Читать книгу Arctic Solitaire - Paul Souders - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

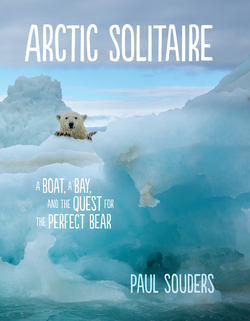

CHAPTER 1 THE ICE BEAR

ОглавлениеAll the easy pictures have been taken. But I’m here to tell you there are still some stupid and crazy ones left out there.

I was heading north with at least one of them in mind; I was looking for the polar bear of my dreams. Not a zoo bear, not some hanging-around-the-towndump bear, and certainly not a Tundra Buggy tourist bear. I was searching for a polar bear living unafraid and standing unchallenged at the very top of the food chain. I planned to photograph that bear living, hunting, and swimming among the melting Arctic sea ice.

My plan to accomplish this was, to put it charitably, a little vague. I imagined that if I gathered up enough survival and camera gear, found a way to haul it halfway across the continent to the end of the road in Canada’s north woods, and loaded it all onto a train bound for the shores of Hudson Bay . . . then somehow or other I would be able to go out and find that polar bear. I’m not always big on details.

Working as a professional wildlife photographer, I have always liked doing things the hard way, slapping together my own solo expeditions and then figuring it all out along the way. Is it because I’m difficult and stubborn and cheap? Well, yes. But I’ve also found that the lessons learned through painful experience are the ones that tend to stick. Spend twenty-seven hours digging a Land Cruiser out of swamp muck with nothing but your bare hands and a small cooking pot and I wager you, too, will remember a shovel next time.

For years, I had been making noise about going to Canada’s Hudson Bay to photograph the polar bears there. Churchill, Manitoba, is a tumbledown slice of small-town Canada inexplicably plopped down along the Bay’s shore where the vast northern forests give way to Arctic tundra. It lies smack in the middle of approximately nowhere, and no road connects it to the outside world. There’s just a long, narrow-gauge railroad leading to the smash-mouth hockey capital of Winnipeg, some six hundred miles south. If you continue a mere 220 miles farther, you can warm your frostbitten toes on the tropical shores of Fargo, North Dakota.

It takes less than two hours to reach Churchill by jet from Winnipeg. It’s that or devote two long days going by slow train, if it’s running. Churchill has grown world famous for its polar bears. Each autumn, hundreds of them, grown lean and hungry during the long summer months, gather along the Bay’s western coast and wait for the freezing ice to thicken sufficiently to allow their return to the business of tracking, hunting, and eating seals. Visitors can step off the plane and, with the application of several thousand dollars, hop onto the nearest oversized, overstuffed, and overpriced Tundra Buggy, where they’ll join a gaggle of other photographers and tourists, and trundle off to see dozens of polar bears in an afternoon.

But where’s the fun in that?

Try to imagine crossing the Serengeti Plains of East Africa one hundred or even fifty years ago. To have been among the first to visit and photograph penguin-filled islands off Antarctica. To have stood alone among grizzly bears feasting upon Alaska’s spawning salmon runs. As I look around the world, it seems we’re left with nothing but ghosts, faded remnants of the wild lands and creatures that once defined our planet. I have spent the last two decades chasing shadows, caught up in a frantic scramble to create a record of those last remnants of wildness before they, too, vanish.

Sure, you can still go to some of these places, but you’d best be ready for plenty of human companionship and adult supervision. Remote wilderness destinations that once required committed professional expeditions to see and film now beckon invitingly from the pages of glossy vacation catalogs, promising gourmet cooking, free Wi-Fi, and a hot stone massage at dusty day’s end. All to join two dozen other enthusiasts who will, often as not, stand shoulder to shoulder with tripod legs entwined and shoot the same perfectly lovely, utterly identical photographs.

Making great pictures once required years of training and practice and, I liked to tell myself, no small measure of genius. New digital technology and modern autofocus lenses have rendered technically flawless images routine, ubiquitous, even kind of boring. Now, it feels like each day brings a new and seemingly endless stream of pretty pictures. But how many of them actually have anything new to say?

I’m no fan of any of this. I never saw much point in venturing out into the wilderness to be alternately bossed around and cosseted by guides who were younger, smarter, and better looking than me. I still fancy myself tough enough to travel hard across most any wilderness. Besides, sleeping in the dirt and eating dismal camp food makes good practice for the day my wife, Janet, grows weary of these antics and changes the locks.

I have long dreamed of finding my own private Arctic bastion, unpeopled but well-stocked with polar bears. Since Northern winters are long and dark and bracingly cold, and what reading I’d done promised death by frostbite, scurvy, or starvation, I reckoned that a summer visit might be a more prudent starting point. I’d dip my toes into the shallow end of the survival pool. Polar bears winter on the Arctic icefields. Come summer, the midnight sun returns and nearly all of that ice melts away. Shouldn’t it be possible to take a small boat and visit the bears during those months as the ice disappears and the bears head for shore?

In the end, I found myself reluctantly following that well-worn tourist trail leading to Churchill after all. I couldn’t afford my own private Tundra Buggy, so if I wanted to go it alone some creativity was required. I decided to go BYOB—Bring Your Own Boat.

Starting with the purchase of an inflatable boat barely ten feet long and a small ten-horsepower outboard motor, I assembled a mountain of gear in my garage. I packed up layer upon layer of long underwear and weatherproof sailing gear, goggles and gloves, hats and boots. I stuffed cases with photographic and underwater equipment. I gathered camping and survival gear, a stove and weeks’ worth of dried camp food, satellite phones and beacons, and enough bear-banger noisemaking shells to hold my own Fourth of July fireworks show. Tree-hugging, liberal pretensions notwithstanding, I took a drive from my quiet Seattle neighborhood out past the Silver Dollar Casino and the adjacent Moneytree Payday Loans storefront, to Discount Gun Sales. There, after a scant background check and no training at all, I procured a Remington Model 870 Special Purpose Marine Magnum pump-action shotgun. I gingerly cradled the gleaming stainless steel twelve-gauge in my hands like it might explode at any moment. The gun, together with a box of matching twelve-gauge slugs, wicked thumb-sized pieces of lead, was to be my last desperate line of defense in case it all went terribly wrong. And if I did wake one night to discover my leg clamped in some polar bear’s jaws, whether I would shoot the offending bear or myself remained an open question.

I set off in my overloaded SUV, speeding east across half a continent’s worth of interstate highways. After four days’ travel I arrived at the pavement’s end, looking not unlike a homeless, survivalist hoarder. There, in Thompson, Manitoba, I swatted at black flies while piling everything onto the train heading north across the wilderness. When I finally decamped in Churchill, the calendar said it was late June, but all the same I was greeted with the cold, hard slap of rain whipping in off the pack ice. It was just me and that mountain of gear piled up on the platform as the train pulled slowly south.

A late thaw had left the shoreline jumbled with ice, great pans of it heaved up against the shore, a solid line of white disappearing into the fog. I had imagined myself camping in the Arctic wilderness, listening to the call of loons from my toasty sleeping bag. Here in the real world, I booked a room at the Polar Inn and overloaded a taxi to haul my crap the three blocks from train station to hotel front door. The management greeted me, my gear, and the trail of mud I tracked through the lobby with an air of bemused disbelief. Still, they lent me a pickup truck to carry the heaviest bits down to shore and I quickly set to work inflating my laughably puny boat with a too-small hand pump, puffing and muttering darkly against the chill wind. In the absence of a proper small boat harbor, I tied my dinghy to a big chunk of metal sticking out of the gravel beach and hoped for the best.

The truth was that I had no idea how any of this could end well. Small boat, big water, and aggrieved polar bears; it sounded like the recipe for grisly headline news. Other than a few local operators running tourists out for a cold swim with the beluga whales, there wasn’t much boat traffic on this stretch of Hudson Bay. The coastline was utterly flat and offered no protection from the storms that howled in off the land. The Bay itself might be better described as a vast inland sea, six hundred miles long and up to four hundred miles across. When the wind blew, there wasn’t a tree or hill in half a thousand miles to stop it.

I quickly discovered that Hudson Bay wielded a monstrous range of tides, the water dropping as much as thirty feet from high tide to low ebb. A quagmire of mudflats and slime-slick rocks circled the shore when the tide went out, creating a half-mile slog over which I had to haul my eighty-pound motor, then the seventy-five-pound boat, and all of those cases of heavy gear.

As soon as the wind dropped that first evening, I ventured out onto the water, nervously picking my way through the ice, scouring the horizon for some hint of a polar bear. It turned out to be really hard to find a solitary polar bear in an ocean full of ice—who knew? I spent hours staring at the floes, days motoring hundreds of miles through the melting pack. As I wound my way through the shifting maze, I stopped frequently, climbed up onto any high spot I could find on the ice, then slowly scanned the horizon with binoculars for the white-on-white outline of a bear. Venturing farther and farther from shore, I would stay out until the midnight sun dipped below the horizon, leaving me to navigate home by GPS and the distant, twinkling lights of town.

After two weeks of toe-numbing cold, summer suddenly arrived on the heels of a dark line of thunderstorms. Clouds of biting black flies and mosquitoes descended as temperatures spiked into the nineties. At least I had something new to complain about. A strange haze—smoke from distant forest fires—filled the sky, drifting in with the record heat. Once the storms blew through, I set out from shore again, and spent an hour motoring hard to reach the melting ice. In the orange half-light, every lump and hummock looked like a bear. Hours passed. From a crumbled snow-covered ridge, I looked, and then looked again, and—to my astonishment—saw movement. A half mile away, a young bear woke and quickly shambled from the ice off toward water.

Polar bears are creatures of the sea. Classified as marine mammals, they spend most of their lives on the ice or in the ocean. It’s only during the lengthening summer thaw that they spend appreciable time on land. When surprised, a bear’s first reaction is often to head to the safety of water. Sliding ass-first off my own iceberg, I hopped into my boat and set off, struggling to keep the bear in sight.

Though possessed of a fearsome reputation, most bears will often as not avoid human contact when they can. Bears near town are hazed with noisemakers and beanbag shotgun shells. The overcurious are darted with tranquilizers and may spend months caged by local wildlife officials until freeze-up. Repeat offenders are not infrequently shot dead. Of course, should you find yourself alone in the wilderness, your attention wandering, and you stumble upon a polar bear feeling particularly unfastidious, you may find yourself among the hunted. Most bears will steer a wide berth, but this one, a young female judging by her size and build, gradually calmed and began to grow curious as I slowly trailed her. We were soon moving through the water in tandem, separated by a hundred yards, then fifty, then—holy shit, that bear was really close.

I dumped my camera gear out of its waterproof cases and shot her with the works. Telephoto lens. Wide-angle lens. Underwater pictures with a housing and fisheye lens. I held the outboard’s throttle and steered the boat with one hand while shooting with the other. I even mounted one camera onto a six-foot boom and then awkwardly tried to swing it closer to her, but succeeded only in dunking the contraption into salt water, killing the camera, lens, and trigger.

Undeterred, I dug out a spare camera and began chewing the insulation off a copper wire to jury-rig a replacement shutter cord. As the bear swam beneath an iceberg, I managed to drift the boat in closer and hang the boom beside a hole in the ice. She rose to breathe and I began shooting, blindly pressing the shutter cable and hoping that something, anything, might be in focus. She submerged for a moment, then surfaced again for one more breath before disappearing beneath the ice.

The midnight sun hung like a dying star in the hazy orange sky. The bear reappeared and paddled slowly toward the sunset on a sea glowing like molten metal. I followed at a distance, utterly transfixed, listening to her steady breathing and watching as her powerful front paws stroked through cold ocean. Stillness fell upon the water. There was no land in sight. I was alone at sea with a polar bear. The moment felt like I had been given a perfect jewel, something precious to hold onto for the rest of my days. I could have followed that bear for hours through the short half-lit summer dusk. But I cut the engine and let the boat drift. I watched in silence as she swam away, a slow vanishing.

I sat for a long while, the scene burning into memory. But I was still more than thirty miles from shore, and darkness was gathering. I pulled the outboard’s starter cord, felt the motor catch, and steered my boat toward shore.

On the southbound train a week later, I sorted through the photographs on my laptop. There was my bear, walking across the ice, swimming and diving. Suddenly, there it was: one magical image that I’d never seen before, nor imagined, not even in dreams. In it, the polar bear floats beneath the surface, staring back up at my camera, surrounded by ice and empty sea, lit by the burnished, hazy sun. I laughed out loud, then started parading up and down through the passenger cars like some lunatic, showing the picture to a trainload of complete strangers.

I was hooked. I knew I had to come back and tell the story of this wild, lonesome, and dangerous place. More than anything, I was obsessed with finding more photographs that might again capture and illuminate and somehow hold on to the spirit of the ice bear.

Submerged polar bear beneath melting sea ice, thirty miles north of Churchill, Manitoba

Irma Zug and Zembo Shrine Masonic Lodge tour group, Honolulu Airport, circa 1964 (photo by Paul D. Zug)

Paul Souders at age six, Pennsylvania, 1967 (photo by Irma R. Zug)