Читать книгу Cokcraco - Paul Williams - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

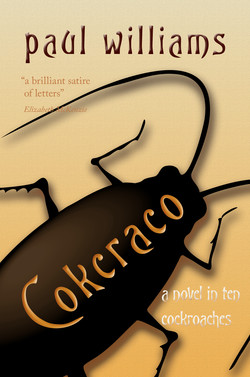

‘Cokcraco’ by Sizwe Bantu

Оглавление(The Present Tense, Vol. XXV, Feb. 2002, pp. 36-40)4

4 There has been much critical speculation regarding the title of this story. Jones (2008) maintains that the anagrammic dyslexia says much about the displacement of the ‘other’, and ‘the cockroach motif has been a favorite symbol for displaced people everywhere’. Others have made much of the missing letter ‘h’, pointing to Bantu’s commentary on how dialects of English omit the ‘h’ in speech, as in “’e ’as an ’airy back”. But the most plausible, if intellectually and aesthetically unsatisfying, explanation is documented by Wesson (2010) who points out that the original manuscfuptis of Bantu shows that he is a notoriously bad typist and contstantl;y miseplles words, as if he is typing in grtea haste. See for eample his commonly misspelled ‘form’; for ;’from’. Wesson suggests tthat Bantu was simply tryig nt otype the word ‘cockroach’ and his fingers slipped on the keys, indicating that when inspiration strikes and the words pour out ,yo udo not have the dexterity to keep up. Elsewhere in his manuscripts, we see cockroach spelled ckroahc, cokroahd, and even codchroarh.

In the city of Durban, KwaZulu-Natal (in the imaginary country of Azania, Afrika) a man rented an apartment near the beach, in a derelict but expensive neighbourhood behind Point Road. In Apartheid days, the area had been a whites-only area—and was still largely whites-only due to the exorbitant rents set by unscrupulous and invisible landlords. (I’m only talking of the insides of the apartments, of course: the streets were the habitat of prostitutes and street children.) The man—let me call him a Modern Afrikanist for now—who rented the flat lived alone.

The flat afforded a sea view, or so the landlord had told him. The apartment block was crowded in with other dilapidated buildings, but if he craned his neck out of the kitchen window on a clear day, he could see a blue patch of sea between the Nedbank towers and The Wheel. Taxi-drivers, prostitutes and street brawlers below made the street a noisy place at night, but once he had bolted and double-locked his front door and slammed the street-facing windows, the Modern Afrikanist would be left in silence to pursue his artistic endeavours.

5 Although Bantu here refers to the African or Oriental cockroach (Blatta orientalis), scholars have agreed that the cockroaches in his paintings and sculptures are more likely to be the death-head cockroach (Blaberus craniifer) because of the striking markings on the thorax.

Unfortunately, the main feature of this flat was not its privacy, nor its silence, but the scuttling of serrated legs and rasping of carapaces against the linoleum. In Durban, cockroaches grew three to four inches long.5 He would find them everywhere: when he turned on the tap, they shot out; when he made tea, he found them dead and soggy in the kettle; when he poured cereal, he found them sleeping disguised as Honey Smacks … He didn’t like squashing them—they made such a mess. Instead, he spread toxic white powder for them in the kitchen cupboards; he plugged up the taps; he sealed his food. But they kept coming. He resorted to spraying the crevices, cracks and running boards every morning before he went out. He would return at night to find piles of cockroach corpses in the bath, on the kitchen table, in the bed, and lining the skirting board to every room.

His initial repugnance soon grew into a hesitant fascination for these armies of determined creatures, who by their suicidal insistence claimed residence here. Over supper (Bunny Chow bought from The Star of India downstairs), he found himself staring at a particularly large dead cockroach on his dining room table. Its jagged legs, its oval shape, the light reflecting purple and orange off its back spoke to him. I am black, but comely, it said. Behold, I also am formed out of the clay. He was particularly intrigued by the black marking on its head, a third eye watching him from another dimension.

He was suddenly ashamed. The Modern Afrikanist was an artist: he prided himself on an aesthetic appreciation of the world: so why should he exclude cockroaches from his artistic apprehension of the universe? They had value. They had form. They had beauty.

So instead of brushing away the dead cockroach in disgust, he set up easel and paints on the table and painted its portrait, with garish Fauvist colours, and generous gobs of paint, smeared on with the gusto and urgency of Van Gogh.

Pleased with his evening’s work, he hung the picture on the living room wall. The next day, after breakfast, he shaped in black modelling clay a giant Rodin representation of the dead creature. And as he was loath to throw away the cockroach corpse, he varnished it with lacquer, and set it on the mantelpiece under his painting.

From here on, he no longer swept away dead cockroaches, but collected and sorted them according to size, texture, colour, and death-posture. He pasted the tiny ones onto a canvas and painted them —bright blue, orange and green—into a landscape, and hung the work of art on the wall in his kitchen. Monet would be impressed: up close, the painting was a knobbly packed death trench of cockroaches; from a distance, it was the North KwaZulu coast line, with sweeping, wavy cane fields, complete with workers dotted in the stalks, and smoke rising in the distance where old cane fields were being burned.

He glued the large cockroaches along the rim of his bookcase to make a pleasing pattern of ridges and bumps, taking care with the feelers so they would form a pattern of aerial lightness.

As more and more cockroaches died, he created more works of art. In a few short weeks, his furniture was covered with varnished cockroach designs, seven magnificent paintings hung on his walls, and a trinity of three large statues sat on his tables in raw clay, an essential gesture of cockroach emerging out of the formlessness of his previous prejudices. Soon there were no more walls to use: he covered his lampshade with cockroach designs; he made a sofa cover from the smooth corpses of cockroaches; he covered his desk with the oval pattern; he pasted them all over the bookcase. He now loved cockroaches—their form, their slender shape, their nestling together. A dozen new projects spun from his mind onto paper in the middle of the night—a cockroach-paste sculpture, a cockroach doorway, a cockroach carpet, a cockroach Azanian flag.

Ironically, as the months passed, he ran out of cockroaches. Either there were no more in the dark spaces behind the walls of his flat, or they had got wind of his intentions, and had migrated to better homelands, where there was more to eat, and where macabre, varnished corpses of their brothers and sisters did not stare at them from walls and bookshelves and headboards.

But the Modern Afrikanist was still bubbling with inspiration; and so he went out in search of raw material. He scoured the rubbish containers at the end of the street and collected roaches in plastic bags lined with white powder. He frequented the back end of The Star of India restaurant, the stench of a make-shift toilet behind the shish-kebab stall on the corner, and the stair wells of his apartment building. He arrived home every evening with his bag full, sorted them out by shape and breed (Asian, Smoky-Brown, Parktown-Prawn black), glued broken feelers on the big ones, repaired broken wings, legs, and carapaces, then set to work.

The paintings were beautiful: here is one of the Indian Ocean he couldn’t quite see from the kitchen window, clear skies, zero humidity, the brown smog that skulked over Durban vanquished; here’s another of the street below, devoid of prostitutes and taxis and street gangs, replaced by a post-Apartheid rainbow community of people; and here is a self-portrait of a clear-faced, hopeful Modern Afrikanist, looking out onto the horizon of the Afrikan Renaissance. Each painting breathed hope into the world.

The heat is hellish.

The car is protesting as you drive onto campus. Its needle strains way into the red, its fan whines, its engine stutters.

And you’re late.

You follow Alice-in-Wonderland signs that coax you around roundabouts to Building D: HUMANITIES. The English Department is on the second floor.

You park in an empty lot, adjust your tie, gather your belongings and walk smartly towards Building D. You hunt first for a toilet. You need to rearrange yourself, compose yourself, straighten the crumpled suit, splash the fear off your face.

Here’s one on the first floor. GENTLEMEN: STAFF ONLY. But the sign has been mutilated with a knife, and a palimpsest has been scrawled over it in black pen: THE DOORS OF ABLUTION BLOCKS SHALL BE OPEN TO ALL.

You hunt in vain for a mirror but find instead four screw holes on the wall and a dark patch where a mirror has been removed. The water from the cold tap comes out scalding hot, and the hot water tap produces cold water.

The sweat has dried on you to a lacquer finish, a thin varnish of fear glazed onto your soul.

Your body always betrays you. Every time. But stick it in a suit and tie, itchy grey socks and black leather shoes, crisp shirt and collar, and you can disguise its animal nature well enough.

The long English Department corridor smells of smoke and burnt rubber. Half way down the passage, you pass a gutted office—and stop to peer in through a dark black hole where the door has been beaten in with an axe. The gold plaque on the door, blackened but still legible, reads DR THAMI MPOFU, ENGLISH.

You take out the printed copy of the email you have folded tightly in your pocket and squint at it in the bad light.

Hi Timothy

Shall we say, ten am on the 15th? Let’s meet in my office.

Building D, second floor, left along D corridor.

You can’t miss it.

Thami Mpofu.

Yellow tape criss-crosses the yawning cavity, and inside, the entire office is burnt out. What were once plastic blinds on the windows are now curled molten blobs of black dripping down the wall onto what was once a desk. Empty bookshelves stand charred against the wall. Just your luck. Come all this way and the guy’s been burnt to death in his own office. You walk past many shut doors, heavy oak stout doors with sombre signs labelling them as Professor, Doctor, Lecturer, Adjunct Temporary Tutor and so on. At the far end of the corridor, you spot the door you have been looking for: Professor J. Zimmerlie, Acting Chair.

In any other universe, you would wonder what the hell an ‘Acting Chair’ is.

You get the impression that they are watching you on CCTV, though you have seen no cameras, for even before you knock, the door opens.

‘Professor Zimmerlie. Dr Turner is it? Glad you made it.’ The man offers a limp yellow hand for you to shake.

The umlungu is dressed in a tight dark suit, white shirt, tie, cufflinks, shiny leather shoes. He is the whitest man you have ever seen. And you mean that literally. He is so white, he looks geckoish. And good god, you stare—try not to stare—at the stitches on his head, scars now, faded pink Frankenstein stitches about two centimetres long, neatly caterpillared across his left temple.

Behind him, another man thrusts out his hand. ‘Hi, I’m Mpofu. Thami Mpofu.’

He is the opposite of Zimmerlie, if people can be opposites. He exudes a healthy dark glow, and grins with a self-confidence that you see can never be shaken.

‘Ah, Professor Mpofu. I … your … office … ?’

‘My office is temporarily indisposed,’ says Mpofu.

‘There was an accident,’ says Zimmerlie. ‘A fire.’

You detect a flicker of embarrassment between them. No, more than embarrassment: a lie.

‘We Zulus have a saying,’ says Mpofu. ‘Khotha eyikhothayo … The cow licks the one that licks her. John has kindly let me use his office and facilities.’

Zimmerlie presses his fingers together. ‘Thami has an apropos proverb for every calamity.’

They speak like one creature, a two-headed monster. Opposites, but twinned, symbiotic opposites.

‘Come in, come in.’

The walls of the office ceiling are plumped with books, framed certificates, photos. The Journal of Southern African Literature. Leavis’s The Great Tradition, Harold Bloom, Kristeva, Derrida, Barthes, Foucault, Saussure, Structuralist Poetics. The books speak for themselves. You are now entering the world of Literary Criticism, another world, another language. And there are shelves of literature, too, with a capital L: The Collected Works of Chaucer, Shakespeare, John Donne, The Romantic Poets, Thomas Hardy, DH Lawrence. Be warned: this is the world of Literary Criticism, and these are Literary Critics.

A LITERARY KRITIK

KritiK: a person who rubs his or her legs together to make a noise. Not to be confused with a KriKit, the singular of the game played with a bat and a ball by humans dressed in white. Not to be confused with a KoKroach, another hardy insect that has outlived the dinosaur, and doesn’t Kriticise anybody.

KritiK: Arch enemy of writer.

A strange thing, a literary KritiK. Always seKondary. Though KritiX themselves do not think like this. KritiX always trail behind writers, mopping their words, examining their faeces for meaning, signifiKance, signifers and signifiers. Would it not be better to be the writer yourself? Maybe that’s what KritiX are, failed writers, wanna-be writers, and this whole industry of literary aKademia is a green pool of envy and failure. The right brain telling the wrong brain what to do.

But we shouldn’t disparage them: they’re a dying race, and no longer have anything to feed off. XtinKt. Once they bred in the sewers of universities all over the world, and now all we have are their empty KarKasses. No one reads anymore.

— Sizwe Bantu, Seven Invisible Selves, 2008

The window looks out on an idealised African image: rolling green hills, dotted with grass huts under a deep blue sky.

They haven’t let you speak yet. You put it off as long as possible, rehearsing the words, slowing your breathing down. The sweat has dried sticky and cold on your skin in the arctic air-conditioning in the room.

‘Sit, sit. You must be tired. How was the trip?’

You sit. Consider. Should you tell them about the sixteen-hour flight, the Durban hotel you stayed in the night before adjacent to a shebeen that played loud music to the early hours of the morning, the air-conditioning in your overpriced rental car that didn’t work, the last few minutes of terror when you were sure you’d be dead?

‘It was fine. No worries.’

‘No worries? I like that.’

‘He’s Australian. Australians don’t have worries.’

‘Australians have a sense of humour.’

‘You’ll need a sense of humour to work here, Dr Turner.’

‘Tim. Call me Tim. Or Timothy.’

A suit does wonders. Paste a self onto your shimmering non-being, and people believe you to be solid.

‘You’re replacing a man who has been suspended from office,’ says Mpofu.

‘It’s been a terrible business.’

‘As we Zulus say, Umlomo, ishoba lokuziphungela.’ He offers no translation this time, but you nod anyway. You do a lot of nodding. The puppeteer up there in your brain jerks the head string way too often. But that is what humouring is.

The differAnce between pretending to be what people wAnt you to be and humouring them by Acting in a certain way is quite indistinguishable. Always mAsk; AlwAys pretend; AlwAys protect yourself. But don’t inhabit the mAsk. Don’t feel inferior: only Act as if you Are inferior. Be deferentiAl, but don’t yield.

– Sizwe Bantu, AfriKan Metaphysics, 2007

Zimmerlie sighs. ‘He’s fighting the case, of course. Suing the department, the university, has even made a personal case against each of us.’

‘The case could go on for months, years …’

‘A delicate issue,’ says Zimmerlie. ‘We shouldn’t talk much about it.’

‘The less said the better.’

‘There’s a trial, an inquiry, an investigation.’

You have to ask. ‘Who … ? Who are you talking about?’

‘Makaya.’

‘A horrible man.’ Zimmerlie holds up an enormous weight of air with his hands to measure, you guess, the enormity of the horror. ‘It may be a semester, or perhaps longer—we just don’t know—because now he’s refused to accept dismissal and there’s a board of enquiry—and he’s taking us all to court …’

‘Dr Turner, if he is fired, there’ll be a permanent post here and there’s a good chance you’ll get it—we didn’t want to bring you all the way from Australia for nothing.’

‘What’s this?’ Mpofu takes the blue-bound thesis from your hands. ‘The novels of Sizwe Bantu?’

‘My doctoral thesis, in case you’re interested, is on the novels of Sizwe Bantu.’

They don’t seem to be, so you offer more: ‘You know, the author who made himself famous venerating the cockroach.’

Blank, unreadable faces. Zimmerlie’s furrowed eyebrows. Mpofu licking his lips. Go on, prod their memories. ‘African International Book Prize. Nova Award?’

Zimmerlie takes the thesis from Mpofu and riffles through the two hundred pages as if it is an animation flick book. ‘Interesting.’ He hands it back without reading a word.

Mpofu speaks in a tone that can only be interpreted as patronising. ‘He’s a rather contentious writer around here.’

Don’t react. Don’t. Don’t gawp in amazed disbelief. Grit your teeth. Smile. ‘Oh, really? Contentious?’ Don’t say: Sizwe Bantu is the Greatest African Writer of All Time.

‘Not very well thought of around here,’ adds Zimmerlie.

Don’t say: he lives around here. Surely you know him, honour him revere him, even just as a local writer?

Surely Bantu?

For this is Bantu territory. The hills you can see through the window are the hills pictured on the cover of Bantu’s third novel, Seven Invisible Selves.

But of course—and you should know this—people are blind to talent in their own backyard, and a prophet is never recognised in his own country.

An embarrassing unpleasantness hovers over you, like the smell of a gutted office and burnt rubber. Silence. The swallowing of thick Adam’s apples.

Zimmerlie claps his hands together to banish whatever bad spirits have entered the room. ‘Well, Timothy, Thami and I have some business to attend to with Admin regarding your appointment. Why don’t you stroll around campus and get a feel for it, and return in, say, half an hour?’

* * *

The idea of a quick campus tour is quashed the second you step out of the air-conditioned English Department. The air blasts your face like a furnace, and the sour humidity curdles your stomach. Have you forgotten so quickly where you are? The sun dazzles every reflective surface; you swear that the tar under your feet is melting. And there is not a soul out of doors. The air-conditioning units on every corner of every building roar; what must be cicadas compete from low grey bushes. It is not a place to be outside at midday.

And—an aside—why the colonisers named this the Dark Continent must have been some kind of joke. It is full of light everywhere, refracting off all surfaces. It is drenched in sunlight. And the land is green. Fertile. Fecund. Fruitful. The jacarandas here are really purple, not like the insipid pastels back in Victoria. And the poincianas are magnificent trees with blood-red dripping leaves.6

6 Footnotes are tiresome things, interrupting the reader’s ‘jouissance of the text’ (if any) and plunging his or her eyes down to the bottom of the page to read some unnecessary and distracting, often self-consciously arrogant ‘extra’ but vital information added by the author. Look at me, they (the words) shout, or worse, look at ME (the author). Even more annoying is when they spill onto the next page. Ironically those who argue for the use of footnotes are those who maintain that they (the footnotes, not the people) are there to avoid disruption of the flow of the main narrative. They are most common in academic works, where terms need to be explained, or outrageous claims need to be justified, or irate or confused readers need help. The idea is that they can be ignored. Ha! Just try to read past one of those little numbers, and you are distracted, the flow of your narrative jouissance is stopped in its tracks, and you have to see what it is that the author has deemed so important that you have to halt your reading and find the corresponding number at the bottom of the page. Thank god, you say, these are not end notes, or hyperlinks.

You pace the sparkling cinder-paths, determined to get a perspective on the place. Each building—science faculty, arts block, Admin, each lecture hall—has been magnificently designed. The Admin block even has turrets, towers and flying buttresses. The science block is a cool, modern green—enormous slabs of concrete and sweeping open stairs lead up to large sliding glass doors. But each window, each glass-fronted door, is obscured by an intricate brick breeze-block pattern, as if to stop people looking in or out.

You savour the idea: this is a university, a place of the mind, and more, it is an African university, twelve thousand kilometres away from everything you were not, and twelve thousand kilometres closer to someone you will become.

You reach a green park, neatly squared off and labelled ‘Freedom Square’, its benches slouching against shady trees around a perimeter of buildings, and decide that this is the centre, the focus of the campus, a good place to stop and get perspective on the place.

Beyond, you can see Bantu’s bumpy and hazy hills, huts and dust. Freedom Square—a place where no doubt some bloody history—demonstrations, water cannons, tear gas, police baton charges—occurred, where students, vanguards of the revolution, wrestled their freedom from the Apartheid regime. The Doors of Learning Shall be Open! You saw the grainy news clips on TV as a child—but today, the square is sterile, empty, barren. The struggle, it appears, is over.

A scraggly, fur-matted, mewing kitten presses against the metal leg of the bench. You bend down to pet it, but it scratches your beckoning hand and runs off into the grey-green bushes behind. You observe with cold horror that its eyes have been gouged out.

In the centre of the square, signs point in higgledy-piggledy directions to Bekezulu Hall, to the Sports Field, to LAAC (whatever LAAC is), to the Staff Tearoom, Student Services. But you are seduced by the one pointing to the library. The humming machines promise sweet cool air, and you are dripping with sweat. You push through the glass doors. Inside, a vast open-plan dome, like a church, opens out. Very air-conditioned.

The library is empty. No students anywhere. But staff librarians quietly shuffle behind glass-walled offices. One woman at the checkout counter looks up as you pass her desk. You meander through the corridors of books, and then sit at a catalogue computer. You type in ‘Sizwe Bantu’.

Search results show that this university has all Bantu’s major works, in hard copy and electronic form. The Great South African Novel (2006), AfriKan Metaphysics (2007), Seven Invisible Selves (2008), The Five AfriKan Senses (2009), The Cockroach Whisperer (2010), and Cokcraco and Other Stories (2011).

Whew.

But when you search for availability, all of them show up empty. Withdrawn. Unavailable. Missing.

i Yam the cockroach who everyone ignores.

i Yam the loud fart in the elevator everyone pretends did not happen.

i Yam the spot on the teenager’s nose just before her first date.

i Yam the disembodied obscenity scratched on the wall of the church.

– Sizwe Bantu, AfriKan Metaphysics (2007)7

7 The reader will recognise several plagiarised/sampled/intertextual references, this time to Zimbabwe writer Dambudzo Marechera’s poem ‘Identify the Identity Parade’ in Cemetery of Mind, ed. Flora Veit-Wild, (Harare: Baobab Books, 1992): ‘I am the loud fart all silently agree never happened’. The phrase ‘Disembodied obscenity’ is taken from Njabulo Ndebele’s story ‘Fools’ in Fools and Other Stories (Readers International, 1986). Words, Bantu is saying, are all borrowed, recycled, used up, and all we can do is rearrange them

* * *

‘Ah, Mr Turner.’

Mpofu hands you a document, stamped and signed. ‘As we arranged over the Skype interview, Admin are very agreeable to a twelve-month contract for starters. And as soon as our little problem is cleared up, we can advertise a permanent position. And if we play our cards right, you could get it.’

‘Thanks.’

A moment’s hesitation.

‘A word of warning … we’d be amiss if we didn’t say …’ A lightning glance at Zimmerlie; a slight nod in return. ‘You know you’re walking into the lion’s den?’

It is not difficult to guess what they are going to say next. ‘You mean Makaya … ?’

Zimmerlie nods. ‘Makaya is a dangerous, vindictive man. When he hears that you are taking his position …’

‘The political minefields in this campus are complex, Timothy, very complex. We have to watch our backs.’

‘We want to protect you from the kind of spiteful attacks that occur on this campus in the name of academia.’

Are you surprised? Where have you been anywhere in the world where spiteful attacks in the name of academia do not occur? But you widen your eyes appropriately.

‘We need someone to take over a very restless class of one hundred first-year students who have been left in the lurch and messed around by … by …’

‘That recalcitrant man.’

‘And the Honours class is … how can we put this? Rather … belligerent.’

‘Aggressive.’

‘Makaya tossed all textbooks out of the window. He had got them doing silly creative writing exercises instead of studying real literature.’

‘That’s the urgency. You could start on Monday?’

‘Yes, of course.’

‘Of course,’ says Mpofu. ‘He has all sorts of questions. Salary, accommodation, syllabus.’

‘The details we can arrange later. The important thing is—you can start Monday, get those students off our backs …’

‘Where will you be staying?’

‘Not sure. I was thinking of eSikamanga?’

Zimmerlie frowns. ‘Thami lives in Assegai, thirty k’s north, as do many of our faculty. A large city with all the modern conveniences.’

‘Professor Zimmerlie,’ says Mpofu, ‘lives in eSikamanga. He loves it there. By the sea. A small town right on the Indian Ocean, about thirty k’s south. Those are your choices. I can put you in touch with an estate agent … ?’

‘That would be good. How are the waves?’

Zimmerlie nudges Mpofu. ‘I told you he was an Australian. Now … I know this is very short notice, Timothy, but there is a requirement of any new faculty member to … to … er … present a lecture to the staff and faculty of the university, to introduce yourself, as it were.’

‘Sure. I can do that. When?’

‘Is next Friday too soon?’ Zimmerlie wrinkles his brow.

‘No worries.’

‘Marvellous! And do you have a topic?’

‘I will. Probably something like … “Playing with Words while Afrika is Ablaze”?’

‘Intriguing. And you can have this ready for next week?’

‘Yep. Too easy.’

Zimmerlie clears his throat. ‘Is that a yes?’

* * *

You march down the dark corridor to the EXIT sign armed with The Complete Works of Shakespeare, Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales, Modern African Stories, a solid phalanx of literature to teach. The gist of it is, Makaya neglected—even dropped—literature from the syllabus, and taught instead Creative Writing. And you are here, so you gather, to put that all right.

It is no matter. You don’t care what you are teaching. You have already decided to humour these men, to glide along over these matters. Makaya, for all you know, might be quite a decent bloke. You are determined from the outset to remain above it all, as neutral as Switzerland, as wry, ironic, as Bantu himself, unsullied by politics of the academy.

But your sense of wellbeing is short-lived. A door to the left swings open, and a short, stout man bursts out and sends you sprawling. The books Mpofu has given you thud on the red polished floor. The man reaches out a hand to help you up. ‘Sorry, didn’t see you there, china.’

Double take, then smile, as if this is normal. The man has orange hair. You cannot stop staring. ‘Turner,’ you say. ‘The new replacement lecturer.’

The man pulls his hand away as if he is afraid of catching some contagious disease. ‘Wena?’

You scoop the books off the floor to make a quick exit. But it is too late. The man has seen. ‘Shakespeare? Chaucer?’

‘I’m teaching Shakespeare, yes. And Chaucer.’

‘Dead white males? To African students who are trying their hardest to throw off the shackles of colonialism?’

How do you respond to a loaded question? Point the gun away from yourself. You indicate the closed door at the end of the corridor. ‘Professor Zimmerlie …’

‘Zimmerlie!’ The man uses the word as an expletive.

‘Yes, Zimmerlie. And Mpofu.’

‘Mpofu! I should have guessed.’

‘And you are … ?’

The man ignores your outstretched hand and shoulders his way down the corridor. His footsteps echo past the series of dark office doors, and at the end of the hallway, framed by a halo of light, he turns and squints back into the darkness, sunlight setting his red hair on fire. ‘Bastards.’

It looks, on your first day, as if you have inadvertently made an enemy.

COCKROACH INTERVIEWER: Why do you not like humans?

COCKROACH: Humans are nasty pests, known for their insatiable greed. These parasites will feed on other animals as well as their own kind. Once they colonise a territory, it can be a real challenge to eliminate them. Humans carry many toxic diseases and leave a trail of destruction wherever they go. Their love of turning pristine wildernesses into sterile concrete nests and burrows is well documented.

– Sizwe Bantu, The Cockroach Whisperer, 2010