Читать книгу Cokcraco - Paul Williams - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

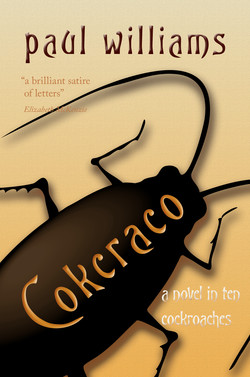

1. Blaberus craniifer

ОглавлениеDeath-head cockroach

The death-head cockroach or Blaberus craniifer is marked with a dark spot on its thorax, which, with a stretch of the imagination, looks like a skull. It will eat anything, even faeces, to satisfy its hunger. It has wings, but is incapable of flight, and chooses rather to confront its enemies by emitting a repulsive odour. It is most commonly found in so-called Third World countries, and because of its markings is often the victim of negative projections.

You’re driving down a red dirt road in the middle of South Africa, having turned off at the intersection of nowhere and nowhere. You’re lost. You’re late for a meeting. The air-con in the rental car doesn’t work, and you’re wearing a European suit. You should stop and ask for directions, but you’re male, genetically programmed never to ask for directions.

Three men stand in the road. One brandishes a panga—a machete. One points the barrel of an AK-47 at your face. The middle one holds up the open palm of his hand and bangs on the bonnet. You stop the car.

1 Umlungu: Zulu (n). Derogatory. White man. Origin: white foam on the beach, i.e. white scum.

‘Where you going, umlungu?’1

‘Open up here, sharp sharp, man.’

Your blood runs cold.

No, no, no. Your blood does not bloody run cold. Only the blood of ectothermic creatures, like frogs, fish, geckos, crocodiles, chameleons, snakes, spiders, centipedes and cockroaches, runs cold. Your blood pumps hot and fast through your body, and your brain sends frantic messages to your fight or flight centres: your heart, your limbs, your brain. Epinephrine increases your heart rate, constricts your blood vessels, dilates air passages, and you’re ready for a fight … or more likely in this case, flight.

Think. Think! You should drive right straight at them, through them; knock them over like bowling pins. But your leg locks into a cramp on the pedal. Two faces press against the passenger window. The leader—the one with the AK-47—stands his ground in front of the car. No false moves, the fearsome eyes say. Try not to stare at the barrel of the ubiquitous AK-47.

Mikhail Kalashnikov, your invention is alive and well.

The one with the panga raps on the glass. Tak. Tak. Tak. ‘Where you going, umlungu?’

Your voice, no matter how hard you try to sound calm, is hoarse and shaky. Don’t show any fear. Pretend all is cool. ‘To … to … to the university.’

‘Heh, heh, heh.’ The young man performs a mini-dance of triumph in front of the car.

Is it too late to pray to the god whose existence you have denied all your life?

This country is the crime capital of the world; South Africa is in Guinness World Records for the highest carjacking figures. A motor vehicle is hijacked every forty to fifty minutes. More than twenty-five motor vehicle drivers become victims of hijackings daily. South Africa also gets the gold medal for murder and rape: a murder every thirty seconds, a rape every fifteen; one in four women have been raped; one in ten tourists has had something bad happen to them. And here you are. Fifteen seconds tick away and the country is waiting for its next victim.

You’re dead.

And they’re waiting.

It’s a rental, you want to say. It’s not mine. Take it. I have no cash. No cash. No gold. But your tongue is thick and dry. Your skin—your white umlungu skin—is clammy.

‘Can we have a lift?’

You must look even whiter now. ‘What?’

‘A ride. We need a ride to the university. Can you give us a ride?’

They’re playing with you. Even now you can drive off, before they get in. A choice: drive and get shot in the back, or give them a lift, so they can slit you from mouth to genitals, discard your lifeless body in the green and red Zululand backdrop. You know. You’ve read the stories.

South Africa has a very high level of crime, including rape and murder. Thieves operate at international airports and bus and railway stations. Keep your belongings with you at all times. Due to theft of checked baggage at airports, you should vacuum-wrap all items where local regulations permit. You should keep all valuables in carry-on hand luggage. There have been incidents involving foreigners being followed from King Shaka International Airport to their destinations by car and then robbed, often at gunpoint. You should exercise particular caution in and around the airport and extra vigilance when driving away. Some taxis and car rental companies are fraudsters …

Crowded-Planet (2013): p. 120

Go on: rev the car, knock them down like skittles, swerve. The reckless hero escapes, tyres squealing as gunshots crack the back windscreen.

But no.

‘No worries.’

They pile in. Two in the back, one in the front. AK man clatters the gun against the door as he wrestles with it. Panga man slides comfortably into the back. The third man has a scar that slices his face into two lopsided halves.

‘Drive, drive.’ AK man indicates the side road to the left where the green sign points into the furrowing valley. University of eSikamanga, 3 kilometres.

A nightmare. A bloody nightmare. What kind of a welcome is this to South Africa? You’re sick to the gut. You want to throw up. But then, what did you expect? That you could drive through South Africa and not be hijacked?

The leader places his feet on the dashboard and props his AK-47 against the door.

You’re careful not to turn your head, but out of the corner of your eye, you take note of the curved banana magazine, the wooden butt drenched in sweat, the notches—notches!—on the matt black stock. The weapon looks plasticky, homemade, as if he’s assembled it from parts of other weapons.

‘Where do I go?’

‘Through here.’

‘Bundu bashing,’ adds the man from the back seat.

So they do mean to arrow you into the cane fields, back you up against a low anthill and murder you. All for this tinny Golf GTI rental. You can hear the shots already, muffled by the six-foot-high sugar cane.

‘Drive—left … left … now straight, straight.’

You drive as straight as you can on the snaking roads.

‘You a professor or something?’

‘Don’t distract the driver, Caliban.’

Caliban? You steal a glance at the man in the rear-view mirror. Remember to identify the carjackers for the police. Caliban. Scarface. Panga man. AK man. Three, four notches.

‘That’s Kaliban with a K. KU- KU-KU-Kaliban, Professor.’

‘Drive, drive.’

You drive.

You count two kilometres of bumpy roads which have been gouged out of the red mountains, and you have to zigzag around goats and stones and ochre earth spills. A mini-bus plastered with ‘I love eSikamanga’ stickers shoots past, missing the car by inches. You should flash your lights to signal for help. Pull up on the brights. Three times. Morse code. Do they even know Morse code here? A weak stream of water wees onto the windscreen and the wiper blade judders across, smearing red dust—now red mud—across your line of vision. Now you can’t see at all. Slowly the wiper does its job.

‘Straight!’

Yeah, right. An AK bullet straight to the head.

‘By the way we’re the New Strugglers. This is Joel, Caesar …’

‘Kaliban!’

‘Sorry … Kaliban. And I’m Eric Phala.’

Their gang, their group, their little carjacking syndicate: The New Strugglers. What a name for a gang! And what caricatures. They are cartoon characters, confirmation of the worst stereotypes from South Africa: the black thug with panga, the AK-wielding carjacker, the silent brooding youth with a scar splitting his face in two.

‘The New Strugglers for a new South Africa.’ The man gives a guttural laugh. ‘Viva the new struggle!’

They smell of heavy deodorant and hair oil as if they are going to a party.

Some party.

A cow saunters across the road. You brake, looking for an opportunity to do something rash. But you can think of nothing. Red rivulets of paths criss-cross the countryside. Another cow prodded from behind by a boy with a stick crosses the road ahead.

‘Just drive—he’ll get out of the way.’

There must be people who live near here, people who can help you. But all you can see is six-foot-high sugarcane.

‘Okay. Okay. Stop here.’

This is it.

You slow the car, and the red dust catches up, clouds the windows and front windscreen. The three men bang open the doors and climb out, the AK-47 again clattering against the door handle, the panga against the window. You’re spitting dust, but have to ask. ‘Where are we?’

The AK is pointed at your head. The sun is screaming (or are those cicadas?). The man with the scar grins. ‘This is it, umlungu.’

It is at this point that your life is supposed to flash before your eyes. You know you’re going to die, so you quickly review your life, and realise—too late—how precious every moment up to this point has been. If only you hadn’t stopped at this intersection; if only you hadn’t come to South Africa at all, if only she hadn’t left you … if only you could rewind your life, just a little, just a few minutes. Why the hell did you drive down this back road?

This is the point when you feel an AK bullet in your brain, your soul rises up from your body, and stares forlornly from the branches of a tree at your dead white male protestant heterosexual corpse.

This is the point where you should wake up, sweating, heart racing, thinking—whew—it was only a dream. And what a nightmare.

The man swings the AK to point through the green jungle to a red flash of roof, a metal aerial glinting in the sun. ‘Through there.’

Caliban—Kaliban—grins into the front window and bangs on the roof. ‘Thanks. Thanks, man, for the ride. Nice wheels. Nice wheels.’

You steel yourself for the climax, the confrontation, but when you open your eyes, they are plunging into the green foliage, following a thin red path. Then they are gone.

The world stops for a second; even the cicadas stop screaming.

As soon as you can stop your leg from shaking, you drive on, wary of a trick, a trap, ready for the clatter of bullets in your skull.

But no.

Ahead, as you round the corner, you see red and white boom gates, a guard house, three men in green uniforms lolling in the shade. But it is no mirage. You take three deep breaths, pry your sticky hands off the steering wheel, slow your heart. Look down the path that has swallowed them up, and up again at the banner.

‘The University of eSikamanga’, announces a sign arching over the road in English and Afrikaans, the language of the former oppressor. Universiteit van eSikamanga.

From the point of view of da cockroach, all languages are da languages of the Oppressor.

— Sizwe Bantu, Seven Invisible Selves, 2008

You drive under the arch, and your car putters to the booms. Your heart is still pounding way too loud and fast but your mind is numb, as if you have indeed been murdered and are on the other side, your ghostly self still insisting you have a body, and you are driving an imaginary car to a spirit university entrance.

A security guard leaps out into the road. He looks real enough. ‘Whoa, whoa!’ Another walks in front of the booms, holding a clipboard, his peaked cap low in the glaring sun. He bangs the bonnet with an all-too-real fist. ‘Stop! Stop, wena.’

You stop.

You eye the man’s pistol tucked away in his pocket.

You speak. The words, surprisingly, come out as words that you can, and he can, hear. ‘Th … th … those men … ?’

The guard pokes his cap into the front window. ‘They think I don’t see … ? I saw them! I saw them!’

2 Skabenga: South African (n). Slang. Rascal, scallywag.

3 Tsotsi: South African (n). Slang. Thug, dodgy character (from Nguni tsotsa: flashy dresser).

Guard number two holds out his clipboard. ‘We try not to encourage giving them lifts, Professor. Especially those ones. Skabengas.2 Tsotsis.3’

‘You … know them?’

Guard number one shakes his head, meaning yes. Guard number two clicks his tongue. ‘Troublemakers.’

‘One had an AK …’

You are not sure they understand you. A BLOODY AK, you want to shout. But perhaps that is normal around here. Perhaps everyone carries weapons in South Africa. The guards certainly do.

He hands you the clipboard. ‘Welcome to the University of eSikamanga.’