Читать книгу Harold Wilson - Peter Hennessy, Ben Pimlott - Страница 11

Оглавление3

JESUS

In Oxford terms, the small college of Jesus was a backwater, which did not attract the ablest pupils from the most prestigious schools. Harold was told before he went up that it was ‘despised in Oxford’.1 Even Wirral Grammar School regarded it as second best. Its strongest traditional link was with Wales, though there were also many boys like Harold – especially among award-winners – who came from the North.2 Expectations among Jesus men were appropriately modest. Many became clergymen, schoolmasters or provincial lecturers. The ablest joined the Civil Service (the Home, not the Diplomatic), though the number of such entrants was barely more than a trickle, and averaged only one per annum in the inter-war years.3 The college’s best-known pre-war alumnus was the legendary T. E. Lawrence, ‘Lawrence of Arabia’. Wilson is the only inter-war Jesus student to have achieved a general fame.

The unpretentiousness of Jesus made it relatively easy for the product of a provincial grammar school, and a relatively humble home, to adjust to the life of a tradition-bound university. It also meant that Wilson did not automatically rub shoulders with Oxford’s undergraduate élite. In this respect, his experience was different from that of some others who became Labour politicians after the Second World War, for whom Oxford was an entry-ticket to the governing class, if they were not members of it already. Hugh Gaitskell, Douglas Jay, Richard Crossman (all at New College), Frank Pakenham, Patrick Gordon Walker, Christopher Mayhew (at Christ Church), Denis Healey and Roy Jenkins (at Balliol) shared staircases and ate dinners from their very first term with well-connected, well-off young men who already had a confident view of their own place in the world. Harold did not find himself in such society and did not seek it. Throughout his days as an undergraduate, he was singularly indifferent to its activities.

Instead, he remained contentedly part of the other Oxford: the Oxford treated contemptuously by Evelyn Waugh in Decline and Fall and ignored completely in Brideshead Revisited. There are very few novels about Harold’s Oxford. Perhaps there should be more. Harold’s friends, however, did not end up writing novels. The other Oxford was dedicated to essays, marks, exams, chapel-going, sport and college societies at which learned papers were read and discussed. It was the Oxford of the overwhelming majority of undergraduates, not just at Jesus but in most other colleges as well. Harold differed from fellow members of this Oxford only in the ferocity of his determination to do well academically, and the remarkable extent of his success.

Harold’s letters home to his family, of which many survive from his first two years, provide a fascinating glimpse of the preoccupations of his early manhood years. They are not dramatic: what is noteworthy about them is how little they contain that is unusual, or might not have been written by hundreds of contemporaries who disappeared, after graduation, into anonymous staff rooms and parsonages. They reveal a highly conventional young man deeply absorbed in the formal experiences of university life. They show him stirred, sometimes movingly, by the intellectual ambitions, and casual presumption, of Oxford, and the opportunities the university provided for him to stretch his own capacities. They do not indicate any need or desire to stray beyond the bounds of officially approved learning.

What is going on in a young man’s head and what he tells his parents need not, of course, be the same thing: but there is no guile in his writing, much of which has a child-like quality. The letters deal mainly with wants, and how he is coping. They are about money – how much he has, how much he needs, how much things cost, and how he is making ends meet, often down to the last penny. They are about food and other provisions, to be purchased at Wirral rather than Oxford prices, to supplement meagre college rations; about tutors, lectures, societies, sport, his own unquenchable thirst for parental letters; and they are about Gladys. They are, by turns, warm, generous, demanding, winsome, boastful, witty, self-possessed. Though they are sometimes lonely, they are never anxious. They are forever looking ahead, planning moves in Harold’s own life, and organizing his parents to do things on his behalf, in the confident knowledge that they will comply. They are uncomplicated and loving. They present Harold as, already, a man content with who he is, where he comes from, and the upward direction in which he is heading, fighting battles on his own, with no need for backing other than the support he takes for granted from his family.

At first he was homesick. Unlike Gladys, with her experience of boarding-school, Harold had never lived away from his parents, except during his illnesses and at Scout camp. His early letters – lengthy and poignant, stressing the lack of home comforts – are full of characteristic symptoms. The contents of Harold’s laundry feature prominently: it had been agreed that he would send this back to Bromborough to save money. ‘I think that for the first fortnight’, he wrote on arrival, ‘I’ll just send my collars, hankies, vests, pants and socks.’4 He explained: ‘The reason there are so many hankies is that I have a bad cold.’5 Another letter suggested: ‘It might pay to send butter (it is very dear here) next week with washing, also two oranges.’6 To Marjorie he wrote: ‘Will you please send me a 6d. meat pie? I’ll send you the cash in my next letter.’ Was he all right, were the other chaps OK? asked his sister. He was happy, he replied. ‘That’s the answer to I of your questions,’ and to the other, ‘Yes, very decent set. No snobbery.’7 He had been placed in a first-floor room with a young Welsh Foundation Scholar, A. H. J. Thomas of Tenby. ‘He’s an exceptionally nice fellow & we seem to have similar tastes’, wrote Harold, ‘– both keen on running, neither on smoking or drinking, and have similar views on food, etc.’8 To illustrate the satisfactoriness of the Wilson–Thomas set-up, Harold drew a careful sketch-map of their joint room, showing its furnishings, and with a numbered key.

In search of company and familiar surroundings, Harold responded to an invitation to join the University Congregational Society, and got to know Dr Nathaniel Micklem, Principal of Mansfield, the Congregationalist Theological College. He also took an interest in the evangelical Oxford Group, which had many Nonconformist members. ‘Am enjoying the Group, it’s the only thing I’ve seen more than skin-deep,’ he wrote at the end of October, having had little luck with the political clubs.9 Both the Group, which offered secular as well as religious discussions, and Mansfield, became focal points. He often attended Sunday morning services in Mansfield Chapel, as well as evensong at Jesus. Later on, he sometimes accompanied a friend to Sunday evening concerts in Balliol chapel to hear the undergraduate Edward Heath (whom he did not yet meet) play the organ.10

Voluntary chapel-going, beyond what his own college required, became a reassuring part of his weekly routine. ‘There was a deeply religious element in his make-up which influenced much of his political thinking in later years,’ considers Eric Sharpe, a friend and contemporary at Jesus who attended services with him and later became a Baptist minister.11 Harold made much the same claim. ‘I have religious beliefs, yes’, he told an interviewer in 1963, ‘and they have very much affected my political views.’12 Mary does not quite agree. ‘Religion was part of his tradition,’ she says. ‘He never questioned it, but he did not think much about wider religious questions. When he did, he believed that people should translate Christianity into good works.’13 Labour colleagues, mainly atheist or agnostic, viewed Harold’s piety with cynicism. Set against his cat-like manoeuvrings at Westminster, it looked like humbug. Nevertheless, religious worship was part of the mould which formed him, his political outlook, and his idiom.

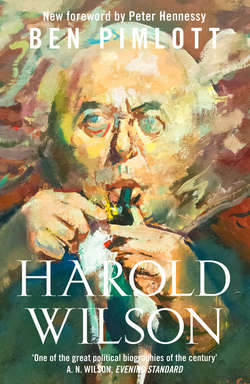

Harold’s sketch-map of his room at Jesus College, and its location.

At Oxford, religion and politics were often mixed. He used to go to a Congregationalist discussion group called the Dale Society on Sunday afternoons, to hear speakers who examined the link between faith and action. He frequently intervened. ‘He spoke with clarity and force,’ recalls another Jesus contemporary, Professor Robert Steel, who matriculated also as an exhibitioner in the same year. ‘He could put a case in a very persuasive manner, and unless you felt strongly you accepted what he said.’ One popular topic at the Dale Society was the colonies – in modern terms the Third World, a topic in which Harold took a special interest. ‘If someone gave a talk on the race problem, the chances were he would go to it,’ says Steel.14 He took an active interest in college discussion societies, becoming president of a couple of them. The college magazine records that in 1936 he addressed the Henry Vaughan Society in Jesus on ‘The Last Depression and the Next’ and caused offence to a former president of the society by referring to ‘“mugs” on the Stock Exchange’.15

Harold’s greatest solace was work. As a history undergraduate, he had to take prelims at the end of his first term, based on set books which included works in medieval Latin, and an economics textbook, Public Finance, by a former LSE lecturer called Hugh Dalton. Though the pass standard was not high, the quantity of material was large. ‘I doubt if I have worked so hard in my life,’ he said later.16 He was an early riser. Steel used sometimes to meet him in the bath house before breakfast – he would be conscious of Harold’s presence because his friend would sing the same songs repeatedly, at the top of his voice. He also used to see him regularly at dinner, where they sat together at the exhibitioners’ table. ‘Harold used to study a great deal, and then have a glass of beer,’ recalls Steel. ‘We all knew that he coped very well with essay writing and that he read voraciously.’17

Apart from the occasional beer, there was little time for anything else, except sport. At school he had been a keen long-distance runner. At Oxford he played football in the college second team, and tennis, even in winter. But athletics was his real passion. He ran on the Iffley Road track most afternoons. ‘He had an obsession about physical fitness,’ says Sharpe.18 He was a half-miler, though he sometimes ran longer distances as well. One such occasion, described in a letter, occurred in his second term. ‘I’ve some very good news,’ he wrote to his parents:

Just after breakfast this morning (Saturday) the cross-country captain came in & asked me to run for the Varsity Second Team v. Reading A. C. (I tried to send you a p.c. so you would know Saturday night, but couldn’t catch the post).

Well I ran: I started badly & after 2 miles was 14th out of a field of 16. After we had topped Shotover Hill, I got my second wind & moved a lot better. I caught up 7 places in the last mile – & finished 7th (the third Oxford man home…)…

After that we were taken in a motor coach to the city & had tea in a very posh restaurant – all of us on one table in a private room: the captains made speeches etc. I felt very thrilled about it all. So I’ve represented the Varsity. If I could only get my cross-country really well up, I might get my half-blue next year.

… Still feeling very thrilled; hope you’re also duly thrilled.19

Active politics – the precocious dream of his adolescence – had a lower priority. Nevertheless, the interest was still there. In his first week, he joined the League of Nations Union, and was approached by the Secretary of the University Labour Club, ‘a very decent fellow from Wallasey’. ‘I think I shall join the Lab. Club’, he wrote home, ‘– the sub’s only 2/6. I shan’t go to many meetings, just to those addressed by G. D. H. Cole and Stafford Cripps I think – both this term.’ He joined the Oxford Union on similar grounds, ‘partly on account of debates, hearing important men – Cabinet Ministers etc.’, but more because of the library.20

He made extensive use of the Union to take out books and as a place to work, and attended debates without taking part in them. The Labour Club, however, was a bitter disappointment. His first experience of it put him off. It struck him, he wrote home after attending a meeting a few weeks after going up, ‘as very petty: squabbling about tiffs with other sections of the labour party instead of getting down to something concrete’.21 Many years later, as a well-known politician, he elaborated on this point, maintaining that he ‘could not stomach all those Marxist public school products rambling on about the exploited workers and the need for a socialist revolution’.22 This became his standard excuse for not having taken part in Labour politics as a student. It was also a way of indicating to people who equated Bevanism with Communism that he had never belonged to the fellow-travelling left wing, while giving a side-swipe at the Labour Party’s upper-middle-class intellectuals, many of whom had started on the Left before moving rightwards.

The obvious explanation for Harold’s lack of political involvement in his first term was that he was not sufficiently interested and, with an exam a few weeks away, he had too much to do. These points are made in a very early, pencil-written note home, which accompanied his first laundry parcel, before he had yet attended a single Labour meeting. ‘Cole is speaking at the Labour Club to-night but I don’t think I’ll go,’ he wrote. ‘I’ll wait till next term for that sort of thing.’ He added a sentence which indicated the first call on his attention, after work: ‘I’ve been running twice at Iffley Road – nice track.’23 Yet the reason he gave later is also convincing. For his arrival at Oxford happened to coincide with a moment in undergraduate politics when the student Left was as febrile, and as out of touch with reality, as it ever became in the course of a heady decade. The Labour Club in 1934 was the crucible of fashion. But fashion was something to which Harold, sometimes to the irritation or scorn of contemporaries, was unusually immune.

‘In recent months there have been unmistakable signs of an increase of political consciousness amongst the undergraduates of Oxford and Cambridge,’ one observer noted at the beginning of 1934, before Harold went up, adding that political activity had been ‘largely confined to socialists and, to an increasing degree, to communists.’24 By the time of Harold’s arrival, a fertile generation of left-wing undergraduates that had included Barbara Betts (later Castle), Anthony Greenwood, Richard Crossman, Patrick Gordon Walker and Michael Stewart – all future members of Harold’s Cabinets – was just ending. But the memory of them was fresh. ‘Consciousness’ was the vogue word. ‘Oxford was very, very politically conscious,’ recalls a friend of Barbara Betts.25 An important raiser of consciousness, and prophet of Oxford socialism, was G. D. H. Cole, an ascetic thinker whose First World War semi-syndicalist ideas had given way to a Fabian, pragmatic approach, though still with a Utopian goal. In 1930–1, Cole had gathered together a group of young disciples at Oxford which included Hugh Gaitskell, a WEA lecturer who had recently graduated from New College, to help set up two closely linked ginger groups or (as they would now be called) think tanks: the New Fabian Research Bureau and the Society for Socialist Inquiry and Propaganda (which in October 1932 merged with the pro-Labour rump of the old ILP to form the left-wing Socialist League). There was much excitement over these developments in Oxford, where Cole’s admirers were encouraged to see themselves as the vanguard of Labour’s intellectual revival.

The MacDonald and Snowden betrayal, and the subsequent Labour collapse, acted as the spur. ‘While the events of autumn 1931 lost thousands of voters to the Labour Party in the country as a whole’, recorded two young chroniclers of the University’s politics a couple of years later, ‘in Oxford the rapid growth of socialist opinion suffered no comparable set-back.’ By the end of 1932 the Labour Club had attained a record membership of almost five hundred, and a ‘Socialist Dons’ Luncheon Club’, with thirty or forty members, was meeting weekly.26 The upward curve of left-wing activity continued in 1933 and 1934, the year of Harold’s arrival at Jesus. As interest increased, however, so the orientation changed, away from the careful programme-building of Cole, and towards the international vistas and harsh dogmatism of King Street and Moscow.

Communism began to be important in Oxford in 1931, when some undergraduates set up the October Club, a Communist-front body whose secret aim was to control as much of Oxford left-wing politics as possible. Within a year, the Club had a membership of 300, which included many people who were also in the Labour Club. When Harold went up in 1934, the October Club was at the peak of its recruiting zeal: one of Harold’s first decisions on taking up residence was to reject the overtures of an Octobrist who wanted him to join, explaining politely but firmly (as Harold related in a letter to Marjorie), ‘I didn’t want to.’27 Many others, however, became members of both the October and the Labour Clubs, either gullibly or sympathizing with the Communist point of view.

When Harold went to his first meeting of the Labour Club, the ‘Marxist public school products’ were about to stage a Communist takeover. Anthony Blunt, the KGB spy, later described how Marxism ‘hit Cambridge’ (by which he meant smart, sophisticated Cambridge) early in 1934.28 It hit Oxford a few months later. An important development for Marxists in both universities, as for Communists generally, was an alteration in Moscow’s international tactics, occasioned by Soviet concern about a resurgent Germany. The switch was not sudden: rather, there was a gradual change of approach away from the former ‘Class against Class’ line to the ‘Popular Front’, officially adopted by the Comintern at its Seventh Congress in 1935. The new line meant that democratic socialists were no longer to be denounced as social fascists; instead they were to be coaxed into alliance in a ‘popular front’, or coalition of left-wing forces. This was the theory: in practice, it meant that Communists were supposed to use every wile to subvert Labour Party citadels. In Oxford it gave zealous Octobrists a motive for a fifth-column assault on the Labour Club, in the name of a ‘popular front’.

The merger between the two Clubs was brought about by secret Communists early in Harold’s undergraduate career. Christopher (now Lord) Mayhew, Harold’s exact Oxford contemporary and a Labour activist in the University, remembers that some two hundred Communist undergraduates ‘dominated the fifteen hundred members of the Labour Club, using techniques that are familiar enough today but frequently caught us off our guard then’. It emerged that, for some time, Labour Club elections had been rigged by the simple expedient of conducting a ballot and then falsifying the results.29 Philip Toynbee – who made his name as a public school runaway before going up to Oxford and becoming Communist President of the Union – later boasted that every member of the Labour Club executive was a secret member of the Communist Party, except Mayhew who ‘never seemed to have grasped that all the others were’.30 Mayhew’s own claim is that, though duped for a time, he eventually saw through the ploy.31 Later, Mayhew led a breakaway Democratic Socialist Group – anticipating the Social Democrat split in the national Labour Party half a century later, in which some of the same people were involved, taking the same sides. Mayhew himself was the first Labour MP to cross over to the Liberals, while the leader of the 1981 Gang of Four, Roy Jenkins, had also been an Oxford Democratic Socialist. Denis Healey, on the other hand, stayed with Labour in 1981 as he had done in the late 1930s when, although a Communist, he had been elected Chairman of the Labour Club.

It was fun to be a Communist at Oxford in the 1930s, if you had the money and the leisure to sustain the lifestyle. Toynbee claimed that when membership of the Party reached its peak in 1937 of 200 or so (eighty per cent of whom were undercover members, passing for ordinary supporters of other parties) it was far from being a public school preserve: at least half its membership came from grammar schools.32 This was not, however, the more vociferous half, and there was some justice in the comment of a critic in Isis, the undergraduate magazine, who wrote after a notable Union debate that if the Communists wanted to take power, ‘they really should insist that everyone is sent to a public school’. Oxford socialism had become an exclusive society with its own code and rituals. Labour Club members called each other ‘comrade’, not just in meetings, but also in private conversation. Isis noted that any serious office-hunter at the Union had to denounce capitalism. A socialist who wore the customary evening dress for debates needed to ensure that his bowtie was a ready-made one, ‘to show his contempt for bourgeois prejudices’.33

Philip Toynbee, who viewed bourgeois prejudices with a mixture of aristocratic and Marxist disdain, was the symbolic leader of this kind of gay and abandoned politics, which was designed to outrage headmasters, dons, old-fashioned fathers and Times leader writers and, incidentally, to spice up the social whirl. Toynbee’s nostalgic boast in later years was that ‘you bought silk pyjamas from your tailor in the High Street, danced the night away, and then shot off to CP headquarters for your secret instructions.’34 There was also an aphrodisiac quality: ideas about socialism and free love often mingled. Jessica Mitford (a left-wing Toynbee cousin) has given the best account of how, for the naughty children of the upper classes, sex, intellectual snobbery and demi-monde politics could come deliciously together.35 Toynbee’s own diary entries for the 1930s reveal ‘a dizzying mélange of Communist Party activities interspersed with deb dances, drunken episodes, and night-long discussions with fellow Oxford intellectuals – Isaiah Berlin, Frank Pakenham, Maurice Bowra, Roy Harrod’.36

At Cambridge, where Communism was similarly chic, not all its adherents were so frivolous: some, indeed, took it with a deadly seriousness. At Oxford the form the political fashion took depended critically on which year you happened to go up. Denis Healey, who entered Balliol in 1936, was recruited to the Communist Party the following summer by the poet Peter Hewitt, a friend of Toynbee’s. Though by now the doctrine was sweeping through political Oxford like an epidemic, its character was already changing. According to Healey, there was a key dividing line between undergraduates of his year, and those who started in 1935. ‘Peter and Philip … belonged to a different generation of Communists from me,’ he observes. ‘They had joined the “October Club” a year or two earlier, when Communists were very sectarian, got drunk, wore beards, and did not worry about their examinations.’ Following the 1935 change of Comintern line, however, a new earnestness took over: ‘Communists started shaving, tried to avoid being drunk in public, worked for first class degrees, and played down their Marxism–Leninism.’37

If there were aspects of the post-1935 approach which Harold might have found congenial, had he gone up in 1936, there was nothing in the pre-1935 style to appeal to him. Communists and fellow-travellers were to be found in the posh, arrogant colleges, like Balliol and Christ Church, not in modest establishments like Jesus: Steel recalls only one leading member of the October Club among his college contemporaries. There was nothing in common between the Toynbee circle and the Wilson circle, if it could be called a circle. ‘We were very naïve and innocent,’ says a Wilson friend. ‘For example, I don’t think I had ever heard of homosexuals when I was an undergraduate, and Harold may not have either. I had no idea that spies were recruited at Oxford.’ Instead of sex and popular fronts, Harold talked about Gladys, the Wirral, and his work.38 Others who came from a similar, grammar school or minor public school background, experienced Oxford political and intellectual friendships as a social elevator: chameleon-like, they adapted. Harold – and it was a disadvantage later on, as well as a strength – seemed to resist such influences. Unlike Healey and Jenkins, he never learned to sound like an Oxford man, and did not try. He did not mix with people from a different milieu. He stuck to his own. It was not that he disliked the Pakenhams, Crossmans and Gordon Walkers, young dons who helped to set the social tone as well as the socialist one, or even the Bowras, Berlins and Harrods. It was just that he never encountered them, except when he attended their lectures.

Harold did not shut himself off from politics altogether. He remained Labour-inclined for his first few months, toying with the idea of taking a more active part after the exam in December was over. At the end of the Michaelmas Term he had not yet despaired of the Labour Club: indeed, he must have participated to a certain extent because somebody nominated him as college secretary. He thought about it. One factor to be weighed in the balance was that Cole was President of the Club, ‘and all the coll. sees meet him a lot’. After the Christmas vacation, however, he decided not to accept the post, and to give up attending Labour Club meetings. The reasons, he told his parents cryptically, were ‘(a) LI. George (b) the Labour Party (c) am much more interested in foreign affairs than labour polities’. It was a clinching factor that meetings of the Labour Club clashed with a course of lectures on post-war Germany by the young New College don, Richard Crossman, which he was keen to attend. ‘These will be much more use than going to Lab. Club Friday evening meetings,’ Harold wrote to his parents.39

In his second term, Harold started going to the Liberal Club instead, and found it more congenial. ‘I went to the Liberal Club dinner: it was really fine – Herbert Samuel,’ Wilson wrote home in March, adding ‘I’m getting a few new members.’ He also began to attend meetings of a Liberal discussion group.40 Liberal activity, however, never absorbed a great deal of his time or attention, and always took third place to work and athletics. ‘Involvement in politics was somewhat peripheral in those days,’ recalls Sharpe.41 The Liberal Club is barely mentioned in Harold’s letters home after the Hilary Term of 1935, and seems to have ranked no higher than other societies in which he took a sporadic interest, like the League of Nations Union. Steel remembers only that Harold ‘went out and about and went to political meetings’ if there was an interesting speaker.42 Study was his preoccupation: none of his Oxford friends saw him as a politician, or even a potential one. Nevertheless, Harold’s participation in Oxford Liberal politics – limited as it undoubtedly was – contains a small mystery. It does not fit into a picture of a single-minded determination to succeed.

In a brilliantly argued polemic against Wilson, published in 1968 just as Marxism was once again in vogue, partly in response to the Labour Government headed by Wilson, the writer and journalist Paul Foot drew attention to early Liberal influences on the future Prime Minister that were supposedly formative. Foot also contrasted what he saw as the idealism of his own uncle, Michael Foot, who abandoned the Liberal Party to join Labour because he wanted to abolish capitalism, with the alleged complacency of Wilson, whose failure to make such a switch indicated that he had no such mission.43 A more obvious difference between the two politicians, however, is that Michael Foot’s party had some chance of eventually coming back to power, whereas Wilson’s had none. In the mid-1930s the Labour Party looked a pretty dismal prospect, but the Liberals – despite the continued prominence of one or two individuals, like Lloyd George and Herbert Samuel – seemed to be set on a path to extinction.

When Wilson joined the Oxford Club, it was at the nadir of its fortunes. What was happening to the Liberals nationally had been replicated, on a small scale, in the university. The Oxford Club’s membership was low, and it was in debt. If Harold still wanted to be an MP, let alone a minister, joining the Liberals was scarcely a stepping-stone. The puzzle about his choice is that he should have decided, for the time being at least, to place himself on the margin.

Even if he was intending to put his political plans on ice until he was professionally established – this is Mary’s suggestion44 – it was surprising, on the face of it, that he should have joined the one political party which offered the smallest future opportunity. Rather than a declaration of faith, or the first move in a political chess game, Harold’s decision looks like the casual act of an eighteen-year-old whose mind was principally on other things. However, few of Wilson’s other decisions were ever casual; and it is possible that this one was made, not in spite of the Liberals’ weakness, but partly because of it. What the fading Liberals offered Harold was a chance to show his mettle. There was little opportunity for him in the raucous Labour Club. The Liberals, on the other hand, gave him a leadership position almost at once. He had scarcely paid his subscription as a new member before anxious Liberal Executive members were asking him to become Treasurer. He accepted the office, took it seriously, and immediately began, with some success, to eliminate the Club’s deficit.

For the whole of his undergraduate career, Harold continued to take a benign and intermittently active interest in the Liberals. In his first year, he was even co-opted by a national Liberal Party group called the Eighty Club, which – somewhat pretentiously – regarded itself as having an ‘élite’ membership. Paul Foot regards this as evidence of a deep Liberal commitment. It may, however, have indicated nothing more than that an atrophying London dining and discussion society was seeking, by recruiting Oxford’s current officers, to replenish its ageing stock.

Wilson was a reasonably energetic participant in his first two years. During vacations he twice attended national conferences of the Union of University Liberal Students when these were held in the North-West. The first was in Liverpool after his second term, the second in Manchester after his fourth. At the latter, he spoke in support of the League of Nations, and his remarks were reported in the Manchester Guardian.45 His interest in that great newspaper, then based in Manchester and proudly Liberal in persuasion, may provide a partial explanation for his interest in Liberalism. Robert Steel recalls several occasions when he met Harold in the main quad at Jesus after dinner, and strolled with him to the Post Office in St Aldate’s in time to catch the midnight post: Harold was sending off his reports of Liberal Club meetings to the Manchester Guardian, effectively acting as a stringer.46 Later, as we shall see, Harold toyed with the idea of a career in journalism with the same paper. Liberal Party activity may have seemed a relevant qualification.

In Oxford Wilson’s main contribution was bureaucratic rather than political. Honor Balfour, a Liberal Club President and contemporary, recalled that Wilson ‘never took any initiatives or decisions’, but was good at recruiting members and collecting subscriptions. Frank Byers (later a Liberal MP and peer) remembered him for his efficiency as Treasurer, but not for any strong political line. This negative recollection was shared by another Club President, Raymond Walton: ‘I don’t remember ever hearing him propose anything political of any kind.’ Quizzed by Paul Foot, R. B. MacCallum, Wilson’s politics tutor, recalled only that he ‘could have told that he was not a Tory. That is all.’47 Such political blandness does not, indeed, support Foot’s own assertion of a Liberal indoctrination, or that Wilson was acquiring a stock of ineradicably Liberal ideas. We may take with a pinch of salt Wilson’s subsequent claim that in joining the Liberals he hoped ‘to convert them to my ideas of radical socialism’.48 But the lack of a socialist commitment is not proof of an incurably Liberal one.

Wilson’s involvement petered out after his second year, and he never took any part on the wider University stage. He knew none of the Union luminaries of his day. Denis Healey, who claims to have known all the leading Liberals in 1936–7, never met Wilson. He had ‘no role’ in Oxford politics, Healey concludes.49 Christopher Mayhew did not hear Wilson’s name mentioned until the beginning of their third year, and then it was for academic, not political reasons.50 Surprisingly, in view of his journalistic interest, Wilson did not write for the Liberal Club’s magazine, Oxford Guardian, started in 1936. Mayhew, Crossman, Heath, Dingle Foot, Jo Grimond, Richard Shackleton, Niall MacDermot – members of different parties – all crop up in the gossip column of this journal. Wilson’s name never appears in the magazine at all, except on lists of committee members and college reps.51 By the time he took Finals, he was still technically a Liberal, but his affiliation had become a merely token one.

In December 1934 Wilson reported that he was ‘swotting hard’:52 his efforts were rewarded and he passed the end-of-term exam without difficulty. Before doing so, he raised with the college the possibility of switching degrees from history to the newly established ‘Modern Greats’ course, which G. D. H. Cole had pioneered and which was composed of papers in politics, philosophy and economics. Given his interest in politics and recent political history, it was a logical step. His imagination had also been engaged by problems in economics: in a pre-exam college test in the subject he had come top, with the maximum possible marks. Permission to change was therefore granted, but with the proviso that he had to offer an extra language. He therefore learnt enough German in the Christmas vacation to satisfy his tutor, and embarked on the cocktail of disciplines which was to provide the basis for his academic and political career.

He also began to study in earnest. His first term of concentrated hard work had been a dress rehearsal for a period of eighteen months’ intensive application which transformed him from a promising, but not exceptional, eighteen-year-old into the outstanding student of his generation. How and why this happened is a second mystery. There was a happy coincidence of events: his parents were now well settled in Bromborough, and taking a keen interest in his progress; he himself was adapting to Oxford, delighting in its rituals and routines, and in a college whose social atmosphere suited him perfectly; and there was the challenge of a new degree in subjects that intrigued him. Yet these factors do not, in themselves, fully explain the driving will that seemed to be behind his almost fanatical attitude to study.53

Eric Sharpe, the future Baptist minister who occupied the room below Harold in 1934–5, suggests that Harold’s habits ‘reflected the protestant work ethic that characterized the atmosphere in which he had been brought up’.54 Other students shared the ethic, however, without the same results; and there was a Stakhanovite quality to Harold’s efforts which puzzled his contemporaries. His letters frequently describe the number of hours spent at his desk, as though these were an achievement in themselves. ‘I worked very hard last week,’ he wrote, typically, in March 1935; ‘touched 10½ hours one day, & 8 on several days – total – 46 hours for the week.’55 Even Harold’s own very diligent friends wondered whether ‘he led an over-regulated life, as if he feared that any minute departure from his highly disciplined routine would knock him completely out of gear.’56 Work became a kind of compulsion, of which he was never able to rid himself. Many years later he told an interviewer, revealingly, that he had ‘always been driven by a feeling that there is something to be done and I really ought to be doing it … Even now I feel myself saying that if I spend an evening enjoying myself, I shall work better next day, which is only a kind of inversion of the old feeling of guilt.’57 Possibly the knowledge of his parents’ sacrifice and hopes provided an incentive. Sharpe believes that ‘he felt he owed it to his family to be a success.’58 A later friend points a finger, specifically, at his father: ‘He had to do well because of Herbert. Harold knew he had to live up to expectations. Herbert put it all on him to fulfil his own ambitions.’59 Whatever the reason, Harold began to work with a ferocious determination that made him suddenly aware of what he might achieve.

He was a competitive, pragmatic worker, rather than an inquirer. He enjoyed the books he read, and his letters home show occasional bursts of intellectual enthusiasm. In May 1935 he described as the ‘finest book on the nineteenth century I’ve ever seen a study which he had just finished ‘all about the cross-currents of public opinion, & their effects on free trade, socialism, collectivism, factory legislation, communications, the Manchester School, etc.’ He added: ‘Dad would enjoy it.’60 Such comments, however, are less common than details about essays, marks and the flattering comments of tutors. A particular influence was his philosophy tutor, T. M. Knox, who noted his talent and encouraged him. There were only a couple of other Modern Greats undergraduates in Harold’s year at Jesus, so he was sent to other colleges for most of his economics teaching: Maurice Allen, the economic theorist, at Balliol, and R. F. Bretherton at Wadham.

Harold was not the sort of undergraduate who was taken up by the grander dons, and he was diffident, at first, about making himself known to them. It was not in his nature, however, to be anonymous, and he began tentatively to push himself forward. In the summer term, he was delighted when, after asking a question at the end of a lecture by the international affairs expert, Professor Alfred Zimmern, he was invited round by the lecturer to his house. ‘We discussed politics, international affairs, economics, armaments + everything,’ Harold told his parents. ‘In the course of conversation I asked him what was the best English newspaper on politics generally, + international affairs in particular: he answered immediately “The Manchester Guardian & not only in England but in the world …” & Zimmern is supposed to be the greatest living authority on International Affairs.’61

Meanwhile, Harold began to attend, and greatly to enjoy, academic discussion classes with G. D. H. Cole. He was one of eight or ten undergraduates taught together in this way, sitting on sofas and armchairs in Cole’s room and encouraged to smoke, which gave the occasions an atmosphere of relaxed sophistication. ‘It’s rather good to put questions to a man like him,’ wrote Harold. ‘On one of his bookshelves is a complete series of his publications – “Intelligent Man’s Guide to” etc. etc. It’s fine to look at them & listen to the author spouting.’62 In another letter, Harold wrote about having ‘some good fun’ with Cole. ‘He talks for five minutes then stops & asks “are there any questions?” I questioned him yesterday about one of his definitions which I thought implied a contradiction … he was decent enough to admit it … He’s a very nice chap!’63

Most of the undergraduates known to Harold were, like him, Nonconformist and Northern. Steel remembers him as one of a group of Jesus undergraduates from the North-West – especially from schools like Liverpool College and Liverpool Institute – who went round together. Eric Sharpe, the Baptist, had a Merseyside background, and so fits into this category. Arthur Brown, a near contemporary from another college who met Wilson at an economics seminar, had been at Bradford Grammar School. ‘It was our Northern-ness that caused us to take to each other,’ he thinks. ‘We had various places in common, the Wirral, Huddersfield and so on.’64 Steel had another link with Harold, through Gladys: both her father and his were Congregationalist ministers and, by coincidence, the Reverend Steel had succeeded the Reverend Baldwin as minister at Fulbourn.65

Though he had like-minded friends, he was not part of a set, and he lacked intimates. Sharpe, also at Jesus, thinks that ‘he did not make many close friends in college;’66 significantly Brown, who knew him outside college, assumes that Jesus was where most of his friends were to be found. He was often to be seen on his own, but imperturbably so; for Harold, social intercourse was an extra which, if need be, he could do without. Work was his favourite companion. ‘I am not wasting time going to see people and messing about in their rooms’, he wrote after an episode of particularly fierce endeavour in his third term, ‘for this is more interesting.’67 Some found him ‘in matters of personal sentiment’ to be reticent. But, though he frequently withdrew into his room for work reasons, he did not shun company. On the contrary, those who knew him speak of his openness, and describe him as gregarious and chatty. Brown’s picture is of a cheerful, self-contained young man, wrapped up in his work, yet with a sense of fun and an inveterate talker. ‘Harold was never at a loss for something to say,’ he recalls.68 Steel thinks of him as an extrovert, ‘who always had things to talk about and talked at considerable length’.69

Honor Balfour (who knew him in the Liberal Club) remembered him as ‘a trifle pompous – he talked and acted beyond his years’.70 Others give almost the opposite impression, and describe a chirpy, bouncy, overgrown schoolboy. Everybody agrees that he was an irrepressible show-off. He liked to boast about his academic and athletic successes; and to demonstrate his superior knowledge of most topics under discussion. Like his father, he also had a favourite party trick, which later became his trade mark. He enjoyed displaying his talent for recalling tiny details about trivial past events of the kind most people instantly forget. ‘He could remember things like the day he bought his pair of trousers,’ says Brown.71 He was an entertaining teller of stories, sometimes long ones. ‘You always knew he could embellish a tale in an amusing way,’ Steel remembers. He was universally considered – this was an unchanging feature, throughout his life – good-natured, without malice, and generous. Steel recalls that, as a graduate student, Harold was the proud possessor of a second-hand Austin 7 motor car. This he lent freely to friends. ‘Let me know if you want to borrow it again,’ Harold would say. So Steel got into the habit of letting him know, and passed his driving test in it.72

At the end of his first academic year, with Schools (Oxford’s final exams) not yet on the horizon, he set his sights on winning University prizes. Thomas, his room-mate, decided to put in for the Stanhope Historical Essay Prize; Harold had a shot at the Cecil Peace Prize, submitting an essay on the private manufacture of armaments, a set topic. He was unsuccessful. Before he had received this result, however, his tutors had encouraged him to consider competing for another accolade. ‘I’m definitely supposed to be going in for the Gladstone’, he wrote home in May 1936, ‘– and have been reading up some railway history.’73 His target was the Gladstone Memorial Prize, worth £100. He started to prepare a long, carefully researched and annotated paper on ‘The State and Railways 1823–63’. This combined several areas of interest: nineteenth-century politics, economics, and the Seddon family industry. The project took nearly two terms to complete, and eclipsed almost every other non-work activity. In the end, even running took second place.

He was content. More than that, he was happy – and never happier than when he was alone with his books. Helping to sustain his happiness, meanwhile – and enabling him to ignore Oxford’s many distractions – was the girl he had met at the Brotherton’s tennis club. After their first meetings, Harold had written to Gladys from Boy Scout camp. Then he had disappeared to Oxford, while she had remained at her office stool. But they kept in touch. ‘When Harold went up to Oxford we wrote to each other constantly,’ she recalls.74 Their letters to each other were not kept. Gladys, however, figures in almost every letter from Harold to his parents. He seldom used her Christian name, as if to do so would be over-familiar – even embarrassing, giving away too much about himself. He stuck to her initials. But she was nearly always there. He had a consistent purpose: to get his mother and father to see as much of Gladys Baldwin as possible, and bring her to Oxford whenever they could.

Since going up, Harold had one important thing in common with Gladys: both of them were living away from home. She, too, frequently felt lonely. ‘How’s G.B. going on?’ became Harold’s familiar refrain.75 Fond thoughts about ‘G.B.’ and nostalgia for the Wilson family hearth were closely linked. He tried to make light of things. ‘Do you ever see G.M.B. (Stanley’s niece)?’ he asked in an early letter. ‘How many walk her home from chapel? Why not give her a lift home some night? It will help to preserve the link. I believe she was going to the dance at Highfield last Thursday. Don’t forget about the lift home now & again; it’s a good idea. Let me know all the news about her as well as about everybody else.’ He added, almost mournfully: ‘I’m looking forward to Xmas, partly because the confounded exam will be over by then, but also because it will be nice to come home again.’76

Herbert and Ethel were obliging, happy to play the part of surrogate parents to their son’s girl, a role for which she was grateful. They had her round. ‘Got a letter from G.B. this a.m.,’ Harold wrote in February 1935. ‘She wasn’t ill, she’s been working very late. Evidently she was very fed-up last weekend – homesick, & that is why she went to see you. She said she felt a lot better after it … Her pa’s preaching at Chester. Are you going to ask them along for an evening?’77 A few days later, he wrote again: ‘Thanks for taking G B. out. I’m glad you did, because evidently she’d been feeling fed-up and homesick etc. the previous week. However she has the tennis dance on Mar. 2nd & her people are coming on the 9th so she should be OK now.’78 He did not let the matter rest. ‘Will you see the Baldwins next week?’ he urged at the beginning of March.79 His parents responded with an invitation.

On his nineteenth birthday, to Harold’s intense pleasure, Gladys sent him a pen-and-pencil set. It was mid-term: he could not go to the Wirral. He decided to engineer a family visit to Oxford. His room-mate, Thomas of Tenby, had recently been in hospital for an appendicectomy. Illness, it occurred to Harold, was something that made parents concerned about their offspring, and even wish to see them. He developed stomach pains. ‘I wish you could come up next weekend, if at all possible – it would make things a lot easier – esp. re my tummy,’ he wrote. ‘If you could come –’, he added with even greater ingenuity, ‘it would make it a lot easier to settle down & work for the rest of the term … please come next weekend if at all possible (& bring G.B.). Remember me to G.B. if you see her at tennis, or anywhere – she probably won’t be down to tennis much as it’s her overtime etc. this week.’80 The ploy was successful: the visit took place, the first of several with Gladys in the car, generally after some campaigning by Harold. Whenever his parents planned a trip to Oxford, Harold asked if they could bring ‘G.B.’

‘Hope G.B.’s getting on OK, thanks for “looking after her” last week,’ Harold wrote in May, beating a by now familiar drum. ‘And will you also please pay my tennis club subscription this week, so that I’m on the list of members in good time.’81 It was a joyous summer, back in the Wirral, with Gladys, the Brotherton’s club, and tales of Varsity life to tell. There was also a twinkle of ambition. That October, Harold returned to Oxford for his second year, refreshed, and with his eyes fixed on an immediate goal. He went to lectures and visited the Iffley track. He also read up about railway history. When running fixtures ceased in November, he threw himself into his research. ‘I haven’t any news as I’m spending all my time on the Gladstone just at present,’ he wrote.

Harold barely noticed the general election on 14 November, at which Labour – led by a hitherto obscure MP called Clement Attlee – staged a modest recovery. He joined fellow undergraduates at the Oxford Union, to hear the results read out as telegrams came through. His interest in them, however, was largely parochial. ‘Fancy that wet Marklew getting in, and that hopeless Mabane’, he wrote, ‘– but he only had Pickles of Crow Lane School against him.’ Ernest Marklew was a Grimsby fish merchant, who won the Colne Valley division for Labour; W. Mabane was the sitting Liberal National MP for Huddersfield. Harold was pleased by the victory in one of the Oxford University seats of the author and barrister A. P. Herbert, standing as an Independent, who defeated a man called Cruttwell: ‘very unpopular – a snob’, wrote Wilson. In his current, Oxford-enhanced, scale of values, social snobbery was one of the worst sins.82 That the Liberals lost ground badly does not seem to have bothered him greatly.

During the Christmas vacation he continued his researches at the Picton Library in Liverpool, consulting Government Blue Books and volumes of Hansard, for parliamentary debates. Back in Oxford, he did not let up. ‘The Gladstone is dragging on: I’m more or less in sight of the end of it,’ he wrote at the end of January.83 His attention was diverted by the triumph of one of his lecturers. ‘Have you heard about Crossman?’ he asked his parents rhetorically – it was unlikely that they had. ‘At New College the Sub-Wardenship circulates among the fellows, & this year it is Crossman’s turn. As H. A. L. Fisher (Warden) is off for six months, Crossman (aged 26) is acting warden for the year!!!’84 It was difficult to imagine a more dizzying achievement. Compared with this, Harold’s own efforts seemed mundane: but he pressed on. Early in March he handed in his paper, which he had paid to have professionally typed. ‘Into the unsettled England of the eighteen twenties the locomotive burst its way,’ it began, ‘heralding the new industrial order of which it was to form so important a part.’ While he waited anxiously for the result, he speculated about the length of his bibliography, and about tales of previous, streetwise, contestants who had hoodwinked the assessors by listing large numbers of books they hadn’t read.85

There were not many entries, and the verdict was quickly reached. A small item in The Times on 18 March announced: ‘The judges have reported to the Vice-Chancellor that they have awarded the Gladstone Memorial Prize, 1936, to J. H. Wilson, Exhibitioner of Jesus College.’ It was a moment, as important as getting an award at Jesus, when the world changed. The Gladstone Prize was his first public distinction, a major one in Oxford, marking him out from his contemporaries not just in Jesus but in the University. Harold’s pleasure was unbounded, and so was Herbert’s, as the letters of congratulation arrived, including several from the Colne Valley and Huddersfield. Harold, in his joy, wrote to Helen Whelan, the class teacher who had taken an interest in him at Royds. She was deeply moved. ‘What a far cry from “James Harold” who protested vigorously against the “James”, to Mr Wilson winner of the Gladstone,’ she replied, affectionately and teasingly. ‘And yet in writing to say thank you for a singularly charming letter, I feel that I am almost more pleased to renew a friendship that has many happy memories than to tell my former monitor with what very real pleasure I read of his triumph … I should like to see you so much I feel tempted to appear in Oxford when your less elderly lady friends are not besieging you for tea.’86 Ethel and Herbert motored down from the Wirral to hear Harold give the Prize Oration in the Sheldonian Theatre. Gladys came too, the admiring girlfriend, the only lady friend that mattered. ‘I felt very proud of him,’ she remembers.87

In Oxford, people who had barely noticed Harold, now began to do so: from being a run-of-the-mill undergraduate from an inferior college, he became a man with possibilities. Cole asked him to give a paper to his discussion class, and complimented him generously afterwards. Harold glowed. ‘Cole says he agrees with it completely & is using some of my figures – which I left with him – to produce at the Econ. Advisory Council (of the Prime Minister)’, he wrote home in May, ‘as a very strong section of that (and also “The Times”) are in favour of the Macmillan Report suggestion which I attacked from start to finish, basing my attack on facts not prejudice’.88 He also gave a paper to the Jesus College Historical Society on ‘The Transport Revolution of the Nineteenth Century’, based on his study, which – according to the college magazine – added ‘a quite unheralded glamour to the economic problems of the day’.89 He had been elected Secretary of the Sankey Society, the college debating club, the previous December. In June, Lord Sankey himself, just retired as Lord Chancellor, and himself a Jesus man, attended the Society’s dinner as guest of honour, sat next to the Gladstone Prizeman and talked to him at length. When a fellow member of the Society told him about Wilson’s success, Lord Sankey warmly grasped Wilson by the hand, ‘& said he remembered the result, & had a good breakfast that morning. He says he always does when a Jesus man gets anything’.90

Having acquired the taste for academic honours, Harold indulged it. At the beginning of his third year, he sat the competitive exam for the George Webb Medley Junior Economics Scholarship, worth £100 per annum, and won that too – giving him financial independence of his father. It was not an unexpected success: the Gladstone had already made his name in the University as an academic force to be reckoned with. Christopher Mayhew, elected President of the Union the same term, also entered for the Webb Medley. ‘You’re a bit optimistic,’ said a friend. ‘Don’t you know that Wilson of Jesus is in for it?’91

A key event in the fast-changing discipline of economics occurred in the second term of Harold’s second year, before he sat for the Webb Medley. The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money by J. M. Keynes was published on 4 February 1936. Its appearance had long been heralded, and economists approached the publication date with excitement. Arthur Brown, already a Keynes enthusiast, went to Blackwell’s bookshop in Oxford and bought a copy the same day.92 Harold was also interested, though his response was more muted. He had yet to hear the Gladstone result, and he was short of cash; so he cast round for a benefactor. Fortunately, his twentieth birthday was coming up. At the beginning of March, he wrote home with instructions for Marjorie to buy him ‘J. M. Keynes’s bolt from the (light) blue’. It was a book, he explained, that he had to read, though he added ‘[an] Oxford don said to me that Keynes had no right to condemn the classical theory till he’d read a bit of it.’93

Wilson records in his memoirs that he read The General Theory before taking his final examination in 1937 94 – a formidable undertaking for an undergraduate. Meanwhile, he had joined a select band of invited undergraduate members (who included Arthur Brown and Donald MacDougall, future director of the Department of Economic Affairs during Wilson’s premiership) of a research seminar on econometrics run by Redvers Opie and Jacob Marschak, where Keynes’s book was discussed. Wilson, however, was practical in his approach: The General Theory was not part of the syllabus, there had been no ‘Keynesian’ question in the 1936 exam papers, and at least one of the examiners for 1937 was known to be an anti-Keynesian. The new ideas, therefore, did not form part of the corpus of knowledge which he stuffed into his head.

Much was expected of him, and he was widely tipped as ‘the brightest prospect’ of his year for the PPE degree.95 ‘His industry can only compel admiration,’ wrote one of his tutors in a testimonial for a couple of academic posts (which he did not get) shortly before his Finals.96 His methods were largely mechanical, though spiced with cunning. Swotting for his philosophy paper, he made a digest of Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason, then made a digest of the digest, which he learnt by heart.97 The technique was remarkably effective. One of the examiners – his own economics tutor, Maurice Allen – maintained afterwards that although Wilson’s papers showed diligence, they lacked originality. They also indicated that the candidate had studied the dons who were going to mark his scripts, and played to their prejudices.98 Such a comment, however, was a grudging one, in view of Wilson’s performance. He obtained an outstanding First Class degree, with alphas on every paper. As Lord Longford (then Pakenham and himself a don) later observed, no prime minister since Wilson’s fellow Huddersfieldian, H. H. Asquith, had ever been able to boast such a good result in Schools.99