didn’t have quite the financial backing the fans thought he had.

The United game set the tone for the season, and we lost too many important games during the campaign – Liverpool, Spurs, Southampton, Wimbledon, Sheffield Wednesday, QPR and Chelsea all managed to beat us along the way. It was hardly the form of champions. We ended up in fourth spot, which was disappointing after the year before.

The fact that we weren’t going to win the League that year caused complacency to creep in among some of the lads, and George hated that. On the last day of the season we were due to play Norwich City. Liverpool were streets ahead. We couldn’t qualify for Europe because of the ban on English teams after the Heysel disaster, and we couldn’t go down, so it was a nothing game really.

I was injured, and the day before the match was a scorcher. I got together with Bouldy, Grovesy and Nigel, and after training we strolled down to a nearby tennis club for a pint. We had three beers each and some of the other lads came in at different times and had a beer or two and left, but the bar staff didn’t collect the bottles as we sat there. After an hour the table was swamped with empties. Then George walked in with his coaching staff, jumper draped over his shoulders like Prince Charles on a summer stroll.

The thing with Gorgeous George was that he was proud of his looks and he liked to live in luxury. One time, when we flew economy to Australia for a six-a-side tournament with Man City and Forest, George sat in first class while the great Brian Clough sat in the same seats as the players. The message was clear: George wanted to keep his distance.

Now he eyed the bottles. ‘Having a good time, lads?’ he said, happy as you like. ‘Yeah, cheers, boss,’ we said, thinking we’d got away with it.

As he strolled off, I honestly thought that was the end of the matter. In fact, he didn’t mention it again all weekend. As far as we were concerned it was forgotten. We drew 2–2 with Norwich, and the following day we flew to Singapore for seven days to play Liverpool in an exhibition match before showing up in a few friendlies with local sides. It was all Mickey Mouse stuff, really. The plan was to stay there for a week because the club were treating the players to another seven days in Bali for a holiday and we were flying out of Singapore.

I couldn’t wait, I was like a kid on Christmas Eve. The morning of our Bali flight, I sat in the hotel foyer at 10 in the morning with my bags packed. Bouldy, Grovesy and Nigel were also with me when George walked up. In those days, the clubs held on to the player’s passports, probably to stop us from doing a runner to Juventus or Lazio for bigger money, but George had ours in his hands.

‘Right, lads,’ he said, handing them out one by one. ‘Your flight home to London leaves in three hours. I’ll see you when we get back from our holiday.’

There was a stunned silence as George turned his back on us to take the rest of the lads to Bali for a jolly. We were later told it was because we’d been caught drinking before the Norwich game. Our summer hols had been cancelled, but I don’t think my case had been helped when I was caught throwing an ashtray at a punter in a Singapore nightclub a few nights earlier. We were later fined two-weeks’ wages. On the way home nobody spoke, we didn’t even drink on the plane. I only used to have a beer when I knew I wasn’t supposed to have one. That day it hardly seemed worth it.

I should have guessed that George would let loose on the Singapore trip, because in between the beers at Norwich and our early flight home, Tone had been done for drink-driving. As a defender, he was top, top drawer and would run through a brick wall for Arsenal. The problem was, he’d driven through one as well, pissed out of his face the night before we were due to fly east. The police turned up and gave him the breathalyser test, and Tone was nicked. He was the Arsenal captain and well over the limit. Someone was always going to cop it from the gaffer after that.

The funny thing was, when Tone turned up late at the airport looking like he’d been dragged through a hedge, nobody said anything at first. We’d been waiting for him at the airport for so long that it looked like he wasn’t going to show. We were just relieved to be getting on the plane. It was only when he got into his seat and said, ‘Bloody hell, I’ve been done for drink-driving,’ that we got an idea of what had happened, but even then nobody batted an eyelid because we all knew he was a Billy Bullshitter.

Tone was forever making stuff up, and he’d built up quite a reputation around the club. I could be sitting there at the training ground, reading the Sun, and just as I was turning over to Page 3 for an eyeful, he’d lean across.

‘I’ve fucked her,’ he’d say, pointing to the girl in the picture.

‘Piss off, Tone,’ I used to say. ‘You look like Jimmy Nail.’

Then he ended up going out with Caprice for a while. She was a model, and a right fit one at that, so maybe he was getting lucky with Britain’s favourite lovelies after all. That day, though, no one was having it. Even as he was brushing glass from his hair on the plane, the lads thought he was pulling a fast one.

When we got to Singapore we knew it wasn’t a wind-up because it was all over the news. By the time the English papers had turned up, the whole club knew about it. Everyone at home was making out he was a disgrace to football, and the fans were worried that he might buckle under the pressure, but Tone had a seriously strong character. If anyone was going to get through it unscathed it was him.

You have to remember that he’d already shouldered a lot of pressure. When he made his Arsenal debut against Sunderland in 1983 he’d been ripped to shreds by a striker called Colin West. Tone was only 17 and it was probably one of the worst debuts by a defender in the history of the game. The golden rule of football is that everyone has a good debut – especially if you play up front, because there’s no expectations. You always get a goal, and I scored on my full debuts for Arsenal, Villa and Walsall. In his first ever professional game Tone had a shocker, but he got through it. Later, in the 1988 European Championships, he played for England in the group stages against Holland and was torn apart by Marco van Basten. It was horrible to watch, but he bounced back from that too. Even before the Daily Mirror’s ‘Eeyore Adams’ headline, the fans used to make donkey noises at him wherever he played, and while it gave him the hump sometimes, it never affected his game.

I knew Tone would pull through, even when he was later banged up on account of the drink-driving incident. But to be honest, I was just relieved it wasn’t me in the shit for once. I’d had more than my fair share of naughty newspaper headlines. This time, I was out of the limelight. The calm before the storm, I think they call it.