Читать книгу Arctic Solitaire - Paul Souders - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 5 A HOLE IN THE WATER

ОглавлениеThis might be a good time to point out that I hate boats.

I hate the smell of them. I hate the cloying dampness, the sea-sickening bobbing-cork lurch, and the musty, cramped spaces. Then there’s the unmistakable correlation between time on the high seas and violent psychological disorder. I’m hardly the first to observe that life at sea offers all the benefits of prison time—with arguably worse company and distinctly better odds of drowning.

Yet even as my brain and my accountant shouted, No, no, no, my heart said, Oh hell yeah. It was time for a proper boat. I already had plenty of experience bashing around the waters of Alaska, Canada, and Greenland in small and often leaky Zodiac dinghies. These were not much more than blow-up rafts with an outboard motor bolted on the back. Light enough to carry as airplane luggage, once inflated, they could carry thirty gallons of fuel, weeks’ worth of food, and all the camera gear I was willing to destroy. I covered thousands of miles of remote wilderness coastline in those boats, and felt like I was cheating death at every turn.

Picture the elegant simplicity of paddling a sea kayak across the still waters of some wondrous coastal fjord. Now imagine the exact opposite. Riding in a Zodiac can best be described as neck-snapping, molar-shattering torment. Every ripple, bump, and wave on the water is amplified up the length of your spinal column. There’s no avoiding every drop of rain sent down from heaven nor the torrents of salt spray tossed up by the sea. Then, at the end of a long day’s watery travels, there remained the prospect of locating a suitable campsite, wrestling a soggy tent into submission, rehydrating a bag of freeze-dried cardboard over a hissing camp stove, and settling in for another cozy night’s sleep in the wet dirt, keeping one ear cocked for the sound of approaching bears.

For years, I jealously watched big cabin cruisers motoring up and down Alaska’s Inside Passage as I squelched around the forest. From my dismal perch, I could watch proper yachting couples traveling in leather-upholstered splendor, sipping cocktails and preparing freshly caught salmon in their stainless steel galleys, before they settled down to eat by the warm glow of generator-powered lights. More than once, as I sat shivering in my dinghy, a stranger motored past and asked where my boat was. What could I say but, “You’re looking at it”? If I sniffled and looked suitably pathetic, I could usually wheedle a cup of hot chocolate out of them.

Yet for all the months and miles I’d spent on the water, I didn’t know much about proper boating that I hadn’t picked up from Jacques Cousteau. On Sunday nights at seven thirty. I couldn’t change a spark plug or tie a proper knot or fix a leak, and I was not above navigating with the torn-out pages of a road atlas. Still, I felt smarter than the kayaker I once passed in Alaska’s Kenai Fjords who was using the cartoon map printed on some fish-and-chips joint’s souvenir placemat.

After a decade of Zodiacs, the novelty had worn thin, even as my obsession with the North grew more fevered. I sometimes wonder how life would have turned out if my early reading hadn’t inclined so heavily toward Never Cry Wolf, Arctic Dreams, and their frostbitten literary kin; if I had directed my creative passions more in the direction of swaying palms, warm breezes, and lissome tropical maidens wearing come-hither looks and not much else. If I’d pursued a life less Call of the Wild and more “Margaritaville.” But I was raised Lutheran, and the gray-bearded God of my youth expected us to be brave, work hard, and leave the sun-soaked beaches for more fun-loving folk.

When I found myself with some money to squander, I went out boat shopping. It was more dumb luck than rigorous research that led me to the C-Dory boats. Built just outside Seattle, these rugged fiberglass cabin cruisers were designed for weekend fishing trips around the sheltered waters of Puget Sound. They were small enough—eight-and-a-half feet wide, and twenty-two feet long—to haul on a trailer, but came equipped with a rudimentary bed, table, and kitchen. They reminded me of my old VW camper: simple and functional, but less inclined to leave me stranded with a dropped transmission in the middle of the New Mexico desert.

I bought the first boat I set eyes on. The owner, Pastor Kirby, had christened her “C-Sick”—that’s Lutheran humor for you. He let me take her out for a white-knuckle test drive on Puget Sound. That I didn’t sink the boat and drown us both I attribute to the power of his silent, fervent prayers. He carefully explained that she was in pristine condition, with low hours and two spotless Honda outboard engines. I half expected the good pastor to tell me he’d only driven her to church on Sundays. I was a fish on the hook; he barely had to reel me in. I paid full asking price, far more than she was worth, but you can’t stop love.

The C-Dory seemed to me the personification of a Maine lobsterman’s boat that had been softened by years of boring office work and life’s heavy burdens—a mortgage, maybe some child support—but still tried to keep up with the old gang out on the water every weekend. Inside, her low forward cuddy cabin featured a cushioned V-berth, just big enough for two adults on intimate terms to sleep toe-to-toe beneath a fiberglass ceiling eighteen inches above their heads. The main cabin was taller, with more than six feet of headroom. It was a tight space all the same. I could stretch out my arms and touch the side walls, and it was three short steps—or two long ones when I was scared—from the simple gray-cushioned captain’s chair to the cabin door, where I’d find whatever fresh trouble awaited me on the back deck.

Her builders had managed to fit all the necessities of shelter within this space: a combination two-burner stove and heater, and an eighteen-gallon freshwater tank that fed the stainless steel sink and faucet through a small foot pump. The thirty-inch Formica table dropped down to fit between two simple bench seats and created an austere sleeping berth. She had a tiny icebox big enough for a couple six-packs under the captain’s chair, plus more storage under the seats and beneath the galley sink. She came with a tiny, portable flush toilet crammed in behind a privacy curtain, that I replaced, in a fit of Luddite primitivism, with a simple five-gallon bucket.

At the helm, her original instruments were sparse but seemed to cover the essentials. a decade-old GPS with local charts, and a vintage fish-finder that measured depth as illustrated by crude, pixelated images of the fish purportedly swimming in the waters below. There was a marine band radio, a radar display that I neither understood nor trusted, some switches for the cabin and running lights, and a bigger switch to haul up the anchor. There was even a drink holder, sized to the exact dimensions of a beer can.

Pastor Kirby had outfitted the boat with a new canvas enclosure that turned the open rear cockpit into an extension of the cabin’s modest living space. I dismissed this as mere frippery and promptly unbolted the thing. It sat neglected in my basement until I had endured a suitable number of cold, rain-drenched months in Alaska watching the open cockpit fill with water. When I finally relented and bolted the canvas back into place, C-Sick’s usable space was effectively doubled. Its clear plastic windows revealed all the scenic wonder with none of the steady trickle of ice water running down my neck.

Fully laden, the boat required a bare three feet of water to float—closer to two feet if I was quick enough to hit the hydraulic lift that pivoted her engine propellers up and away from danger. Modeled in part on old fishing dories, her bottom was nearly flat. Throttle open, C-Sick flew across flat water like a skipping stone, but when the wind kicked up, she transmitted and amplified every ripple and wave.

Pastor Kirby, always prudent, recommended running the engines around fifteen miles per hour or thirteen knots. I have always been more of a full-throttle guy, but as soon as I signed the papers, I recognized that this was a lot more boat than anything I’d had keys to before. I was now responsible for a young life, precious and fragile: C-Sick’s, at least, if not my own.

One of the many wonderful things about America is that you’re free to buy any boat the bank is dumb enough to finance and, without a lick of training, head out onto the wide-open ocean to kill yourself and any other fool who steps aboard.

In an uncharacteristic moment of foresight, I signed up for a Power Boating for Complete Morons class down at the marina. I learned the basic rules of the sea, docking and navigation techniques, and some of the simpler forms of maritime suicide prevention. One lesson the course thoughtlessly omitted was how to back a fully laden trailer down a boat ramp while enduring the jeers and taunts of any nearby drunken fishermen. After fifty or sixty tries, I just about got the hang of it, but my palms turn sweaty every time I think back to those humiliating spectacles.

That first summer exploring the wild corners of the Alaska coastline, I quickly learned that boating exists in a gray zone between life as an unemployed grad school dropout and formally joining the ranks of the homeless. I might not bathe for a week. I crapped in a bucket, slept on a fold-out sofa, drank alone and to excess, and compulsively talked to myself—all while trying to avoid the watchful eye of law enforcement personnel. I finally began to understand why married men, grown weary of the responsibilities and comforts of their domestic routine, go fishing. I’ll give you a hint: it’s not about the fish.

Barreling along with the throttle open and both engines roaring, I covered nearly more than four thousand nautical miles that first summer. It turns out knowing fuck-all about boats is not the hindrance you might expect. When I dinged a propeller on the rocks, I figured out how to unbolt the mangled prop and slap on a new one while hanging over the transom, after only fifteen minutes of vigorous upside-down swearing. When I misread the tide charts during a shore excursion, and returned to find C-Sick sitting high and dry amidst the starfish and sea urchins, I trudged across the squishy tidal mudflats, climbed back aboard, and as punishment watched The Perfect Storm for the third time on my laptop until the tide came back up and we floated free. As long as no one was watching, I was content to work my way slowly, if expensively, up the nautical learning curve.

For the next several summers, I returned with C-Sick to photograph the length of the Southeast Alaska panhandle, then worked up the nerve to take her from Kodiak Island out to the forbidding Alaska Peninsula and storm-swept waters of Katmai National Park. I followed in “Grizzly Man” Timothy Treadwell’s erratic and doomed footsteps, walking among dozens of brown bears for months at a stretch. But the bears didn’t scare me half as much as the howling storms and murderous forty-mile open water crossings. I still remember some old coot of a bush pilot looking out at my boat and shaking his head in disgust, muttering, “You’re gonna die cold and alone out here, boy. Cold and alone.”

Maybe, old timer. But not just yet.

In between my solo boat trips aboard C-Sick, I also chartered proper expedition sailboats, steel-hulled seagoing yachts, to take more ambitious high-latitude trips; south to see penguins in the Antarctic and a couple times up to Norway’s Svalbard archipelago, near eighty degrees north latitude. I wanted to photograph polar bears and the barren, Arctic landscape. The place was otherworldly, halfway between the top of Europe and the North Pole—stark, frightening, and breathtaking in its austere beauty. It was also not cheap. The boat charter alone cost more than $25,000, on top of the extortionate costs of plane tickets, food, and the abundant stocks of liquor required to maintain the skipper’s good humor. Even during the photo industry’s flush years, I could never afford a three-week charter on my own, so I cast a wide net and dragged along anyone who could pay. A few even remained friends after the yelling was over. Others, well, there is no enemy quite like the one you make on a cold, cramped boat in the middle of nowhere, with no possible escape from each other. I will accept much of the blame. I know that I can be difficult.

For all my faults, though, laziness is not among them. I had come to photograph polar bears, and photograph polar bears I did. I would stand on deck in the cold wind for hour after toe-numbing, finger-freezing hour, doggedly scanning the ice. I adopted my best steely-eyed, thousand-yard stare, feet apart, and scanned the ice through a pair of bulky and overpriced German binoculars. When I finally spotted my quarry, I notified the skipper with a curt flick of my chin to show our new course, and say simply, “Bear.”

No wonder everyone hated me.

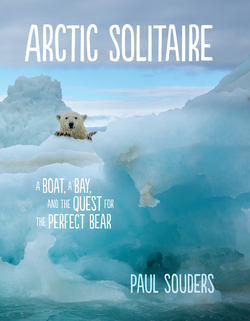

Before I found myself set adrift on some lonely iceberg by mutinous shipmates, I needed to find another way. I turned to C-Sick. I imagined that if I could take her north, I might see polar bears on my own terms, living among them for weeks or months at time, with no one else around to complain about my personality quirks, poor hygiene, or wretched cooking. It would be just me, C-Sick, and the bears.