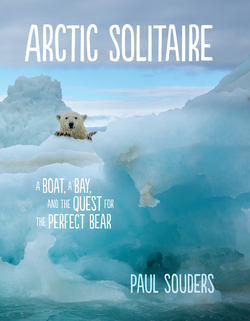

Читать книгу Arctic Solitaire - Paul Souders - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 8 BIG WATER

ОглавлениеI was up before the sun. Halfway through July at this northern latitude, that meant crawling out of a perfectly warm sleeping bag somewhere shy of four in the morning. The sky was flawless and beautiful: pink to the northeast, deep blue overhead, with a line of dark indigo, the last shadow of night, falling away toward the western horizon.

Forty-five miles and eight hours later, I arrived back at Cape Tatnam, already starting to worry about my fuel situation. I was still more than 150 miles from the nearest gas station in Churchill. Leaving only the slimmest margin of safety, I needed forty gallons to get there. That left only eight, maybe ten, gallons to spare as I headed east on the hunt for ice and bears. If I used my light Zodiac and its small outboard motor, I could cover a lot more ground while burning far less fuel.

The sun felt warm, and the last few days’ rains had discouraged the forest fires that were raging beyond the Cape.

I let the anchor out in thirty feet of water and again packed my cameras and survival gear into the small dinghy. I bounded off across the open water, trying not to dwell on the emptiness that surrounded me. I found ice after an hour of steady motoring, and made a mental note to haul some of it back to C-Sick to keep my dwindling beer supply properly chilled.

From the dinghy, I glassed all the different shapes and contours of the melting sea ice looking for any sign of polar bears, but from down at sea level I could see next to nothing. I gunned the engine and popped the dinghy’s nose up onto a large, flat iceberg, then gingerly stepped off and climbed a low hummock. I slowly, methodically scanned the horizon again with the advantage of ten feet of elevation. Nada.

I wish I could say I was the Bear Whisperer, that I possessed a secret communion with polar bears—some Zen mastery that allowed me to see the bear even before I saw the bear. Or that I could send a whisper out upon the wind, carried from my chapped lips to fuzzy ursine ears. If there is a secret to finding a white bear in an infinite field of white ice, nobody has shared it with me. Out here, it was simply a matter of grim determination: scanning every stinking piece of ice for hour after hour with weighty, overpriced Teutonic binoculars glued to my eye sockets. And still, nothing.

I’m apparently not the only one to have trouble finding and tracking these bears. Studying polar bear numbers and population trends has always been a difficult, expensive, and inexact proposition. Biologists have spent decades trying to accurately count these well-camouflaged and nomadic animals across hundreds of thousands of square miles of ice, but the numbers still sound more like vague guesses than hard scientific fact. A 2011 aerial survey put the number of bears along the western Hudson Bay’s shores at just over one thousand, and there may be as many as two thousand more living farther north, in the Foxe Basin beyond the Arctic Circle. Though the population numbers appear more or less stable, studies have measured a direct correlation between dwindling sea ice conditions and lower body weights for female polar bears, along with poorer survival rates among their young cubs.

When the sun finally dipped below the horizon, the air chilled, and I pointed the Zodiac back toward C-Sick. As I reached forward to drain the last drops of hot cocoa out of my thermos, I leaned too far and accidentally pulled out the safety lanyard. It was there to stop the engine should I happen to fall overboard and prevent the unhappy prospect of finding myself bobbing cold and alone in the icy waters as my dinghy motored on toward distant shores without me. The kill switch did its job admirably. So much so that the engine could not be persuaded to start again, no matter how hard I yanked on the rope. I was still ten miles out from C-Sick. Pull. Mutter. Wait. Pull. Worry. Wait. Pull. PULL PULL PULL PULL! Oh fucking hell.

Fireweed and setting midnight sun, Hubbard Point

One minute passed. Two minutes. I sat and tried to calm my breathing. Then pulled again. Finally. The engine caught but I set out again feeling deflated and overmatched. My gear wasn’t good enough for this trip.

Hell, I was not good enough to be so far out past the edge.

At long last, I made it back to the shelter of C-Sick, curled into my sleeping bag, and fell into a deep sleep. There was just enough tide, wind, and current to send the boat rocking on her anchor. I dreamed, not of flying, but of a sort of low-gravity soaring walk down some strange sidewalk. I imagined floating up and gliding impossibly far with each step. It’s a dream I have only on boats, only when the world is rolling beneath me.

When I first imagined this trip, I expected to arrive at the ice edge, tie up to some convenient berg, then drift along for many happy and bear-filled days. As I looked around at the endless expanse of water, the notion seemed laughable. My inner voice of reason—along with its ugly second cousin, chickenshit cowardice—shouted down any talk of death or glory. I looked at my drained fuel tanks then looked at the charts and knew that it was time to move on. I danced the points of my nautical calipers end over end until I measured the distance to Cape Churchill. It was 113 miles, and thirty more to reach town. All in all, the better part of twenty hours’ travel.

I set off and motored for hours on a northwest course through the middle of a flat, infinite plane, the sea calm, like a pool of liquid metal, reaching away toward infinity. By evening, distant forest fire haze turned the sun into a copper penny orb and a breeze began to stir, building choppy waves. I pushed on until nearly midnight, then shut down the engines and let the boat drift. I was desperate for sleep, but every time I dozed off, C-Sick