Читать книгу Cokcraco - Paul Williams - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

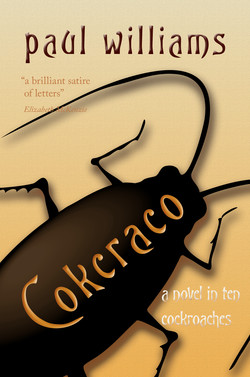

3. Periplaneta americana

ОглавлениеAmerican cockroach

American cockroaches (Periplaneta americana) are the largest cockroaches found near human habitation and can fly, although they do not get their wings until adulthood. Prolific breeders, they can hatch up to 150 offspring a year. Interestingly, the American cockroach which has spread all over the world is thought to have originated in Africa and was possibly brought across in slave ships in the 1600s.

You wake at five thirty a.m. to a rustling of leaves, cawing and scratching. Outside your window, a squadron of birds with oversize beaks and scruffy black and white feathers are feasting on the paw-paws. Are you seeing right? They look dinosauric, rhinosauric, prehistoric. Shoo. Shoo. You bang the window sill. Bugger off. Only then do they dip and dive in a curious arc of flight above the house. Makaya! Makaya! Makaya! they call.

The sun prises open the horizon and blood oozes through the cracks.

You stumble through the garden—barefoot—to salvage a paw-paw and twist it off its stalk. This was supposed to be my breakfast, you thieving bastards. You slice it open with a pen knife, scoop the black pips out and grind them into the red earth. Then you sit on the back step to eat and watch the sun ripen through the trees. The sea pounds at the coastline.

In the bathroom, a scorpion claims your green toilet bag, and its tail arches as you try to reach for your toothbrush. It is small—three centimetres—but these buggers are deadly. You clamp a shoe box over it and carry it to the edge of the lawn where you shake it off into the rubbish heap.

You are used to creatures that kill with one bite, sting, suck, or zap. Your five-year-old niece nearly died of a paralysis tick bite in North Queensland. The Australian bush is dripping with brown snakes, black snakes, tiger snakes and taipans (to name a few of the more deadly species). But here in Africa you don’t know the bad guys from the good guys yet.

And then there is the gecko that clings to the ceiling of the bedroom all night catching mosquitoes and making kissing noises every time you try to drift off to sleep. In the morning it occupies the bathroom while you shower. It follows your every movement, watches you take a crap, and cocks its head at the clanking of the toilet roll against the wall.

Lizards drop their tails as decoys to allow them to get away from predators. All lizards have detachable tails. Which is why humans need tales too, to trail along behind them, to give them balance. And what are tales for? The analogy swishes its way through the jungle. Detachable tails are for self-preservation, to distract predators and entertain unwelcome visitors. Leave them wagging like tongues so that the teller of the tale can escape. But beware the tales that do not detach. Scorpion tails have a sting at the end. Cockroaches, on the other feeler, have no tales to tell, so to speak.

Sizwe Bantu, ‘The Tale of the African Lizard’ from Ubuntu! Vol. IX, pp. 23-24.

There are the insects: long-legged spiky hexapoda, shiny black monster centipedes, a freeway of ants, each the size of your thumb, beetles sporting rhino horns. Spiders—again you are used to huntsmen and funnelwebs—but here monsters lurk in every corner, black widows under the kitchen counter and the chairs, and aliens with swollen abdomens, their backs crawling with a million baby spiders—the stuff nightmares are made of.1

1 Superstitions have given rise to many myths about cockroaches; for example, the myth of the dreaded African kissing bugs. One bite will make you itch forever, and not an ordinary itch, but a sexual itch that drives you mad with desire, and leaves you unable to ever satisfy your lust.

You pour your cereal into a bowl of preserved milk and out scramble five live cockroaches. They swim valiantly in the milk to reach the sides.

‘Bloody hell.’ You scoop them out, contemplate eating the cereal, but decide against it and pour the mixture into the flowerbed outside. The packet is crawling with cockroaches, so you dump that too.

Cockroaches have made themselves at home in all your packets, even chewing the cardboard that holds the cereal. Three large Oriental/ African cockroaches scurry away as you open the pantry door. You find the nearest weapon—a tea towel this time—and whack them to death. One escapes, crippled, a serrated leg left behind in the sugar bowl, but you smash it with your shoe as it tries to squeeze into a crack in the floorboards.

Your love of the cockroach is only theoretical, symbolic, literary. You wonder about Bantu’s obsession with these pests: is his fascination with the Periplaneta, Blaberus and Blatella species also only theoretical, or does he keep them as pets, revere them as tiny gods of the oppressed? Does he study their behaviour to get inspiration for his material?

It is time for work. In spite of the cold shower, you are already sweating. You have to dunk your head under the tap before donning the suit.

Surely this is madness? How soon will you be able to shed this skin? But the suit, you have to remind yourself, is the uniform of the supercilious sneerers. And you are now one of them. Funny that. You go to university, ranting and radicalising, not realising you are one of the elite, and then you finally capitulate and take your place as oppressor of yourself.

But if you look smart, the rental car looks a right mess. It is wet with dew. Mud has splashed up the doors and bumpers and caked dry; road dirt has sprayed up onto the windscreen and roof; and the tyres look a little depressed, if not entirely miserable. The exhaust makes a farting noise if you rev it too high.

You arrive on campus at seven thirty. No armed gangs of thugs or ambushes intercept you this time, but just past the Mazisi Kunene turnpike, an impi of Zulu warriors wheels onto the verge of the freeway ahead of you and marches in squadrons of four abreast along the verge. They are singing some war song, their bare chests glistening in the sun, spears whacking their shields in time to the beat. Cowhide shields, knobkerries, spears, the lot. Is there a war on you don’t know about? Or a remake of the movie Shaka Zulu you have stumbled into? But other cars whiz by unperturbed, so you do the same.

Even this early in the morning, the university is rivuleted with students in jeans, joggers and sandals, t-shirts with corporate logos, and backpacks. You squeeze past giggling triplets of women, heavy phalanxes of men; you listen to loud conversations held on mobile phones by students staring through you at electronic friends. Students slouch in the shade, or drape themselves onto benches, or brush past you, engaged in fervent dialogues about important matters. You understand nothing of the clicking, musical language. What good was that iZulu language course you took on the plane on the way over here?

Sawubona! Wena unjani? Ngi khona.

The Honours classroom is an octagonal over-air-conditioned room with no windows. Ten pairs of eyes follow you across the room and watch you dump Modern South African Literature on the podium. Seven women, three men: the student elite of the university.

None of these students has textbooks. You have been warned.

The women sit in the first three rows, cushioned in groups of solidarity. The men, as men do, sit in the dark of the back row, arms folded. One places his runners on the desk in front of him. Another wears his cap backwards on his head. Another in gang-baggy pants holds a phone to his ear.

Your attention is focused on the female student in the front row. Her thick blonde dreadlocks hang halfway down her back, tangled with beads and shells. She wears a black bowler hat at an angle, and her pale green eyes are bright in contrast to her dark skin. She’s like a creature from the deep who’s been washed and tumbled into existence by a briny sea. The way she stares at you, and the way others look at her, tell you that she is used to being the centre of male admiration and attention. Here is another person who speaks to the world with her body and not her words.

Do you need to casually mention the AK-47 propped up against the cupboard in the corner? And … is this a panga you see before you, lying on the front desk, stained with dried blood?

As your eyes adjust, you see them—the three hijackers in the back row. Kaliban. The AK man slouched in the front row, his feet up on the desk; next to him, the man with the scar.

Should you call security?

Should you make a leap for the AK?

Or should you simply clutch the podium tightly and swallow hard, staring in turn at the panga then the AK then the students, grinning like an idiot?

‘You remember us?’

‘Joel.’

‘Kaliban—with a K.’

‘His real name however is Caesar Langa.’

The nightmare resurrected. Panga man, Scarface and AK man. You swallow.

‘The New Strugglers.’

You open the folder and run your finger down the student list. Sure enough, here they are: Eric Phala (pronounced ‘pala’); Caesar Langa; ‘And you must be …’

‘Joel Matinde.’

‘You … you’re students? Honours students? And is this … (pointing to the AK-47) … allowed in a lecture hall?’

They grin like crocodiles.

‘Forgive me, I’m not from South Africa—perhaps this is common practice here …’ Like the impi of Zulu warriors, burnt-out offices, the Frankenstein stitches on Zimmerlie’s head—all perfectly normal.

‘It’s for the play, sir.’

‘The play?’

‘The Tempest.’

The AK, gunmetal heavy symbol for liberation and oppression, shimmers before your eyes. You stare. The AK is crude and badly made: salvaged from parts of guns to be sure, but non-functioning—the barrel a piece of pipe, the butt (with notches) from a plastic toy gun you could buy in any supermarket. The panga—real enough—is also a prop, blunted, daubed with red paint.

‘Is this what you were carrying with you yesterday?’

‘We’re doing The Tempest for our group Honours Project,’ explains Eric Phala.

‘Kaliban, you see, takes up arms against Prospero, liberates the island …’

‘The Kapitalist Kolonisers—both with a K—are banished …’

‘Driven into the sea.’

‘I’m Ariel,’ says Scarface. ‘He is under house arrest by Prospero and has to do his bidding until he negotiates a settlement.’

‘Trinkulo with a K.’

‘Wait, wait. You’re putting on The Tempest. With an … AK-47?’

‘A modern version,’ says Eric Phala. ‘Where the oppressed have weapons to fight back.’

Joel Matinde: ‘We rewrote the entire play ourselves. Workshopped it.’

Kaliban: ‘The New Strugglers—that’s the name of our play group.’

Eric Phala: ‘The New Struggle for a New South Africa.’

Joel Matinde: ‘The New Struggle for the Post-Apartheid, Post-New South Africa.’

Kaliban gestures to the ceiling: ‘You taught me language, and my profit on it is, I know how to curse. The red plague rid you for learning me your language!’

You cannot keep your eyes off the AK, wondering now how you could possibly have mistaken it for the real thing. It is a crude caricature of an AK-47.

You feel, not for the first time in your life, very foreign. Your perceptions are slow as mud.

The woman in the front row hasn’t said a word yet. She folds her arms and watches you with ironic superiority.

‘And you are?’

She does not answer. The men at the back speak for her. ‘She’s Miranda! Miranda!’

‘Prospero the Kapitalist’s beautiful daughter,’ says Kaliban.

‘But in our version,’ says Eric, ‘she marries Kaliban, not the prince!’

‘And what’s your name, Miranda?’

Finally, she deigns to speak. ‘Tracey Khumalo.’

‘Is that Khumalo with a K?’

Your eyes meet. She tosses her braided hair over her shoulder and the beads and bells clatter and jingle. An echo of a past ache inserts itself in the present, cuts and pastes itself onto her, squeezes your heart for a moment, and then is gone.

Beauty and good looks, which are merely accidents of biology, should not influence how you treat a student, or any person for that matter. And why should such an accident of beauty (and beauty is always relative, constructed) elevate a person’s status in the eyes of others? So you refuse to pay homage. Or try not to anyway. But her green eyes follow your every move, like a cat about to pounce on its prey.

‘What have you guys got against the letter C?’

She speaks to you as if you are an idiot. ‘It’s not African.’2

2 The letter ‘c’ in IsiZulu is pronounced with a click, not as ‘see’ or ‘kay’ as in most European languages, hence the comment that it is not ‘African’. This is nothing unusual. Most English speakers don’t like the letter ‘t’. Cockneys and Londoners say ‘w’ instead of ‘th’, and when they can possibly help it, leave out the ‘t’ altogether: ‘writing a letter’ becomes ‘wri’in a le’a’. Americans and Australians, however, prefer a ‘d’ to a ‘t’: ‘wriding a ledder’. But Tracey is probably referring here to the word ‘Afrika’, the name adopted by black consciousness movements during Apartheid South Africa which strove for a New Azania. The ‘a’ and ‘k’ were of course a subconscious draw card. Ironically the word is also spelled ‘Afrika’ in Afrikaans, the ‘language of the oppressor’. The word ‘Africa’ itself is, of course, not African, as Sizwe Bantu tells us in his ‘Notes on Azania’ (see p. 165, Seven Invisible Selves.) Africa is the Latin name for this continent, kindly bestowed on it by Roman imperialists. And if we want to play the reductio ad absurdum game, none of the letters ‘a-f-r-i-c-a’, or even ‘k’, are African either.

You could say something here. But you don’t. ‘So, who’s playing Prospero in your play?’

‘We still don’t have anyone to play Prospero. We need a white man, and no white man has volunteered.’

You have sufficiently regained your composure. ‘Why am I not surprised?’

The men at the back laugh.

You are aware of the baggage you carry, that they carry: that this superficial friendliness is not real, that underneath this banter is a century of resentment against white men, of which you are one. You have to tread carefully. But your instinct is to say to hell with treading carefully. Culture is not god. Culture is a mould growing and feeding on people, a deceptive green furry substance. You believe that underneath all racial, gendered, cultural, religious and political impositions, there is a fundamental sameness, common ground and this is what you need to tap into here. Vive la similitude!

For example, they have an ironic humour you can relate to. Their attitude to the world is wry and sceptical, a familiar stance. The distance with which they measure themselves from others is a trait you might say you had yourself. They exude a dark, restless energy. This is a language you have in common.

You gesture to the six women who sit stony-faced in the middle rows. ‘What parts are you ladies playing?’

Joel answers for them. ‘They’re the chorus. They comment on the play in a unified voice.’

‘The main parts of the play are traditionally taken by men,’ offers Scarface.

‘And what do the women think of that?’

‘They agree with us,’ says Joel.

Tracey twists her body to face the back row and says something in Zulu which is undoubtedly a swear word.

Scarface rises in his chair, but Kaliban pulls him down again.

You cannot keep your eyes off the scar that runs from the corner of his left eye to the right corner of his mouth, his nose split in two by what could only be an axe stroke. You politely try to ignore it, but it is obvious you are uncomfortable. You cannot help wondering: Zimmerlie’s scar, the mutilated kitten, and now this.

They notice, of course. ‘Hey, ushomi,’ calls Kaliban, ‘don’t worry about him. He was in the struggle, and they chopped him.’

‘The struggle?’

‘The Old Struggle,’ explains Eric. ‘Against Apartheid. In detention, they chopped him.’

They are having you on, you are sure. He is far too young to have been involved in any struggle. Apartheid ended in 1994 and this man can be no older than nineteen or twenty. But who are you to argue? He carries his scar like a veteran’s medal.

‘Tell us about yourself, sir,’ says Caesar Langa. ‘What are you doing in eSikamanga? How did you end up here?’

You loosen your tie. ‘Well, let’s say I didn’t really “end up” here, since this is hardly the end … I applied for the job on the internet.’

When Tracey speaks, her voice is husky. ‘Where you from, Dr Turner?’

A year ago you would have been attracted to her, smitten even. You watch her with dissociated fascination. You’ve been here before, and you know it’s treacherous territory, so you just watch yourself watching her. Thank god for scar tissue.

‘From Australia. Melbourne, Victoria. My Ph.D. is in African Literature … well, Postcolonial, Post-Apartheid, Post-Struggle Literature. I studied the great writer Sizwe Bantu … and focused on the African Subject in the novels of Sizwe Bantu.’

‘Who’s Sizwe Bantu?’

‘You’re kidding me? Sizwe Bantu, you know, the great South African writer!’

‘Sizwe Bantu?’ She closes her eyes and taps the pencil on her teeth as if to evoke the vast catalogue of African writers she knows in her mind. ‘Never heard of him.’

Now she is pulling your leg. Surely. ‘That’s funny. He’s in the book that is set for you this semester …’

She shrugs her left shoulder and the shells, bells and bric-a-brac in her hair jangle and tinkle. ‘We didn’t use that book.’

‘Which one did you use, then?’

She taps her forehead with her pencil. ‘This one.’

You cannot help staring at the green eyes. ‘That’s not a textbook.’

Her smile is bewitching, seductive. But you shake your head.

Eric Phala indicates the books piled up on the end desk—ten copies of Modern African Stories, neatly spider-webbed and covered with what looks like a semester of dust. ‘We must create our own African traditions, not passively receive those which have been imposed upon us.’ It sounds as if he is quoting somebody.

‘You didn’t use any books at all in this class?’

Tracey pulls out a pink A5 book from her bag. You read CREATIVE WRITING JOURNAL printed in neat handwriting on the front cover. ‘We’re not naïve consumers of multinational corporate products. We wrote our own textbook. Wrote our own play.’ Her words are spiky, her body language defensive.

Eric Phala concurs: ‘Creative Writing gives power back to the people. Creative Writing breaks down the elitist idea of a literary canon.’

‘And what’s in there?’

‘Our own authentic experience of the world. The real text. We wrote about …’

You reach out to take her journal, which she is holding up in the air as if to pass to you. A hiss of disapproval snakes across the back row and she hastily plunges it back into her backpack. ‘It’s nothing really,’ she says, ‘just a way to make us write honestly.’ A mobile phone prods her back and she arches in annoyance.

‘I see.’

You stare at her a little too long. ‘What?’ she says.

‘Nothing.’

You remind me of someone I know, you want to say. Someone ten thousand kilometres away whose name begins with M. Someone I am trying to shut out of my heart. Someone familiar, someone unstable.

You sense that her bravado is a mask for her vulnerability. But you are also aware of how you project your own psychological defects onto others.

Time is ticking by on the large clock on the wall. You only have a few minutes until the end of the lecture. You distribute the ten copies of Modern African Stories to the ten students, and take your place at the podium.

They fidget and whisper.

‘What?’

‘Nothing, nothing,’ says Eric.

‘All right then. Will you please open your texts at page 343 and read the poem you find there: Bantu’s ‘The Bloody Horse’. Please read for me, Mr Phala, the poem you find before you.’

Mr Phala opens the book, and then slams it shut again. Smiles.

‘What’s the matter?’

‘I don’t have it.’

‘What?’

‘That page is missing in my book.’

‘Okay, Caesar, you read it.’

‘That page is missing in my book too.’ He holds it up.

You walk across and examine the book, check Eric Phala’s too, and find the same careful tearing along the centre spine of the book. ‘Did you tear this page out, Mr Phala?’

He frowns, as if trying to remember.

‘Does anyone have that page?’

All open their books to the same empty space. No, of course not. ‘Okay, what happened?’

The class ripples with grins and nudges.