Читать книгу Harold Wilson - Peter Hennessy, Ben Pimlott - Страница 17

Оглавление9

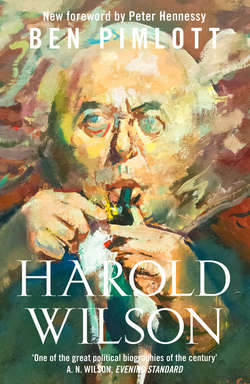

NYE’S LITTLE DOG

The general election preserved the Government, but also effectively immobilized it. In some ways, indeed, Labour’s position in the new Parliament was even more precarious than in 1929 because of the absence of an adequate number of Liberal or other non-major party MPs to act as a cushion on whipped votes. For the next twenty months the Government stood in constant danger of sudden defeat, and of a new contest at a moment not of its own choosing. There was a sense of transition, even of interregnum: of old men moving on, and new men seeking their places. Cripps and Bevin, both terminally ill, soon left politics; other leaders had lost their élan. ‘Austerity’ remained, but the dire emergency had passed, and with it any easy justification for socialist planning. Because of the parliamentary tightrope, the Government’s agenda was largely restricted to noncontroversial legislation. Meanwhile, political attention shifted away from domestic to foreign affairs, and to a developing conflict in the Far East. Fear of a Third World War, which began even before the Second War had ended, had never been more intense.

On the home front, pre-war socialist aims had either been achieved or abandoned. What remained was a broad acceptance of a theory which, though harnessed to socialist beliefs, had little to do with Labour Movement rhetoric. A Fabian–Keynesian amalgam, anticipated by Douglas Jay before the war, was now close to an orthodoxy not just among politicians but among many of their advisers as well. Although there were some differences of emphasis, until the summer of 1949 and the debate over devaluation, there had been few areas of major disagreement between ministers and civil servants on economic policy. Attlee’s choice of former wartime temporary civil servants for key political posts was one reason for this. Here was a tight and homogeneous world, in which officials and politicians – who owed their power to a political organization largely oblivious of its existence – conducted their arguments in a private language with others of their own kind.

But the consensus was a pretty fragile one. Harmony among economic ministers had been maintained by the powerful leadership of Sir Stafford Cripps, whose intellect and zeal were an inspiration to junior and satellite ministers, as to officials. The devaluation crisis and its bitter aftermath ended the era, and provided the ingredients of strife. Even if Cripps had remained physically robust, his authority would still have been challenged. Growing evidence of his frailty created an atmosphere of uncertainty and anxiety, exacerbating policy differences.

As we have seen, both Wilson and Bevan had suggested a splitting of the Chancellor’s responsibilities, partly as a way of reducing the burden on Cripps. By the beginning of 1950, Dalton supported this argument – and he also had a candidate for the new post, if it was created. At the end of January he had a significant conversation with the Prime Minister about the disposition of economic posts, should Labour stave off defeat in the election. Cripps was irreplaceable as Chancellor, Dalton told Attlee. No one else could do the work, ‘until, in due course, one came down the line to the “young economists’”. However, Cripps had too much to do, and a Minister of State was needed to help him:

I thought Gaitskell was the man for this job. He agreed. Generally, he said he was already discussing this with Bridges. But the new minister must have a defined sphere of responsibility – mainly perhaps in the ‘old Treasury’ field. We agreed that Gaitskell was better for this than Wilson (though he was doing very well), or Jay, who, though very able, had not always good judgement, and wasn’t very personable.

Dalton went on to recommend that, in due course, Gaitskell ‘probably should be Chancellor of the Exchequer’.1

Events turned out much as Dalton had proposed. After the election, Gaitskell was appointed Minister of State at the Treasury. Wilson remained at the Board of Trade. His reaction to Gaitskell’s appointment is not known. It is unlikely, however, that it was one of pleasure.

There were only two Board of Trade measures of importance in the new Parliament – a Distribution of Industry Bill, and the establishment of the National Film Finance Corporation, both of which were welcomed by the Opposition.2 Wilson remained much preoccupied with films. In November, before the election, he had flown to New York to attend the FAC Conference, meeting the Hollywood administrator, Eric Johnson, while he was there.3 There was growing pressure to ease restrictions on imported American films. Wilson continued to take a close personal interest in the problem. In May, during Anglo–American talks on the film industry in London, he gained a good deal of attention in the popular press, which was interested in the link with the world of show business. Meanwhile, his role as minister of rationing and red tape made him a butt of the decontrolling Opposition’s guerrilla warfare.

Dollar-earning continued to be his main preoccupation as President. In May he called for better productivity, new designs and new products, to beat the fast-moving Germans and Japanese.4 In June he announced that the production of nylon stockings was six times what it had been eighteen months earlier, and was now the equivalent of a pair a year for every woman in Britain.5 In July, following the discussion by colleagues of his paper, ‘The State and Private Industry’, he expounded the new doctrine of the mixed economy. Free enterprise plus planning equalled freedom, he declared. This simple equation constituted ‘a living and virile faith which alone will fight the menace of Communism’.6 In September, he announced a rapidly increasing output of cars and a booming, dollar-catching tourist trade.7

But the Board’s production-and-export campaign could not insulate the economy against world events. In June, a crisis in Asia suddenly transformed the economic outlook: the North Korean Communist invasion of the South brought an immediate British promise of military assistance to the Southern army. In August, the Cabinet agreed a greatly increased defence programme, with only Aneurin Bevan voicing his dissent. Though in the Cabinet majority, Wilson was more aware than most ministers of the implications at home. Production targets had to be revised, and he had to deny rumours of a possible extension of rationing.8

The direction of economic and financial policy remained uncertain because of the health of the Chancellor. This uncertainty was about to be resolved. As in 1949, Sir Stafford Cripps took a long summer break from his duties. This time he left one minister, not three, to deputize for him. There was no doubt about who that minister should be: Hugh Gaitskell, the recently appointed Minister of State. The temporary arrangement soon became permanent. In October, Cripps resigned and Gaitskell, increasingly authoritative as ‘Vice-Chancellor of the Exchequer’, succeeded to his office, the appointment taking effect on 19 October.

It caused little surprise. Gaitskell was already in charge. He was technically equipped for the job and had a good reputation. Nevertheless there was resentment among older, better established leaders who regarded the recently elected new Chancellor as an upstart. Emanuel Shinwell was piqued at the rapid promotion of a minister who had already displaced him at Fuel and Power. Aneurin Bevan, who – as the successful head of a major department – had a claim himself, wrote the Prime Minister a furious letter of protest.9 Bevan’s reaction stemmed partly from a sense of humiliation at being passed over by a middle-class intellectual. But there was also a political aspect, of which the post-devaluation row had been a foretaste. Bevan took a sharply different view from Gaitskell about public expenditure and, in particular, the need to protect spending on the social services.10 Personal grievance now fuelled ideological anger, and for days the Health Minister complained bitterly to anybody who would give him a hearing.11

Did Wilson also feel bitter about Gaitskell’s appointment? Gaitskell believed so. In his hour of victory, the Chancellor recorded that ‘HW, and others confirm, is inordinately jealous.’12 Jay thought the same,13 and so did Pakenham.14 That such a theory was not just a scornful assumption is suggested by a close friend of Wilson who recalls him saying, many years later, that he had hoped Cripps would lay the ground for his own succession, and that ‘it was a blow when Hugh got it.’15 If that is correct, then – however disciplined Wilson might have been in other ways – he had allowed his appetite to get dangerously out of hand. For if Wilson had once seemed the obvious successor to Cripps, this had ceased to be the case. In May, Robert Hall of the Economic Section noted that Wilson’s stock was falling, and ‘he who was once thought to be the obvious next Chancellor, is not now so regarded.’16 Still, as Gaitskell triumphantly put it, ‘one does not look for reasons for jealousy.’17 Wilson could consider himself better qualified academically than Gaitskell, and was senior in rank to him in the Government. The Chancellorship had been his childhood fantasy. These were reasons enough.

In January 1951, Aneurin Bevan was moved from Health to Labour. This was a sideways step, rather than a promotion. He was reluctant to make the change. A few months later, he told Dalton that Attlee had double-crossed him. ‘I refused for some time,’ he said, ‘I only agreed when he promised there should be no cut in the Social Services.’18 Two months later, Ernest Bevin was shifted out of the Foreign Office because of his deteriorating health, and Morrison became Foreign Secretary: an appointment which added to Bevan’s frustration.

Yet there was more to Bevan’s gathering attack on the Government’s expenditure plans than bad temper. As we have seen, Bevan had backed his arguments with the threat of resignation long before any of the ministerial changes to which he objected had been made. Not only had he strongly disapproved of Cripps’s proposals for cuts in the social services following devaluation: in the winter of 1950–I he had opposed the drift into rearmament and into a greater defence commitment in the Far East. He had frequently argued that it was part of Soviet strategy to try to force Western countries to undermine their economies by spending money on arms, and so embitter their own peoples.19 By the time that Gaitskell announced his intention to levy charges on false teeth and optical services as part of a package of economies to finance the defence programme, it was well known that Bevan had deep objections to such a policy.20

It was less well known that the President of the Board of Trade shared them. Wilson had backed Bevan against Cripps in Cabinet over post-devaluation cuts. But he had taken no public stance, and he continued to be regarded as an orthodox member of the Cabinet.21 Indeed there is one piece of evidence which suggests that Wilson’s immediate reaction to Labour’s losses in the election was to blame the Left. Streat’s diary records a conversation just after the result, in which the President offered four explanations for the Government’s set-back. One was Bevan’s notorious ‘vermin’ speech (Bevan had caused an outcry by calling the Tory Party ‘lower than vermin’); the second was ‘a fear that the Labour Party would be driven by its left wing to nationalize for the sake of nationalization’. The others were housing and the cost of living, on which Wilson felt that the Conservatives had the best of the argument. Streat concluded, not unreasonably, that Wilson ‘must be taking up a position in the councils of the Labour Party in opposition to all that Nye Bevan stood for’.22

If, however, Wilson briefly toyed with the idea of attacking Bevan rather than supporting him, his position altered over the months that followed. By the beginning of 1951, he was firmly allied on spending issues with the newly appointed Minister of Labour. From the start of this controversy, the Chancellor doubted his sincerity.

Early in 1951 Cabinet accepted a programme of rearmament. Wilson was one of the principal opponents. Gaitskell believed that those who argued against did so ‘partly just as an alibi in case the programme could not be fulfilled or exports dropped catastrophically’. He identified a cleavage in the Government between ministers who recognized the Communist menace, and ‘anti-Americans’ who did not, some of whom were playing to party opinion. He considered Wilson the worst offender:

One cannot ignore the fact that in all this there are personal ambitions and rivalries at work. HW is clearly ganging up with the Minister of Labour, not that he cuts very much ice because one feels that he has no fundamental views of his own, but it is another voice. The others are very genuine.23

On 15 March the Chancellor advocated at the Health Service Cabinet Committee a limit to expenditure on health at the existing level of £382 million. He also recommended the imposition of a charge for false teeth and spectacles that was expected to raise £13 million (£23 million in a full year). At full Cabinet a week later, Bevan angrily denounced this proposal, declaring that if the Chancellor was not prepared to accept a tolerance of a few million in his budgeting, he should meet his difficulty by reducing defence expenditure. Wilson strongly backed him. ‘The President of the Board of Trade said that he found it difficult to take a final view of the Chancellor’s proposals without having full information about the Budget,’ the Cabinet minutes record. ‘He agreed with the Minister of Labour that a question of principle was involved and that a free National Health Service was a symbol of the Welfare State. If the proposal for charges was accepted, it would be widely said in the United States and elsewhere that this country had abandoned one of the main principles of the Welfare State. He thought there would be difficulty in spending the amounts allocated for defence in the next financial year because of raw material shortages and other shortages; and he would therefore have preferred to see a cut in defence expenditure rather than a scheme of charges under the National Health Service.’24

On 8 April the Minister of Labour returned to the attack. Reiterating his concern about the danger of rapid rearmament to the economies of Western democracies generally, Bevan threatened to resign if the charges were implemented. At a reconvened Cabinet meeting later the same day, Wilson told colleagues for the first time that if the Cabinet maintained their decision to introduce charges, ‘he would feel unable to share collective responsibility’ and would resign as well.25

Wilson later recalled trying to persuade Gaitskell, in a taxi, not to regard Cabinet as a battleground, but as a place for give-and-take.26 This was Wilsonism. It was not Gaitskellism: the Chancellor did not yield. On 9 April Wilson joined Bevan in warning Cabinet of the danger of back-bench abstentions – which could force an election – if there was a ‘departure from the principles of a free Health Service’.27 Next day Gaitskell announced the changes in his Budget speech. On 12 April, Herbert Morrison, chairing Cabinet in the absence of Attlee who was in hospital for a duodenal ulcer operation, ruled that the Health Services Bill could not be delayed. At Cabinet a week later, Bevan said that he could not vote for the Bill on the Second Reading. In hospital Attlee, kept informed of developments, described Bevan as a ‘green-eyed monster’, implying that jealousy was at the root of his rebellion.28 On 22 April Bevan resigned. Wilson followed him out of the Government on 23 April, together with John Freeman, a junior minister at Supply.

Why did Wilson resign? Public attention throughout the dispute focused on the Chancellor and on Aneurin Bevan. Politicians and journalists argued bitterly about the rights and wrongs of Bevan’s resignation. The political damage it caused to the Labour Party was attributed to him. Harold Wilson was barely noticed. Yet, of the two Cabinet resignations, Wilson’s remains the more intriguing.

The 1931 crisis apart (when the whole Cabinet offered its resignation after failing to agree to the Chancellor’s proposal for cuts in benefits), resignations from Labour governments had been rare. Before 1951, a total of four ministers had resigned because they refused to continue to accept collective responsibility: but of these only one was a Cabinet minister (Sir Charles Trevelyan in 1931) and only one other was of any prominence (Sir Oswald Mosley in 1930). A parallel between Mosley’s resignation and that of Bevan (who had considered following Mosley into the New Party) did not escape the notice of Cabinet veterans in 1951: both departures involved more than a simple disagreement, and both were presented as broad, passionate and ideological appeals to the Labour Movement. Wilson’s resignation, on the other hand, had no parallel. Unlike any of the other resigning ministers, including Bevan, Wilson had hitherto appeared a conventional politician of prosaic opinions, who made reasoned calculations, who preferred compromise to confrontation, and whose judgement had so far not failed him. He was not unstable or impulsive. None of this proves that his resignation was cynical. But it does leave us with the question of what he hoped to achieve.

It may certainly be argued, with the wisdom of hindsight, that Bevan and Wilson were right on the central issue and Gaitskell was wrong. ‘The Budget of April 1951 may fairly be considered a political and economic disaster, for all the immense talent of its author,’ the historian Kenneth O. Morgan has argued persuasively. It was particularly insensitive for a fledgling Chancellor, facing opposition from a senior colleague, to refuse to treat health service expenditure any differently from food subsidies.29 Denis Healey, who had little time for Wilson then or later, believes that Wilson had the better case on defence spending.30 Much of the enormous rearmament programme was never carried out, and the subsequent Conservative Government implicitly acknowledged Gaitskell’s error, Churchill admitting as Prime Minister that Bevan ‘happened to be right’.31 Wilson himself always insisted that he resigned on the rearmament programme, in the context of an over-stretched economy, not on the health charges (though the Cabinet minutes show that he stressed both). There was also a departmental concern: as President of the Board of Trade, Wilson had been made aware that military demands, at home and in the United States, were exacerbating shortages of sulphur and essential metals, such as nickel, tungsten and molybdenum.32 But to fight was one thing, to go another. Normally, as one former colleague puts it, ‘a minister who disagrees makes his views known, but stays.’33 What makes Wilson’s decision so odd is not the logic, in terms of policy, but the risks he was willing to take, and the damage he was prepared to inflict in order to defend it.

Behind the issue itself lay personalities and wider politics. In his memoirs, Wilson blames Gaitskell’s inflexibility on the one hand and strategic cunning on the other. According to Wilson, the Chancellor treated opponents as heretics, trouble-makers or fools, while at the same time nurturing an ambition eventually to seize the Leadership for himself, it was not long before that ambition took the form of determination to out-manoeuvre, indeed humiliate Aneurin Bevan,’ claims Wilson, ‘If he could defeat Nye in open conflict, he could be in a strong position to oust Morrison as the heir apparent to Clement Attlee.’34 This became the accepted view among Bevan’s friends, who saw the whole crisis as (in Peter Shore’s words) ‘an attempt to ease Bevan out, by creating a situation he could not accept’.35

Few of Bevan’s friends, however, believed that Wilson’s resignation was motivated solely by a desire to prevent this happening, or by the issues under dispute. They supported and applauded the gesture, while assuming that the underlying motive was self-interest. Normally a resignation jeopardizes, if it does not terminate, a political career. That is the puzzle. ‘He may have thought Nye represented the beating heart of the Labour Party’, suggests Tony Benn, elected in 1950, ‘that the Party under Herbert Morrison had lost its vision and would move to the Right.’36 Michael Foot believes that Wilson was ‘naturally attracted to Nye’.37 Most others – on Left and Right – take for granted that it was a move on the chessboard.

‘Wilson believed Bevan would become Leader, and that to make his own way he needed to court the Left, which was on the rise,’ says Woodrow Wyatt, who was moving in the opposite direction.’38 ‘Harold had discovered that the right wing didn’t trust him,’ maintains Harold Lever, ‘If he was to have muscle in the Labour Party, it would have to come from the Centre and Left.’39 Ian Mikardo ties the decision to the coming election, in April 1951, the Labour Government was getting more and more discredited,’ he argues. ‘Harold didn’t want to be associated with the run-down. He was deserting a sinking ship, and going with people he thought would compose the new leadership. He was leaving the dead bodies of people who were not going to be key elements in the next Labour Government.’40 Others point out that Wilson was well aware that, in the Labour Party, leaders had tended to come from left of centre.

A divergence over policy, which included a shrewd assessment of the likely impact of defence spending on the economy; a personal rift, in which jealousy may have played a part, coupled with frustration about Gaitskell’s style; fascination with Bevan, and appreciation of his potential, linked to a bitter determination, if possible, to block Gaitskell’s path: all were doubtless contained in the pot-pourri of reasons for backing the Minister of Labour. There may also have been another factor, little noticed at the time, but certainly a major preoccupation for Wilson. This was his growing anxiety about Huyton and the danger – which was beginning to look like a near certainty – that he would lose it in an election that could happen at any moment.

The selection of the twenty-five-year-old Anthony Wedgwood Benn to fight a by-election in Sir Stafford Cripps’s old seat, Bristol South-East, in November 1950 was a significant event, not just because of the youth of the candidate and the lustre of the man he was to replace. Wedgwood Benn won the nomination despite the inclusion on the short-list of Arthur Creech Jones, a respected former Colonial Secretary who had had the misfortune to lose his seat the previous February. Transport House had done its best to secure the Bristol South-East selection for Creech Jones, just as it had worked to get Cripps selected almost twenty years before. This time, however, there was a breath of rebellion in the constituency air. Since the end of the Second World War, constituency party membership had been expanding fast. Where, in the past, it had been possible for Tammany Hall tactics to hand selections to members of the hierarchy who had Transport House approval, it was becoming much less easy. Bristol South-East was a sharp reminder that a defeated minister, however important, could not automatically expect a ticket back.

The Bristol selection was of immediate interest to Wilson, because of the likelihood that, like the luckless Creech Jones, he would soon be looking for another berth. Unemployment stared him in the face. ‘Harold has to put in such a lot of time at Huyton to be sure of retaining the seat,’ Gladys told a friend. ‘He’s started a weekly “surgery” where he answers all the problems of the people – and if he can’t give an answer he jolly well makes sure that someone else does.’41 In January 1951, the Conservatives moved into a 13 per cent lead in the national opinion polls, rising to 15 per cent in March before easing slightly to 12 per cent in April. On 5 April, a by-election in neighbouring Ormskirk (Tory-held, on new boundaries) showed a 6.2 per cent swing against Labour. Just before the Budget crisis, it was noted in the press that Wilson’s prospects in Huyton, where there was a very active Tory challenger, looked gloomy.42 Once the prescription charges row broke, the issue of his own possible resignation, and his constituency prospects, became closely entangled.

The turning-point in the crisis had come on 3 April, when Bevan made a famous public outburst, telling a crowd in Bermondsey that he would never be a member of a government which made charges on the National Health Service for the patient. Next day Dalton, who supported some aspects of Bevan’s defence argument and tried to act as honest broker between the two sides, talked to Wilson at length. The President of the Board of Trade used the opportunity to tell Dalton that he ‘would have to consider his own position if Nye resigned’. According to Dalton’s diary account, Wilson also said that ‘he couldn’t hold Huyton and was thinking of moving.’ The Labour Party national agent, R. T. Windle, had advised him ‘to wait till the last moment’, presumably meaning the end of the Parliament, when any sudden vacancy had to be filled in a hurry, and consequently was easier to fix centrally. Dalton replied brutally that resigning ‘wouldn’t help him find a better ‘ole [i.e. a better bolt-hole] with the aid of Transport House’.

When Dalton said that the health charges issue was a very narrow one on which to resign, Wilson made a reply which indicated, not only how his own mind was working, but also how far ahead the rebels’ strategy had been planned. ‘He said it would soon be widened,’ Dalton wrote. ‘Nye, once out, would attack on Foreign Policy, etc. He was young enough to wait for power and leadership.’ Dalton, whose main loyalty was to Gaitskell, reacted to these calculations with despair and disgust. Formerly, he had seen Wilson as one of his ‘young men’, a protégé. No more. ‘Harold Wilson is not a great success,’ he noted angrily. ‘He is a weak and conceited minister. He has no public face. But he is said to be frantically ambitious and desperately jealous of Hugh Gaitskell, thinking that he should have been Chancellor. He has disappointed me a lot.’

Why – we may wonder – did Wilson mention both his plan to threaten resignation (which was not yet known to most colleagues) and his constituency anxiety and intentions to Dalton, of all people, who was known to be a close friend of Gaitskell? Possibly Wilson – understandably overwrought, and contemplating a major decision – simply blurted out his thoughts on two unrelated problems which were simultaneously concerning him. Alternatively, he had some sort of deal in mind. He may have been putting out a feeler. Dalton had often helped young friends find seats in the past. It is at any rate notable that Wilson should have told Dalton, who was famous for his indiscretions and was certain to tell Gaitskell; yet he did not inform his fellow dissenter, John Freeman. When Dalton spoke to Freeman a couple of days later, the junior minister was ‘very contemptuous of Harold Wilson, when I told him he was asking Windle to find him a last minute bolt hole from Huyton’.43

Whether or not the possibility of a tacit buy-off – a seat in return for staying in the Government – entered Wilson’s head, it certainly occurred to others, who were aware of his predicament. Wilson himself mentions in his memoirs that when Ernest Bevin died on 14 April, at the height of the dispute, the prospect of selection in Bevin’s seat, Woolwich East, ‘was used in a plot to lure me out of the Bevan camp’. He claims to have turned down such an offer.44 That such an idea was still being actively discussed until just before the resignations is indicated by a Daily Telegraph report on 25 April (after the ministers had left the Government). Almost on the eve of their departure, the resigners had apparently hesitated in the hope of a compromise in the health charges issue; and, moreover, ‘Mr Wilson had also received assurances that a safer seat than his present constituency … would be found for him.’

Both sides can signal, without meaning anything definite by it. Wilson may have believed that he was offered a bolt-hole: Hugh Dalton’s diary makes it plain that Dalton was working hard to make sure he did not get one. Two days before Bevin’s death, Dalton and Morrison decided between them that Wilson should be given no favours. ‘I rang up Windle this morning before Cabinet as agreed with Morrison’, Dalton recorded on 12 April, ‘and told him this was a joint message from Herbert and me – Harold Wilson must not be helped to find a better seat; if Huyton was to be lost, let him lose it! Windle said he wasn’t helping. I said Wilson had suggested to me that he was. Anyhow Windle took the point!’45 Such a combination of heavyweights was virtually insuperable, and we should assume – whatever may have happened earlier, or whatever may later have been leaked – that it now blocked off any short-term possibility. ‘Who dishes out safe seats in the Socialist Party?’ wrote John Junor in the Express on the day of Wilson’s resignation. ‘The man in control of the machine, Mr Herbert Morrison. And Mr Morrison’s hostility towards Bevan men must at this moment know no end.’

This was how the Tory press saw it, and it was still true up to a point. But what upsets like the Wedgwood Benn selection in Bristol showed was that Morrison and Transport House had become unreliable patrons. A quick fix was what Wilson urgently needed: if Transport House had been able to provide one he might have been interested. In the absence of one, he had to take account of the changing political conditions. Bevan offered a possible solution. He did not follow Bevan because of his constituency predicament. But he was well aware that, if it came to the crunch, a pro-Bevan stance was likely to make him a good deal more marketable.

Wilson got little credit for his resignation, at the time or later. Although it was on a point of principle, most people did not regard it as genuinely ‘principled’. Probably, few resignations are: scratch the surface of most outwardly ‘principled’ resignations and you find, alongside the point of principle, a thwarted ambition, a clash of personalities, or a simple weariness and desire to quit. Enough has been said about Wilson’s behaviour to suggest a mixture of motives. However, the conventional view that he did not start moving leftwards until after he resigned is wrong.

‘He did not emerge as a questioning figure until he decided to leave the Government,’ says Jo Richardson, then Secretary of the Keep Left Group.46 In public, this was true. But there had been a period of growing restlessness. When he resigned, he was still a young man and – in many ways – an unformed one with, for a politician, an unusual lack of political experience. Psychologically, he was on the move: some time before the health charges crisis, the transformation from Wilson the bureaucrat to Wilson the polemicist and agitator had begun. He had never broken ranks as a minister, but he had taken the left-wing position in the Government on steel nationalization, and on expenditure cuts. More important, ‘The State and Private Industry’, which he had written and presented to colleagues nearly a year before resigning, was emphatically a questioning document, of a distinctly leftish kind. The April 19 51 row took him one stage further, and provided a kind of blooding.

Until the late 1940s, Wilson’s world had been peopled by dons and civil servants. He did not undergo the apprenticeship which is the lot of nearly all successful politicians in normal times, of passionate argument and factional disputation among the rank and file outside Parliament, and later on the back benches within it. He read, he absorbed, he remembered, he discussed with officials and fellow ministers, he spoke, and he initialled documents. There was little time for anything else, and the world of political ideology was as unimportant as it was mysterious to him. Keen socialists did not so much dislike, as disregard him. ‘He was like an unusually able motor car salesman’, says Freeman, ‘– very bright and very superficial.’ His parliamentary associates, such as they were, mainly consisted of the group of ministers around Cripps. It was here that his political education had begun.

The most attractive and forceful member of Cripps’s circle was Aneurin Bevan. Wilson’s adult experiences had been administrative. But his early ideas of politics had been romantic. Aneurin Bevan offered romance, and radical authority. ‘Nye’s royal command was very hard to resist,’ observes Freeman.47 Bevan took a friendly, avuncular interest in Wilson, and became one of the few politicians (as well as one of the first) to cross the Wilsons’ doorstep in Southway. Long before the resignations, according to Mary, she and Harold got to know Bevan well. ‘Nye was very, very fond of Robin,’ she recalls. He and Jennie came to a fireworks party in Hampstead when Robin was about six – that is, in 1949, during the post-devaluation debate. The Wilsons have a snapshot of Nye in the garden, wearing a black beret and holding a sparkler. Bevan used to treat Harold almost like a child himself, and call him ‘boy’.48

Bevan, too, had his circle – which began to be Wilson’s as well. One of its members was Wilson’s own PPS, the very radical Barbara Castle, who had been closely associated with Cripps and Bevan in the 1930s in the office of Tribune. Castle provided an important link between Bevan and Wilson, with whom she developed a friendship – his closest with any parliamentary contemporary – that lasted for the rest of their linked careers. She introduced Wilson to Michael Foot, another Bevan friend, in 1947.49 People like Castle and Foot were far to the left of Wilson, and were not encumbered by ministerial office. They did not shape his beliefs. But it was in their company, sitting at Nye’s feet, that he learned to be political. Gaitskell’s friends sneered at Wilson’s discovery of ideology; so did many of Bevan’s. Foot, however, believes that it was sincere. ‘You couldn’t have called Harold’s radicalism socialism’, he says, ‘but he did have radical instincts. Like Nye, he wanted things to move, to change. No doubt he also thought there was a real possibility of Nye becoming Party Leader – no doubt he did make that calculation. But he also had a genuine sympathy for him.’50

Wilson was not initially a member of the small group of MPs that identified itself with left-wing causes; and he did not involve himself in the early anti-Gaitskell discussions that preceded the 1951 crisis. At first, the key participant was John Freeman – who, though only a junior minister, had a wider following than Wilson, and was thought by the Left to be a bigger catch. Before long, however, the President was drawn into the group, and began to take a vigorous part.

Freeman himself recalls that, as he began to contemplate resignation, ‘I became conscious of Wilson operating in the same mode on one flank.’ Soon both Wilson and Freeman were attending meetings in the House of Commons and at Richard Crossman’s home in Vincent Square, together with Mikardo, Hugh Delargy, Barbara Castle and other left-wing opponents of the Chancellor’s plans. Some ministers who did not in the end resign also attended. According to Freeman, Sir Hartley Shawcross came to one meeting. Elwyn Jones was sympathetic, and John Strachey, the War minister, ‘wavered backwards and forwards’. The dominating presence was always that of the Minister of Labour. The discussions were about policy. Freeman believed, like Wilson and Bevan, that ‘defence plus welfare was too much for the economy to bear,’ and took the President of the Board of Trade’s advocacy at these meetings seriously. ‘Wilson genuinely had some unease about the economic policy which Gaitskell had been following,’ he considers. ‘It was an area he understood.’ Yet the issue was as much the personality of the Chancellor, as his proposals. ‘One of the bonds between Nye and Wilson’, Freeman now thinks, ‘was that they both saw Gaitskell as the real enemy to their intentions.’51

Bevan was the massive, dominating presence at these meetings:52 but there remains the interesting question of who was leading whom, when it came to the crunch. Wilson claims, and we have no reason to doubt him, that he was desperately uncertain up to the last moment about whether to leave the Government, ‘walking up and down the bedroom floor all night trying to make up my mind’.53 Mary recalls that he said to her: ‘I think I’m going to have to resign.’ She told him that if that was something he felt he ought to do, then he should do so. But she was well aware of his reservations.54 Private uncertainty is one thing, however: in his meetings with Bevan and other allies, he presented a different face.

One newspaper reported on 11 April that Wilson was pressing Bevan to resign;55 and Dalton seems to have formed the same impression. John Freeman, the best available witness, confirms that, by the end, Wilson had become an uncompromising hawk. He remembers a meeting of the three dissident ministers at Bevan’s house in Cliveden Place on the eve of the resignations at which Wilson brushed aside hesitations, saying that things had gone too far to turn back, I think his attitude could be correctly described as “it’s too late for any more shilly-shallying: I’m quite clear we should now resign”,’ recalls Freeman. The issue had become Bevan’s credibility, and whether it could survive the alternative of a public surrender. ‘We all believed in Bevan at the time, and Wilson’s firm judgement of the realities may have been tactically sound and very shrewd.’56 Freeman thinks that Wilson’s influence was decisive in preventing Bevan from pulling back. ‘Probably Jennie’s influence would have been decisive in any case. But Nye had no chance of changing his mind once Harold had weighed in.’57

Publicly, however, Bevan was the leader, and Wilson the barely visible follower. ‘Nye’s little dog’ was Dalton’s contemptuous tag, and it seemed to fit. The general view immediately after the resignations was that Wilson had unwisely taken his cue from a much more powerful personality; that he had wrecked his own career; and that he was, in any case, no great loss to the Government. ‘Mr Wilson’s action had the appearance of making the rift in the Cabinet more serious,’ The Times observed loftily, ‘but this second resignation appears to be treated by the Government and the Labour Party as a matter of no great consequence.’ According to the Manchester Guardian, Wilson had never been more than an adequate debater, and did not have the knack of arousing his own side. Moreover, ‘a certain superiority of manner in debate has not helped his popularity.’ Consequently, he was likely to find himself in the wilderness for some time.58

If, however, the fact of Wilson’s departure led the press to be disdainful, the manner of it was considered impressive. By common consent, Bevan’s resignation speech on 23 April was blustering and self-centred, harming his own cause. Wilson determined to do better. Freeman helped prepare the speech. Mary remembers 24 April as a hectic day: Ernest Bevin’s memorial service in the Abbey in the morning, Harold’s resignation speech in the afternoon. Though she did not know it, the two events marked the symbolic end of the old era, and the beginning of the new.

At a PLP meeting in Westminster Hall before the service, Wilson, Freeman, Bevan and Gaitskell all spoke. Bevan was emotional, Wilson calm.59 The contrast was repeated when Wilson rose in the House just before 4 p.m. Where Bevan had hectored, Wilson ‘quietly and sombrely – almost sadly’ read from notes. ‘I will be brief’, he began, ‘and as far as is compatible with the position in which I find myself, noncontroversial.’ His argument closely followed Bevan’s on arms expenditure and the American accumulation of raw materials. He was, he said, ‘strongly in support of an effective defence programme forced on us by the state of the world’, yet adamantly opposed to a minor and unnecessary cut in the social services which was ‘well within the margin of error of any estimates’. He declared his belief (which subsequent events vindicated) that the arms programme could not be carried out, because it depended on a supply of raw materials from abroad that would not be forthcoming in adequate volume; and, therefore, that the Chancellor should have budgeted for a smaller expenditure on arms and a larger expenditure on social services. He referred, as had Bevan, to the breach in the concept of a free health service: he ‘dreaded how the breach might be widened in future years’.60 In one sense, like Bevan, he took his stand on principle; yet, in another, he was objecting to the elevation of a technical detail into a point of principle, where no principles were at stake. (He was to employ much the same argument against Gaitskell in the Clause IV and unilateralist arguments almost a decade later.) To those who cried ‘principle’ he replied, in effect, with a principled rejection of bad tactics, and of the presentation of a policy, the broad line of which he agreed, in terms that provoked unnecessary conflict. Instead of offering, as Bevan had done, a clash of rival values, he presented himself as an exasperated conciliator regretfully parting company from an inflexible dogmatist.

‘I was never a Bevanite,’ he insisted later.61 In effect, his resignation speech said the same. He made clear his determination to appear the more sober and reasonable of the two Cabinet rebels. Unlike Bevan, he went out of his way to express his regret, and to pledge his continued support for the Government.62 If MPs suspected crocodile tears they did not show it: Wilson’s ten-minute statement was applauded several times. Afterwards, Gaitskell privately contrasted Bevan’s disastrous speech with the speeches of Wilson and Freeman, which ‘were restrained and in a way more dangerous’.63

Wilson’s resignation turned him into a back-bencher for the first time, I am sorry in a way,’ Streat noted at the end of April. ‘Wilson is from many aspects a thoroughly nice young man. He has brains and can work fast and well. I think now he will become just a political jobber and adventurer.’64 It was rumoured in the press that he would contest either East or West Ham at the general election, instead of Huyton, and that he had been offered a directorship in the British film industry at £10,000 a year, double a Cabinet minister’s salary.65 Wilson denied both stories. Before resigning, he had taken care to square his own constituency party, which had passed a resolution condemning the health charges on 15 April. On 5 May Huyton ‘fully endorsed’ his resignation and asked him to stand again at the next election.66 ‘He was given a tremendous reception,’ reported the local press. ‘Cheer after cheer came from the crowded room in Progress Hall, Page Moss.’ Wilson – who by this time had abandoned the search for a bolt-hole – said that he had been asked to stand for other seats, but Huyton remained his choice.67

With this matter settled, he announced that he had accepted an appointment as ‘economic adviser’ by the firm of Montague L. Meyer Ltd, a major timber importer. It was to be a part-time job, with an undisclosed remuneration. Tom Meyer, the head of the firm, described Wilson as a ‘very old friend’ with an unrivalled knowledge of world conditions and trade, who was ‘not only a very fine politician, but a natural businessman’.68 The Financial Times was sceptical. Wilson, it drily observed, ‘has no more knowledge of the timber trade than we have of whether Atlantis ever existed’.69 Wilson remained an employee of the firm for more than a decade, frequently representing it abroad and maintaining links with the Eastern bloc throughout the 1950s, at a time when such contact was rare in political circles, or anywhere else.

The arrangement, which had been agreed in principle before he resigned, secured his future. It gave him an office at Meyer’s headquarters in the Strand and a secretary, at a time when back-bench MPs did not have offices and secretaries; and it gave him a substantial income, for school fees, mortgage repayments and travel, at a time when MPs’ salaries were extremely low. Provided he could stay in Parliament, he was now well placed for the next phase of his political career.

The idea of the Left as a party within the Party was greatly strengthened when Bevan, Wilson and Freeman met the already existing, but hitherto somewhat marginal, Keep Left group of MPs on 26 April. The excitement in some sections of the Movement, and the anger and alarm felt within the Cabinet, reached a new pitch. The Left saw the split as pregnant with opportunity, the Right as a nihilistic bid for power that had to be crushed. ‘Everybody understood the resignations as a tactic to make Nye leader,’ says Freeman.70 ‘People of course are now beginning to look to the future,’ Gaitskell recorded. ‘They expect that Bevan will try and organize the constituency parties against us, and there may be a decisive struggle at the Party Conference in October. We certainly cannot say that we have won the campaign … opinion may well swing over to him. He can exploit all the Opposition-mindedness which is so inherent in many Labour Party Members …’71 The attempt to swing opinion began at once. In May, Wilson addressed a rally at the Theatre Royal in Huddersfield. As he appeared on the stage, the crowd stood up and sang ‘The Red Flag’. ‘This Party of ours, this Movement of ours’, he began, speaking a new kind of language, ‘is based on principles and ideals, and if any one of us when once we feel a principle is at stake … were to cling to office and deny it, then the days of this Party and Labour Movement are over … This Movement of ours is bigger than any individual or group of individuals. It is a Movement which has always allowed freedom of scope, of principles and of conscience.’72 Here was an approach to party discipline that was to have a profound importance in years to come.

Released from government responsibility, Wilson’s style, rhetoric and message were rapidly evolving. He started ‘talking Left’ with a vengeance: urging that money should be spent on poor countries, not on arms, that there should be no pandering to the Americans, and asking whether ‘the underfed coolie’ could be blamed for snatching at Communism.73 On 14 July, the Left published a pamphlet called One Way Only. Its contents were scarcely revolutionary, but because of its authors – who included the three resigners – it deeply embarrassed the Government, and sold 100,000 copies. The pamphlet stressed the world shortage of raw materials (Wilson’s own theme) and the need to restrain prices and spend more on social services. It called for a scaling down of the defence programme, and the need to restrain US foreign policy – especially over the rearming of Germany.74

During the summer and early autumn of 1951, the Government behaved more and more as if it were under siege. The breach in the Party widened, but the great uprising of Labour MPs which Bevan had hoped for, never happened. The Korean War stabilized, and the threat of an American-led invasion of the Chinese mainland receded. There was no new legislation of significance. Wilson busied himself with his Meyer duties, and with a request from the railway trade unions to examine the financial structure of the British Transport Commission.75

On 19 September, Attlee told the Cabinet of his decision to ask for a dissolution. Two days later, the Left published a second pamphlet, Going Our Way. ‘Relations with the Bevanites continue to be very bad,’ Gaitskell had noted the previous month. ‘They are apparently becoming more and more intransigent and extreme. They hope to capture the Party Conference and have, I am told, been forming themselves into a kind of Shadow Government. They no doubt have a considerable following in the constituency parties.’ Gaitskell believed that one factor influencing Attlee in favour of an early election was the hope that it would concentrate the minds of Conference delegates, and smooth over the Party row.76 The tactic was only partially successful. Though Conference in Scarborough was surprisingly united, with Bevan on his best behaviour, the Left made progress in the annual election to the constituency parties’ section of the NEC, indicating a continuing shift in rank-and-file opinion.

In the election campaign, Wilson was fighting for his political life. Defensively, he played down the split in the Party, and denounced what he called ‘the vile whispering campaign’ that he was a Communist or had Communist sympathies.77 Such a campaign, if there was one, appeared to do him little harm. Nationally there was a small but decisive movement towards the Tories, leaving Labour still marginally ahead in the popular vote yet behind in seats. In Huyton, Wilson bucked the trend, and increased his majority – the start of an upward progress (mainly a result of demographic changes due to rehousing policies) that continued to defy national swings, and eventually turned the seat into a Labour stronghold.

Winston Churchill became Prime Minister for the second time, and Labour went into Opposition. For Wilson, however, the outcome was much better than he had reason to hope. If Labour had won, he would have been out in the cold. If it had lost badly, he would have been beaten in Huyton, and would have joined the queue of ex-ministers looking for a seat. As it turned out, he was still in Parliament, everybody in the former Government was an ex-minister, and the resigners were splendidly placed to mount their challenge. His prominence was assured.