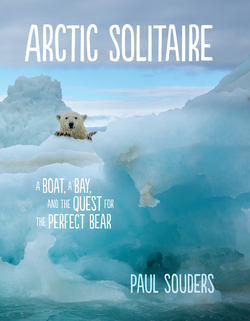

Читать книгу Arctic Solitaire - Paul Souders - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 7 THE RIVER AND THE BAY

ОглавлениеThe wilderness was vast and seemingly empty, but as I motored along I was nestled in a glowing cocoon of technological magic. Not one but two Garmin GPS chartplotters silently communed with the satellites overhead. My radar system could penetrate the thickest of fogs, though the day’s clear skies and sunshine made the prospect unlikely. My depth-sounder pinged sonar pulses off the rocks below, and I even carried something called, in bureaucratese, an Emergency Position Indicating Rescue Beacon, or, more jauntily, an EPIRB. Supposedly it would, at the panicked touch of a button, supply my coordinates and credit card information to the nearest helicopter rescue service.

I may not have known what I was doing, but I could tell you exactly where I was doing it.

Later in my travels, I would encounter a number of Inuit who would sagely tap the side of their heads and say, “My GPS is right up here.” To be sure, I admire anyone who can find their way through the wilderness unaided by modern technology. Then again, growing up in white-trash Pennsylvania, I could usually find my way home just by following the smell of chickenshit and the trail of broken beer bottles. But out here at the ass end of nowhere, I was always one blown fuse or dead battery away from becoming an Arctic version of Tom Hanks’ character in Cast Away, without the coconuts or the volleyball.

C-Sick at anchor, Marble Island, Nunavut Territory

Even with all this technology, the way forward seemed little more than guesswork. I quickly discovered my fancy electronic charts displayed nothing about the Nelson River this far inland, and I hadn’t thought to bring along a topographical map that might show the river’s contours. Aside from the twenty-foot-high banks, there wasn’t much in the way of topography, anyway—just hundreds of miles of flat, buggy forest that eventually gave way to flat, buggy tundra.

I motored along blindly, using my depth-sounder to steer clear of submerged rocks and the irregular shelves of hard granite, invisible in the milky green water. Every time I passed over a shallow spot, I unconsciously held my breath and lifted my feet off the floor, as if that was going to help.

When I reached the deeper main channel, a strong current swept C-Sick downriver. I was soon traveling at more than nine knots, nearly eleven miles per hour, with my engines hardly ticking above an idle. There was no turning back. I couldn’t fight my way back upriver against this current even if I wanted to. Like it or not, I was on this ride to the end, seventy-five miles to the Bay and whatever came after. I let go of that unhelpful thought and settled in as best I could, relaxing enough to enjoy the warm sun and a gentle breeze blowing upriver. It occurred to me that I should remember this feeling—the beginning-ness of it. Lost in the swirl of planning and motion and action, I had spent weeks plunging blindly ahead without ever taking time to appreciate the moments as they passed. I took out my cameras and shot a few desultory frames to record the scene. Silty river, sky of blue, forest green. But for the most part I simply basked in the fleeting minutes when I might finally breathe in and out and slow the passage of time.

From a distance, the spindly spruce forest and dense carpet of moss atop crumbling riverbanks looked almost inviting, like something out of a fairy tale, if you could ignore the swarms of biting and blood-sucking insects. Where fires had swept through, stands of dead, sun-bleached trees stood straight as toothpicks along the river. I counted a half-dozen bald eagles, along with scores of Bonaparte’s gulls and Arctic terns, diving for fish in the swirling rapids.

Gradually the river grew wider. In the late afternoon, I rounded a bend and suddenly the steep banks and endless green forest gave way to . . . nothing. Off in the distance, I could just make out the featureless horizon, and beyond it, the Bay.

I laughed out loud. It was all going to be okay, after all.

And then, it wasn’t. The depth-sounder shallowed suddenly from ten feet to eight, and then five. I let myself be distracted by some rattle behind me and, as I turned around; the first sickening crunch of rock against boat. I scrambled to get my engines up without tearing off the propellers, but the current had me. C-Sick slammed into barely submerged rocks again and again, making a horrible grinding sound. When the music finally stopped, I was well and truly grounded.

On the bright side, I was unlikely to either sink or drown in less than two feet of water. The bad news was that we were stuck at least fifty river miles from another living soul. My big Arctic expedition ground to a humiliating halt before I even reached salt water.

If there was an instruction book for this sort of mess, I’d never seen it. Improvising, I started offloading sixty gallons’ worth of extra fuel cans into the Zodiac I trailed behind C-Sick. Then I chucked in the heaviest camera and food cases on top. After that, I hopped over the side into the river shallows and began shouldering C-Sick with all my strength. I managed to get her off the rocks and scrambled back on board before she had a chance to drift out of reach. I didn’t have time to celebrate, because she quickly grounded again. The next two hours devolved into a slow-motion nightmare: too many rocks and not nearly enough water. I tasted the rat-breath slick of desperation in my mouth as I struggled to float more than a hundred yards at a go before fetching back up on the rocks.

At one point, having floated C-Sick free, I strung the boat along by a rope tied to her bow, leading her through knee-deep water like a reluctant dog. Up ahead, I could see a group of seals swimming upstream. I climbed aboard to grab a camera, only to realize that the seals were really just more rocks sticking out of the fast-flowing current. The sun dropped slowly behind thickly forested hills. It was hours later and nearly dark before I found enough deep water to restart the engines. I painstakingly picked my way into the lee of two small islands and finally dropped anchor with less than ten feet of river beneath me.

My anchor was sixteen pounds of tensile steel shaped like a three-toed claw and designed to bury itself in the muddy river bottom. It was secured to fifty feet of galvanized steel chain that was, in turn, spliced on to 150 feet of 5/8” three-strand nylon rope, and finally attached to a reinforced U-bolt through C-Sick’s hull. After I bought it, I found a spec sheet that said the anchor chain and line, called a rode by the nautically inclined, should withstand 8,910 pounds before breaking. I wondered uneasily who was in charge of testing that. I hoped it wasn’t some college kid whose dad got him the job for the summer.

In theory, you could lift C-Sick out of the water and hang her up to dry by that anchor. I did know it had once held through eighty-knot williwaws that came howling out of the Alaska Range, kicking up a wall of white spray before nearly capsizing C-Sick.

At eleven p.m., the last light of day colored high cirrus clouds salmon and blue. This far north, the sky was still too bright for stars. I poured a dram of Irish whiskey to settle my frayed nerves and stepped outside to brave the mosquitoes out on the back deck. I raised a toast to absent friends, thanking them each by name as I pictured their faces, one by one.

I poured the last thimble of my drink onto the river’s swirling surface, a small offering. I hoped it might reach the Bay and mollify its irascible gods. The whiskey was gone in an instant, swept toward the vast sea looming ahead.

That night I woke repeatedly to check the anchor’s hold. In the three a.m. half-darkness, I looked up and smiled at the familiar sight of the Northern Cross as a pale band of aurora arched overhead.

At dawn, C-Sick’s GPS display showed us anchored somewhere up in the forest, hundreds of yards away from the river, a discovery that further eroded my already shaky confidence. I lowered one of the two outboard engines into the water, reserving the other in case I tore up the prop, and began to slowly nose my way into deeper water along the Nelson River’s main channel. In the distance, I could make out the abandoned train trestles left nearly a century before at Port Nelson. Early shipping magnates dreamed of a shortcut rail and ocean link between the prairie wheat fields and British and European markets. They pushed a railroad north across hundreds of miles of boggy forest, all the way to the Bay’s shores, then built a shipping terminal there. Boosters loudly and unironically proclaimed in The Hudson Bay Road that the Bay would soon be “the Mediterranean of the North.” During the port’s brief time in operation, three ships sank in four short years, and the business collapsed with the start of the First World War. A hundred winters of river ice had shattered the bridges’ timbers, and the rusted tracks now hung twisted and looked ready to topple into the water below. One of those shipwrecks was still there, hulking and rusted, lying half-submerged just offshore. I find there is nothing quite like a grand spectacle of ruin and costly failure to shine the harsh light of perspective on my own fragile dreams.

I tempted fate with a playful slalom run through the old trestles, taking snapshots and wondering when the whole thing might crumble down on my head. Then, I headed out into the Nelson River’s wide delta. I timed my departure out into Hudson Bay to take advantage of the ten-foot outgoing tide, hoping to ride its current away from the braided shallows and into deeper salt water. What I didn’t anticipate was an opposing east wind blowing in off the Bay. One minute I was traveling at nine knots over calm seas; the next instant, I was slamming into steep, standing waves. Cresting a three-foot roller, C-Sick pitched over hard and I heard a dismaying crash from overhead. I had started this trip with a large cargo rack bolted on top of C-Sick’s cabin. It was a last-minute addition, to store lightweight but bulky supplies like toilet paper, my bear fence, and some empty fuel cans. Now it was upside down and floating away across the Bay.

I considered letting the damn thing go, but this would be a long trip without toilet paper. With a torrent of swearing and one-false-move-andyou’re-in-the-water grappling, I wrestled the cargo box onboard, soaking myself as gallons of seawater poured out of it. I had long imagined the moment when I would finally reach Hudson Bay: it would mark a huge milestone and should have been a moment of celebration. As it was, I was too busy squeezing seawater from my eighteen-pack of toilet paper to much notice. By the time I bolted the cargo box back in place and lashed it down with a couple heavy cargo straps, I was breathless and furious and soaked to the skin.

Hudson Bay covers nearly half a million square miles, and is connected by a narrow, tide-swept strait eastward to the Atlantic. There is an even more tortured and ice-blocked path to the west, via Fury and Terror Strait through the Northwest Passage and on to the Arctic and Pacific Oceans. The Bay’s waters begin to freeze in early November, and do not thaw again until the long hours of daylight return in June and July. The last remnants of ice sometimes linger late into the summer months. These patterns change with the vagaries of each year’s weather, but more than a century’s worth of statistics show that a rapidly warming climate has left more open water for longer periods through the summer.

Environment Canada posts ice charts each day on its website, and I had been obsessively watching the winter ice’s melt for weeks. As I prepared for my departure, I grew worried, then dismayed. All the ice along the Bay’s west coast, between the Nelson River delta and Churchill, had melted weeks earlier than usual. The satellite maps now showed only a few icy remnants floating out far to the northeast of the Nelson’s mouth. I had many miles to go before I might find enough ice to chill my evening cocktail, let alone support any polar bears.

My destination for the day was Cape Tatnam, still fifty nautical miles off. The C-Dory was designed as a speedboat; its twin forty-horsepower outboard motors could send a lightly loaded boat skipping along at more than twenty-five knots. She came from the factory with two twenty-gallon gas tanks, which, used carefully, might propel the boat for 150 miles. As my trips grew more ambitious over the years, I accumulated a stock of six-gallon plastic cans that soon filled every available space on deck. I kept the leaky red containers held in place with a tangle of bungee cords and ratchet straps. C-Sick now carried more than one hundred gallons of fuel, weighing close to six hundred pounds, and my woefully overloaded boat sat low in the water. Add to that hundreds more pounds of camera equipment, survival equipment, and food—and the additional burden of sodden toilet paper on the roof. If I had to, I could push the boat up to twelve or maybe fifteen knots, but as I bumped up the speed, the engines would use exponentially more fuel. My plan was to go slow. At a leisurely pace of five or six knots, I burned a single gallon per hour, and could travel as much as five hundred nautical miles before I would need to start paddling.

Soon, I felt like I really was at sea. Port Nelson slipped beneath the horizon, and I traveled miles offshore to avoid the mudflats and shoals that stretched far out into Hudson Bay. Only a faint line of refracted, distorted forest marked the shoreline far to the south. There was nothing but sea all around and a flawless blue dome of sky above.

Along this part of the Bay, I never saw another boat. Or ship or barge or skiff or raft, either. Except for a few jet contrails far overhead, I might have been the last man on Earth. As hours passed, I began to feel a vague anxiety growing beneath the burden of the vast and featureless expanse. I felt every one of the six hundred open miles of ocean to the north like a weight teetering above my head, ready to come crashing down with the next storm. I didn’t even know where I was going to anchor that night. Not that it mattered, really; there wasn’t an island or a natural harbor or the slightest hint of shelter where I was headed.

Clouds of black and common scoters wheeled and turned in the coloring sky as the sun slid from the western horizon toward north. I could find not a hint of the promised sea ice. Instead, a forest fire billowed smoke from beyond the tidal flats.

I tried not to think about the fickle weather or how utterly exposed I was, five miles out from shore and ten times that far from shelter. Hours later, when I dropped anchor at sunset, the evening breeze calmed. The Bay went still: a steely blue pool, shimmering and magical. I climbed up onto the roof, and stared out at the water stretching to the horizon in every direction. I felt smaller than a dust speck floating on this endless sea. From my starting point on the Nelson that morning, I’d covered seventy nautical miles. A good day’s work.

I woke to the smell of smoke—never a good sign, especially on a small boat. I bolted upright and stared wildly around, but was greeted not by flames, but instead by a thick white haze of forest fire smoke borne on the wind. A short night’s sleep had left me punchy and a little slow out of the gate. I wanted to run the Zodiac out to where I thought I might find the pack ice, and I set off heading due west. I motored along for several sleepy miles before it slowly dawned on me: I was heading the entirely wrong direction, and away from the ice. I swung the dinghy around 180 degrees, back the way I came and into what I thought was a line of morning fog. But in an instant, I was coughing and rubbing tears from my stinging eyes. I was motoring blindly along through clouds thick with yet more wood smoke.

Melting sea ice and distant forest fire, Cape Tatnam, Hudson Bay

I traveled nearly two hours away from C-Sick before I spotted my first pieces of ice. It was twenty miles more before I reached the edge of the pack. I spent the next few hours studying mile after mile of dirty, broken ice. No polar bears, just the disconcerting sight of distant trees burning in the summer heat, billowing plumes of smoke, and ice melting away before my eyes. Soon, the Bay’s mood began to darken, and an easterly wind started to build. I turned the Zodiac back toward C-Sick, but before long I was struggling to muscle the inflatable dinghy up the back of tall waves. At each crest, we pitched forward over the top, crashing down into the trough below. I fought to keep the boat balanced, hold everything onboard, and not panic. I continually checked and re-checked my handheld GPS to make sure I was on the right course. Without that small battery-powered device, I never could have found C-Sick, not in a week of looking.

She was right where I left her, though now bucking angrily at anchor in the waves. I had no stomach for sitting out a storm in these conditions. I scrambled back onboard and didn’t even change my sopping clothes before turning C-Sick west to ride the following seas back toward the Nelson River. The abandoned Hudson’s Bay Company settlement at York Factory, forty-five miles southwest, offered a sheltered spot to anchor inside the protection of the Hayes River. I motored C-Sick for eight or nine hours, picking up speed each time the boat surfed down the face of a wave. At sunset, we reached the river delta’s confusion of mudflats and unmarked, indistinct channels. I was desperate not to get stuck out on the flats on a quickly falling tide. As soon as I found more than four feet of water, I let out the anchor with a feeling of resignation and disgust. I’d been on the road for more than a week and had yet to accomplish anything. I may have been taking pictures all along, but they were nothing but snapshots—unexceptional and unmemorable.

During the night, I woke to raindrops pattering in through my open window, and I looked out on a flat, gray sky. Come morning, there was enough east wind to keep me hunkered down. But by afternoon, I was itching to get off the boat. I hadn’t set foot on land in four days, and I headed out to explore the abandoned site of York Factory. The settlement dates back to the late 1600s, when the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC for short, or simply and ominously The Company) established one of its first trading posts there, part of a centuries-long dominion over the northern Canadian wilderness. The small fort grew into the central operating base for its trade in furs and nearly every other facet of the frontier economy. Every year, nearly all of the trade goods that arrived—everything from casks of cheap liquor to cotton and wool fabric to knives, axes, and rifles—were off-loaded from the HBC’s ships. The empty holds were quickly filled with the new continent’s bounty: beaver and lynx, marten and wolverine, even polar bear and wolves were all trapped, killed, skinned, then bundled and stacked like cordwood and shipped back to England. For centuries, the HBC served as the de facto government across the Bay’s vast watershed—the sole employer and its only store. The Company effectively ruled 1.5 million square miles of land, nearly half of what is now Canada. For centuries, York Factory’s central location at the mouth of the Hayes and Nelson watersheds allowed canoes to probe deep into the continent’s heart before the invention of steam-powered ships and trains. In time, HBC traders ventured north to the Arctic Ocean and west to the Pacific by river, lake, and overland portage.

The Company introduced white man’s goods, weapons, and liquor to Native tribes unprepared for the oncoming rush of modernity. And York Factory, stuck out along the desolate southern shores of Hudson Bay, was at the center of it all. At its peak, halfway through the nineteenth century, there were fifty buildings, a permanent administrative workforce, and an even larger population of Cree and other First Nations tribes nearby, working and trading on the fringes of the new economy. Not everyone was a fan of the place, even then. Peter Newman’s sprawling book Empire of the Bay describes one clerk who, having endured the winter of 1846 here, grumbled that it was “a monstrous blot on a swampy spot, with a partial view of the frozen sea.” The place wore down even the toughest Scots—men like James Hargraves, who served for years as an administrative chief, or factor in Company parlance. Plagued by rheumatism, he complained bitterly that the local climate was “nine months of winter varied by three of rain and mosquitoes.”

The Hudson’s Bay Company story is likely familiar to anyone who has cracked a history book. The unquenchable hunger for pelts nearly wiped out the beaver and decimated just about anything else unlucky enough to walk on four legs and wear a coat of fur. Vast fortunes accrued in London even as disease and dissipation shredded the fabric of indigenous tribal life. It wasn’t until 1870 that the newly formed Dominion of Canada gained sovereignty over what had been a private HBC fiefdom across the Northwest Territories. Developing rail and shipping links farther south rendered York Factory largely irrelevant, its once central location now increasingly remote from the new markets and distribution centers. It struggled on, a shadow of its former glory, until 1929 when a new narrow-gauge railroad connected Churchill to the outside world. The facility fell into disuse and the last of the big ships sailed in 1931. The fort closed for good in 1957 and the few surviving buildings were handed over to Parks Canada. The whitewashed three-story Depot Building still stands, surrounded by acres of roughly mown grass. The crumbling banks of the Hayes River edge a little closer with each passing year.

As I walked around York Factory, I shouted out loud hellos, hoping to find a park ranger or anyone at all to chat with. Even though the doors of a maintenance toolshed stood wide open, there seemed to be nobody home.

A boardwalk led toward the old graveyard. Weathered wooden fences and teetering crosses still surrounded a few of the graves, but the surrounding forest was slowly reclaiming the site. Out of the wind, I was beset by clouds of mosquitoes and gnats. As much as I wanted to photograph the quiet grace of these century-old monuments, I found it hard to concentrate with bugs flying up my nose.

By the time I made it back to C-Sick, an enormous dark cloud loomed over the southern horizon. The storm soon blotted out the sky, spitting lightning, and sending down great bursts of rain and lashing wind. Thunder rolled across the water. I might have been bound for the Arctic, but it felt like I was in a floating trailer park and the tornado sirens had begun to wail.

In the wake of the afternoon’s thunderstorm, T-shirt temperatures returned. Hundreds of miles back in Thompson, I had crammed C-Sick’s tiny cooler with ice and frozen meat and produce. I now tossed what remained of my long-thawed and increasingly dubious-smelling bacon and sausage into a jambalaya mix. The pot, filled with rice and garlic, peppers, and spice, was nothing if not pungent. Not long after I sat down to shovel the gluey mess down my gullet, I looked up and there, mid-swallow, I spied the summer’s first polar bear. The bear was slowly making its way across the exposed river flats, sniffing the wind, and clearly on the trail of something tasty.

If I had to guess, I’d say it was the bacon.

With his size, bulk, and thick neck, he looked to be a big male. Telling male from female polar bears remains, for me at least, an inexact art. There is the matter of size, of course. A big adult male, standing upright, can reach ten feet in height, nearly half again as tall as a fully grown female. The weight differences are even more striking. Females range from 350 to 650 pounds, while the heaviest males can roll in at 1,700 pounds, and the record trophy bear topped 2,200 pounds. There are other, more subtle physical differences, as well. Males, if you know how to look, have necks broader than their heads. Female bears’ heads are larger, which is why they are the only bears to wear radio collars. I suppose the old “lift-the-tail-and-have-a-look” method might work, but I’ll leave that to the trained professionals.

Lord, the bear in front of me was filthy, covered in slop after wading across the muddy tidal flats. Abandoning dinner, I hurriedly snatched up some cameras and hopped into the Zodiac, undid the lines, and began to drift downriver on the current. Just as quickly, the bear lost all interest in dinner—his or mine—and slowly paddled across the broad river, then waded out on the far shore. I consoled myself by muttering abuse at his retreating backside. “Didn’t want to take a picture of your ugly polar bear butt anyway . . . ”

Overnight the wind backed north, pinning C-Sick down where I had anchored her near the river mouth. As formidable as my wilderness boat trips in Alaska had felt at the time, they were child’s play compared to this. Here, I had no shelter but this wretched and muddy river. I had shit for charts and I was left to rely on my wife’s often creative interpretations of the incoming weather forecast. Small wonder no one in their right mind came out this way. There was nothing to do but sit in the rain, stare out at the brown water and gray sky, and listen to the wind.

For two long days, I waited for that wind to ease. I napped and read. I ate leftovers unimproved by time. Finally, I imagined a sip of whiskey might help, and then another, and pretty soon I was singing along with every one of the sad country songs I’d thought to bring. Contentedly miserable, I eventually curled up on my bunk and drifted off upon bourbon clouds.