Читать книгу Cokcraco - Paul Williams - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

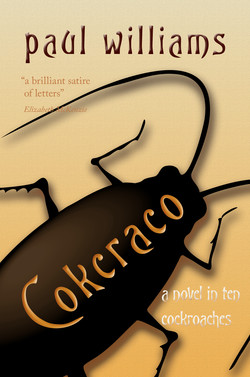

2. Supella longipalpa

ОглавлениеBrown-banded cockroach

Often found in bedrooms and living rooms, brown-banded cockroaches (Supella longipalpa) are hardy creatures that shun the light, lay their eggs under furniture, and scavenge off humans. These creatures are the most common cockroaches found around the world. A popular misconception is that cockroaches are dirty creatures that carry disease: nothing could be further from the truth. Cockroaches are the garbage collectors of society and if allowed to go about their business, will keep a house clean and free of food waste. Toxic when eaten raw, they nevertheless are a popular culinary delicacy in certain parts of the world.

1 eSikamanga is off the beaten track, a beautiful town with kilometres of unspoiled beaches, and has the air of not having being ‘discovered’ yet, as well as a laid-back lifestyle enjoyed by residents distrustful of change in any form. But, surprisingly, Zululand’s most idyllic coastal hideaway is off the grid. Residents voted to exclude it from tourist listings, block all advertising on the internet and to discourage large-scale tourist activities. There are no hotels or bed and breakfasts, and residents do not encourage visitors.

The road to eSikamanga1 is lined kilometre after kilometre with good intentions—Zulu goods for sale: beads, carvings, grass mats, hats, bangles. Vendors crowd every dusty intersection. You would stop, but of course you don’t. It’s also lined with carjackers.

As the car crests the hill, your heart lifts to see the sparkling Indian Ocean, the sweep of enormous sand dunes, the gold beaches.

You have dreamed of this moment.

Careful not to slow down at intersections or give anyone rides, doors locked, windows down, you cruise along vacant streets and parks until you reach the eSikamanga Mall, a stretch of low buildings with large verandas, boasting a SPAR Supermarket, Chemist, Zulu Souvenirs and Curio Shop, Estate Agent, and Mrs K’s Take-Aways. You are also pleased to see a police station in the prominent centre of the square, a hunched building bristling with aerials, completely enmeshed in barbed wire fencing. Amazing how theoretical one’s anarchism can be.

You pull back a strongly sprung front door and plunge into the ice-cold air of the dimly lit estate agency. A woman with red bifocals pushes back tired grey-blonde hair from her eyes.

‘And what can I do for you?’ Her eyes are narrow, her lips pursed.

‘Timothy Turner, from the University of eSikamanga.’

‘Oh! Professor Zimmerlie called me with the good news. Said to expect you. Thank god. They’ve found someone to replace that dreadful man. I hope for your sake you never have to meet him.’

‘I’ll do my best.’

‘Mrs Steyn.’ She thrusts out a hand. ‘So, Dr Turner—it’s Dr is it, or Professor?—I have exactly what you’re looking for.’ She taps a long red fingernail on the glass counter top. Under the glass is a map of eSikamanga, a grid of streets sandwiched between two snaking rivers and a large blue estuary. ‘We have a nice town house for you here—going for four thousand a month: three bedroom, two bathroom, one ensuite … very clean, modern. … Electronic security. … Neighbourhood Watch.’

‘I … I was looking for something more … modest. I … don’t know how long I’ll be staying, you see.’

‘Oh, don’t worry about that.’ She crouches over the counter in a confidential invasion of personal space.

Some people occupy more space than others, see their bodies as missiles or blockades, and colonise your space, extend themselves in an aura that radiates far beyond their body space. They squash you into a little corner and thrust their physicality at you to make you acquiesce. Mrs Steyn, intentionally or not, thrusts out her breasts at you in some territorial display of aggression. You could be wrong—this would be a ghastly error of cultural judgement—but you feel she is challenging you to a battle with the world, one she has to win at all costs.

‘Those are only rumours about his reinstatement. You’ll be here a long time … a year’s lease to start? Professor Zimmerlie told me you have a twelve-month contract.’

It is all to do with bodies. We pretend we are rational beings, consciousnesses, and drag these bodies apologetically (as a white man, you speak for yourself here) but there is another language we speak all the time, the language of the body. And women, you are told, have sex organs just about everywhere. Mrs Steyn’s relation to you is … in a broad sense … physical, sexual, through the body, not through the mind.

You loosen your tie, that ghastly British invention designed to choke and pinch your neck. In fact, you now realise, the suit is a way of denying the body altogether, bracketing it off from everyday discourse. ‘I just need a one-bedroom. I don’t mind an older place. Nearer the sea, perhaps? And a shorter lease to start.’

‘Do you have family here?’

‘No …’

‘And you’re from Australia?’

‘This is a smaller town than I thought.’

‘Everyone knows everyone’s business here, Dr Turner. And that’s a good thing: we look after each other. Australia, hey? Why come here?’

‘Call me Tim.’

‘My sister moved to Perth a few years back. Refuses to come back here to visit. Lovely place. You know Perth?’

‘I’m from the other side, actually. Never been to Western Australia.’

‘Hmm.’

You browse the photos of houses for sale on the adjacent wall. ‘Haven’t you got anything cheaper … smaller?’

‘Most single professors live in the block of flats called Strandloper. They pay from six to ten thousand Rand a month. They’re large apartments, safe, secure …’

‘This for instance.’ Your finger hovers over a picture of a thatched cottage standing on its own in the midst of a wild garden. In the background, a misty blue ocean fogs the sky.

‘Oh, you wouldn’t like that. It’s …’

Acid rises in your throat.

‘ … too small and run down. Hasn’t been let for years. Running water a little temperamental; gas heating; you have to buy the canisters from the general store. Garden uncared for. And for security reasons, most of us live in gated communities.’

‘So, just how bad is the crime here?’

‘Oh, nowhere’s safe these days, but I did mention our Neighbourhood Watch at Strandloper?’

You tap the glass. ‘How much?’

‘The cottage? I could let you have it for … six thousand at a squeeze. But you’d be sorry. You’ll regret not paying the little extra to have comfort and security.’

‘Could I have a look?’

She looks at you over her bifocals as if she has only just noticed you are in the room. ‘Fine.’ She bangs open a drawer, scrapes her chair, snatches a key chain off the hook on the wall behind her, and then motions you to follow her outside to a white Mercedes, where she fusses with jangling keys, unlocks the car, disarms some complicated alarm system and lets you slide into the white leather front seat. Then you are swishing down the roads towards the residential area on the west side of town.

The Post-Apocalyptic Guide to Parochial South African Towns Buried in the Past

eSikamanga is a squat, hunchback town which, because of some curious disposition of the land, turns its back on the sea. The high sand dunes and the swampy area between the Manga and the Mswaswe rivers squeeze the town into an unhealthy, uncongenial spot in the mangrove swamps. The town is a vestige from the Apartheid era, very white, a neighbourhood-watch-starts-here type of town.

Crowded-Planet (2013): pp. 122-123

She drives past glass-fronted houses with pools and fountains on large multi-acre grounds, private jetties jutting out into the lagoon through the dense green scrub. In her last valiant attempt, she cruises (by chance, she claims) past Strandloper, an offensive walled-off row of town houses, with a blinding white reflection from the sun on the high walls. Three strands of electric fence top the wall and a sign warns intruders (in three languages) of the danger of electrocution if they even dare to think of breaking in. She nods at the walls; you shake your head; she drives her Mercedes impetuously down a narrow gully of a street towards the sea. She turns down into a dirt road to the left, named Seaview Street, the sign almost completely screened by palm trees. The lane is strewn with dry palm fronds and rotting leaves; a deep ditch of dried red mud runs down the middle of what must have once been a driveway. She takes delight in roaring her car over the bumps and roots, as if to say: see—this is not what you would want to rent.

The property is surrounded—as all others are, nothing unusual here, apparently—by a high electric barbed-wire fence. She stops at the gates, looks around and then unlocks it.

‘Most attacks occur at the entrances of the security gates,’ she says.

‘Most people seem to live pretty much like prisoners in their own houses,’ you reply.

Parrot-blue eyelids, laden with heavy black mascara, blink at you. ‘In Australia you don’t have high security walls around your houses?’

It is of course not a question: it is an answer to a question. She sighs. ‘Like in the old days. I bet you don’t even have a key to your house.’

But your fears of being in a high security prison are soon allayed. Once inside the grounds, the perimeter fence is swallowed up by greenery. The drive opens out into a wide expanse of green lawn which fronts a bad copy of the photo in the estate agency. The cottage, it seems, is sinking in the mud of a recent flood. The walls are red up to the windows, and the roof is strewn with fallen branches and leaves from the overhanging trees. A line of brown and green mould circles the house at shin level. She parks in front of the veranda door. Two large birds fly off in alarm from a paw-paw tree’s yellow fruit. She drums her fingernails on the steering wheel. Surely her client will now acquiesce, shudder and return to Strandloper with all due haste? Instead, you step out of the car and onto the red polished veranda.

‘Wait!’

You turn to see a blur of grey fur dash past your feet, followed by a long tail. Then more blurs, more tails. They leap from the veranda wall onto the trees and swing through the branches. One bounces on and off the bonnet of the car, bounds into a tree and disappears. You watch the passage of a troop—ten, twelve—through the treetops.

One last one leaps on the roof of the car and clutches the aerial. You stare at its human face.

‘Cute.’

‘Vervet monkeys are not cute. Damn pests. Shoo! Shoo!’ She claps her hands and waves her arms at the monkey, but instead of bolting, it bares its yellow teeth and red gums. Then it swings up into the trees, and the branches shimmer as it catches up with its troop.

‘You can’t leave anything outside. They’ll steal whatever they can lay their thieving little paws on. And never leave windows open.’

You turn to the cottage.

Sure, it is mean, its windows covered with gauze netting. Cracks spider down the walls; the front door is overgrown with a fierce creeper that is reluctant to yield as Mrs Steyn pushes through into the dark entrance hall.

‘Electricity needs to be turned on. But Dr Turner … ?’

‘Timothy.’

‘There’s no phone line or TV connection. No internet connection. You’ll have to ask the telephone company to …’

‘I don’t need a phone. Or TV. Or the internet. I came here to get away from all that.’

‘Oh, really?’ She yanks up a blind at the far end of the room, and grey light streams through a high window.

‘I can’t believe the mess.’ She bends to overturn a box and a large cockroach scurries into a crack in the skirting board.

She knows you won’t like it. But you do like it. Not because you are perverse, and want to break her will—well, perhaps there is a slight element of that too—but it has something. It feels good. Exactly the kind of place you had in mind when you imagined this trip. And—most importantly—you can hear the crash of the sea. You force open a door onto a back veranda and breathe in the briny air.

Amazing, you think, how different a self you can be with different people. The stutter, the grey invisibility has gone, and you are a solid presence before Mrs Steyn. Something about her you like, but there is also something about her that nauseates you. Most of all, you are solid and real. You like yourself in this role.

With a flick of her wrist, Mrs Steyn indicates the back wall of a three-storey house that obscures any view of the ocean. ‘I wasn’t planning to rent this out, and as you can see I haven’t rented it out for a while.’ She catches you running your hands down a yellow surfboard propped up in the corner. It is dented, chewed off at the end, and granuled brown from all the wax. ‘Oh, I’ll have that removed …’

‘No.’ You hold it up to get its feel. ‘I might like to try it out, if that’s okay.’

Mrs Steyn presses her lips tightly together. ‘The sea around here is dangerous, Dr Turner. No one swims here. There are sharks … there have been shark attacks.’

‘Leave it here anyway. I like it. Ambience …’

She marches into the kitchen and peels a ‘Surf Wax’ sticker off the window with angry nails while you tour the rest of the cottage, stumbling over boxes, pulling up blinds.

‘I’ll take it for four thousand.’

‘I said six thousand.’

‘Look at the condition of it!’ You tap a broken window pane and the remaining triangle of glass shatters on the veranda outside. Oops. ‘Four thousand.’

‘Call it five and it’s yours.’

‘Month to month lease.’

‘Are all Aussies as hard-nosed as you?’

You smile. ‘Yes, or no, I can’t win that one.’

‘You won’t need a deposit, as your job will stand as surety. Our office doubles as the building society. The university will transfer your salary through us, so you need to open an account on your way back. And give us your mobile phone number too, won’t you?’

‘I don’t have a mobile.’

The silence on the way back to the mall is horrible, as if she is waiting for you to confess that you do have a mobile phone after all, or that you will relent and plead to be taken to Strandloper post-haste. But you hold your ground.

* * *

Dear M,

They say the depth of the pain is measured by how many kilometres away you have to travel to stop feeling it. I am now 9,837 kilometres away from you. They also say that you only will stop feeling pain when you stop writing to the person who causes it. I must stop talking to you in my head. I must stop seeing everything through your eyes. Stop doing everything for your approval.

They say too (who is this they?) that when she stops playing herself as the feature film in your life, you will be cured.

But for now, a flick of your blonde hair, wide eyes, a hand reaching forward, an old song playing in my head.

Yours T

* * *

You stand in the frame of the front door, savouring the moment. It is a moment of triumph, really, your stand of independence, your rebellion against the past, your dream. For haven’t you imagined this moment, free of sticky pain, the joy returning, yourself emerging as a separate being?

The cottage stinks of mould and rotten seaweed. You creak across the wooden floors to the bedroom, where you find a bed covered with a pink blanket and pink pillows, a dresser sagging in the corner, a pink rug, blotched with cockroach droppings. Back in the living room, a pile of depressed suitcases draped with a cloth serves as a table; there is also a dusty sofa, a stiff office chair, and a rickety bookshelf eaten away by termites at the back. In the kitchen stands a silent Frigidaire (which you regret opening). A dripping tap has stained the sink. The small stove works on gas—you flick the canister with a fingernail and hear a hollow ring.

The windows are mostly glass free. Rusty gauze, linted with years of human skin particles, cage each window to protect the house from the monkeys, presumably. Never mind the panga men and AK-wielding thieves. But the security system comes fully equipped with a panic button, and no one, Mrs Steyn reassures you, can get past FREEMAN security.

And there are boxes everywhere, as if the previous tenant was evicted before he had time to move out his stuff. The boxes are sealed, heavily taped, and labelled BOOKS, CLOTHES AND SHIT, SNORKELLING GEAR.

You haul your suitcase from the boot of the car into the house, and change into shorts and t-shirt. You store the suit on the wire hanger in the bedroom cupboard, shove the boxes off to the storeroom, and sweep the sand and cockroach droppings out with a straw broom you find in the kitchen closet.

On the makeshift table, you set up the Sizwe Bantu collection. You arrange the novels, prop up a grainy photograph of the author’s famous quote (Worship yourself: be your own guru) against the books, and place a large varnished rubber cockroach in the centre of the display.

* * *

Blurb from the back cover of The Great South African Novel (first edition, 2006, reprinted 12 times; this edition, 2013):

Sizwe Bantu is considered by many to be the greatest living novelist in the English language.2 Spanning five decades, his ambitious narrative project has been consistent in its focus to explore the “nerve centre of being” and “unveil the masks of our … civilization.”3 He has dissected the sexist, racist and speciesist “myths of our time”4 with intellectual courage and honesty, and has pushed the boundaries of the genres his fictions inhabit. He has won so many awards for his writing that it would be tedious to list them all. He is most renowned for his cockroach stories and his use of experimental second-person narratives and wry irony. He has succeeded in being both a popular and a literary writer, ploughing through that distinction with ease, and taking delight in leaving piles of overturned critics writhing on their backs in his wake. Simultaneously, he has attracted a cult following of believers, fervent admirers who live and breathe Bantu, and carry rubber cockroaches in his honour.

A formidable recluse, Sizwe Bantu has never appeared in public, has never shown up to claim any of his multiple awards, and does not give interviews. No one knows where he lives, and though his novels are invariably set in the urban and rural thickets of KwaZulu-Natal, they have an allegorical, ahistorical air about them, as if he has never lived there.

2 Pantheon (2013), ‘Bantu, a Disembodied No Man’ in New York Times Review.

3 Tom Watt’s comment on the back cover of the 2008 Penguin edition of Seven Invisible Selves: ‘Bantu’s vision goes to the nerve-centre of humanness. His incisive narrative seeks not merely to reflect back to us the horror of our human condition, but to peel off our black and white skins and unveil the masks of our so-called civilisation.’

4 Sizwe Bantu, ‘Sivilization’ in The African Presence, Vol. 2, March/April 2005, pp. 31-34. Bantu, quoting another great South African writer, speaks of two types of literature, one that seeks to reinforce the myths of ‘sivilisation’, and one that dissects these myths.

* * *

You find a box of matches and a pack of six white candles in a kitchen drawer. You strike the match and light a candle, melt its rear end and mash it onto the windowsill. You place the placard on which you have hand-written the author’s poem ‘Imbrase kontradikshun’ on the wall.

IMBRASE KONTRADIKSHUN5

I

I am

I am against

I am against kontradikshun

I am against those who are against kontradikshun

I am against those who are against those who are against kontradikshun

I am against

I am

I

5 In this anarchist poem, Sizwe Bantu calls attention to the anarchist poem it parodies, Zimbabwean author Dambudzo Marechera’s ‘The Bar-Stool Edible Worm,’ in Cemetery of Mind, ed. Flora Veit-Wild, (Harare: Baobab Books, 1992) and Scrapiron Blues, ed. Flora Veit-Wild (Harare: Baobab Books, 1994) and available online at <http://www.poetryinternationalweb.net/pi/site/poem/item/5862>.

The sun burns orange through the smeared windowless frame. Sweat pours off your face. The words wash over, through, in you. You begin—finally—to relax. To be yourself, whatever that is.

All the stores are closed, sealed off like the rest of this town in a heat haze, but Mrs K’s Take-Aways is open, and the smell of stale cooking oil greets you as you enter the doorway—beaded with old rusty bottle tops from glass bottles—yes, they still sell fizzy drinks in chipped bottles here. You order two ‘K Burgers’ and two portions of chips from a young woman dressed in an orange apron who stares at you as if you have just teleported from another planet. Perhaps you have. When she speaks, she throws furtive glances back at the curtain that separates the customers from the kitchen. The stilted conversation consists of the most formal of conventions. You try out your pidgin-Zulu. ‘Sour Boner.’

‘Sawubona.’ She is too polite to correct you or break out into paroxysms of mocking laughter, as she should.

‘Can you wrap one up for a takeaway … I’ll eat one here.’

She nods.

‘Any chance of a milk shake?’

‘We have run out of milk, but I can get some from the store.’

‘No, no, don’t bother, a Coke …’

You wait half an hour in a humming under-air-conditioned room. The checked red and white curtains are drawn, and the waitress bustles in the kitchen. Smoke chokes the room, and oil spits. When the order arrives she curtsies, delivers the meal on the tips of her fingers, and retreats.

You feel silly: you have watched American tourists in Australia exclusively frequent McDonalds and KFC, and putter around the Gold Coast as if it were Florida. And here, you suspect, you are moving around in a well-constructed, but poorly imitated Western orbit. So far, not much is different.

How was Africa? Zululand?

Oh, you can hear yourself saying, much the same as here.

The fat oozes from the chips, and you have to wipe your hands on your shorts, as there is no napkin. The burger, a poorly constructed skyscraper of undercooked meat, pickles and onions on a disintegrating white bun, slips and slops over the plate.

‘Wait, I’ll have those. Those are local, aren’t they?’

‘Local?’

You point to a golden doughy plait on the counter under lace and hovering flies.

‘What are they?’

Koeksisters is what they are, but you hear ‘Cook Sister’.

Your stomach regrets eating them as soon as you take the first gooey mouthful. Surely this syrupy, oil-laden heavy dough is not a South African traditional pastry? But as the waitress is watching from behind the bead curtain, you smile and eat the whole thing, nodding. ‘It’s good. Good.’

In Australia, no one leaves a tip at a takeaway. You consider that leaving a tip is a condescending insult that re-installs class hierarchy and power relations. But here, you have been told that it constitutes most, if not all, of the waitress’s wages. You leave the money on the table, but the waitress hides until you are well outside before she clears the table, and then stands by the checkered curtain watching.

Avoid isolated beaches and picnic spots across South Africa. Walking alone anywhere, especially in remote areas, is not advised and hikers should stick to popular trails.

Crowded-Planet (2013): p. 160

Some hours later (there is no need to describe the diarrhoea), you are driving down Msaswe Beach Road, gliding on fine brown sand roads into the high sand dunes, following the signs TO DA BEACH. (No, it doesn’t really say that, but it feels to you as if it should.) The image of the surfboard in the corner of the cottage (and now its manifestation in the boot of the car) has already determined your next move. The dirt road winds through the dunes for a kilometre before opening into an empty car park. You park the car on the sand area under a tree, climb over a dune and spy a deserted beach prostrating itself before the Indian Ocean. A gleaming river on your left is sign-posted Mswaswe River, its brown stream disappearing into the golden sand, and on your right, a mile or so away, another river, or large expanse of water, pools into a gap between the high dunes. You are barefoot; the sand burns into your soles; you have to dance all the way to the sea line.

Mrs Steyn’s wagging finger is not going to deter you. You’re Australian for god’s sake, as everyone keeps reminding you. Run straight into the waves. It’s slimy warm, bitterly salty, rough, and much warmer than the waters off Victoria. Gargle and spit, draw off the energy of the ocean, let the waves toss and pull you into its currents. Surf into the grainy brown sand, again and again, washing the sticky bad faith of the day’s encounters with people.

Celebrate the body.

Celebrate nature.

Celebrate the energy of this symbiotic relationship between the body and the world.

The waves are all dumpers. They pull you into a backwash and hurl you gritty-mouthed onto the ocean floor. You swim as far as you dare beyond the breakers, and then let them roll you back in. The water is murky, and only when you are floating in the calm behind the breakers do you ponder the fact that muddy estuaries make an ideal breeding ground for sharks.

Instantly, the brown water populates itself with dark shapes. The skin of the sea breaks out in dorsal fins knifing towards you; your leg brushes against the hard grey flanks of what can only be a school of Zambezi sharks—Bull sharks as they are known in Australia. In high panic, you strike out for shore but make no headway. And what about riptides, those currents that suck you out to sea instead of towards the shore? You ply your hardest, but underwater currents drag you back further than the waves can propel you forward. Your arms ache, your head throbs and your chest is ablaze. Don’t panic. Swim sideways. Don’t try to confront the current directly. Go around.

You tack sideways out of the sucking current. The dark shapes follow, encircle you. After blind minutes, you catch the surf and, propelled by a large wave which bursts into millions of particles of sand, crash onto the beach. You look back through a star-spinning haze at the sea.

Nothing like a good shark attack to throw you back to your senses.

I must stop seeing myself in the second person. I must stop seeing myself through your eyes, M I must stop seeing my ‘self’ ‘I’ must stop I must I

The dorsal fins pursuing you cut back behind the breakers, not able to come closer. You drag your heavy body onto the shore. The roaring ocean clutches at your feet and draws back with the breath of a million shells and stones and grains of sand, angry that you have got away.

You have been washed up the coast a hundred metres, at the mouth of the estuary of the ever-changing Mswaswe River. You wade across, against the current of a warm, tea-coloured tide, to a lagoon nestling in sand dunes. The sand shimmers, mirages of water stream down them, rubber green Triffids grow out of them. Wind scurries down them and dust devils whirl at their bases. You climb up one of the dunes, and roll down the other side, sticky and granulated with sand, into the lagoon. Lie in the shallow yellow water, and then swim across, slicing the skin of the red-brown depths of the lake with your hands. When you reach the far shore, a green sign with uneven white lettering glints at you. You cannot read it at this distance, so you wade closer.

IT IS DANGEROUS

TO SWIM IN THE LAGOON

BECAUSE OF

SHARKS AND CROCODILES6

6 Saussure states that the relationship between a sign and the real-world thing it denotes is an arbitrary one. There is not a natural relationship between a word and the object it refers to, nor is there a causal relationship between the inherent properties of the object and the nature of the sign used to denote it. The sign relation is dyadic, consisting only of a form of the sign (the signifier) and its meaning (the signified). Saussure saw this relation as being essentially arbitrary, motivated only by social convention.

You pull yourself out of the water, give a quick scout for nobbly crocodile backs, and wonder how far these creatures can track someone on land. You have beached yourself in a mangrove swamp. You trudge through a muddy clearing, and lopsided fiddler crabs scatter to your left and right. Mangrove trees thrust up spiky roots to trip you. Reeds crowd in around you. The smell of the earth is primeval. You have to stamp the ground to clear it of crabs who flee sideways, scuttling away into tennis ball-size holes.

You climb up and leap off a dune and onto another until you are out of the slime, gleaming with sweat and covered with coarse golden granules. Your skin tingles with the drying salt, and you feel better, much better. This is complete freedom. No one about.

It’s an odd thing: you can only be yourself when you are absolutely alone. The minute someone appears, you leap into some other self and begin acting. Why? Is it possible ever to be yourself, like you are when you are alone? Or are you still in some ghostly mask while you are alone too, unable to rip off this acting self? What is the real you, the real self that is not constructed, or habit-formed by genetics, nurture, and ecopoliticosocioshit? You don’t know. It feels good being this self, this Rousseauian free man. But perhaps the good feeling has more to do with the fact that you have succeeded in one of your selves, that you have just procured a job, wormed your way into a pleasantly secluded cottage 9,837 kilometres away and bought yourself a space in which you can be yourself, whoever you are.

* * *

The word ‘I’, like the word ‘self’, is a word that has fallen into ill-repute. There is no such thing. You initially named your doctoral dissertation ‘Constructing the African Self’ but then had to erase all the selves in it, on advice from your Lacanian supervisor. The ‘self’ is a false construct, she’d said. You have to use the word ‘subject’. And for god’s sake, stop using the personal pronoun in your academic work. Who is this ‘I’? Haven’t you realised that the author is dead, and that even if he isn’t, he does not know what he is talking about?

* * *

Your meditation, conscious as it is, is made even more conscious by the sight of a lone figure walking miles away on the dunes, watching you, as if to test you, to see what chameleon colour you turn. You are suddenly too aware of yourself, how you appear to this man. Or woman. At this distance and in the haze of the sun, you only see a stick figure. The person is walking, meandering in aimless circles, but always returning and staring out at the sea. Or at you. Reassured that you must also be an unrecognisable stick figure, you continue what you are doing, which is tracing your feet in the sand, feeling the texture of the granules, and staring at the brown haze over the sea. Then the person waves. So he is watching. Annoyed, you wave back, conscious now that you are doing what the self you are now would not do. Get lost! you want to say to this watcher, but instead you wave heartily back, to keep the peace, to show you are a friendly, fellow human being.

That evening, alone in a dark house (no electricity yet), you eat the second K Burger and chips glued together with white grease. Faint echoes of Dire Straits waft across from the house behind, but they are no match for the frog chorus at the end of the property, or the screeching cicadas on all four sides of the cottage. Animals scuffle in the bush. You strain to listen to the haunting guitar of Mark Knopfler’s ‘Private Investigations’, played with thumb and fingers.

You discard the pink sheets and lie on the open mattress, tossing and turning, listening to mosquitoes buzzing and geckos tapping on the ceiling until you drift into a haze of dead sleep. But at midnight you wake, sweat-drenched and harassed. The previous occupants of this house are still around. Whoever lived here before has imprinted his sweaty, restless nature in the air, and the room is full of ghosts.

You crawl out of bed and light the candle. The room immediately fills with shadows of hugely distorted Timothy Turners leaping around. You reach for the volume at your bedside, Bantu’s Complete Works, flip through to a page chosen at random and begin to read.

^

^ ^

“The Hermit Cockroach”

I am a spirit hovering over the water,

A soul brooding over the formless void,

Waiting to incarnate.

What is the shape of my soul?

Am I black, white? Male, female?

My soul does not wear a label,

Does not hunch its shoulders,

Does not carry centuries of programmed

Guilt or shame or degradation or complexes.

I live in the words and conventions but am NOT.

I am other.

I pretend, yes, but I am always aware that I am lying,

Humouring;

I am not my body or my roots

I am not my skin.

I am a soul, a spirit, an ageless, sexless, raceless being,

Yet I am the fullness of my sex, my race, my age at the same time.

I am uncomfortably lodged in the kontradikshun,

In a particular space and time,

Dependent on the shells I inhabit for survival;

I need to eat, sleep,

Commune,

so I husk myself until

I get too uncomfortable

And then—

I move on.

v

You blow out the candle, slap the incessant mosquitoes. No air-conditioning, no fans, no cool breeze here, just the pounding waves on the rough shore rocking you to sleep.