Читать книгу Harold Wilson - Peter Hennessy, Ben Pimlott - Страница 14

Оглавление6

VODKA

Gaining a seat in the House of Commons is the most important single event in any British political career. Up to this point, all is fantasy and, from the point of view of nonpolitical observers, vanity. After it, anything is possible. For Parliament is a tiny talent pool, without much talent in it, from which governments of several score ministers are drawn. Anybody representing a major party who enters the Commons, with even a modest amount of vigour and judgement, is likely to achieve prominence sooner or later, if he or she so chooses. Harold Wilson did so choose.

He was also more than modestly equipped. Indeed, alongside the amateurs, dilettantes and semi-retired union officials who made up the bulk of the Parliamentary Labour Party, he was unusually well qualified. Wartime Whitehall had provided an excellent training ground. As a civil servant, he had gained a reputation for his prodigious energy, his appetite for detail, and for a mental agility which some saw as superficial but which was in any case impressive. In a party where formal qualifications were rare but prized, he was one of only forty-six MPs with an Oxford or Cambridge degree. Among this élite group, he had the unusual asset of a regional, non-public school background. He did not – unlike some products of the pre-war universities – carry with him the burden of a Communist or fellow-travelling past. He was also exceptionally young. The 1945 PLP was largely composed of novices: two-thirds of its 393 members were new to the House. Most, however, were already middle-aged. Wilson was one of only half a dozen not yet thirty.

Wilson’s youth and potential were quickly noticed by the press, eager for anything to say about the largely unknown batch of first-time entrants. Echoing newspaper comments before the election, the News Chronicle called him ‘outstanding among the really “new” men on the Labour benches’ and ‘a brilliant young civil servant … regarded by the Whitehall high-ups as one of the great discoveries of the war’.1 He was also noticed by the Labour Prime Minister, Clement Attlee. On 4 August, in a second batch of appointments which followed the premier’s return from Potsdam, Attlee made him Parliamentary Secretary at the Ministry of Works, George Tomlinson. Wilson became the first new MP to be given a job and one of only three new Members to be brought into the Government at the time of its formation.

Why was he singled out? Wilson believed that the Prime Minister’s sentimentality towards University College had something to do with it.2 Attlee gave credence to this view when he told an interviewer in 1964: ‘I had heard of him as a don at my old College and knew of the work he had done for the Party. I therefore put him into the Government at once…’3 Since Wilson had done next to no work for the Party, the college link should presumably be reckoned important. But there were other factors. Wilson was known to Tomlinson, his new boss, who was MP for a neighbouring seat and may have asked for him. He also had an even more powerful patron, later disillusioned, in Hugh Dalton, the newly-appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer.4

Dalton had encountered Wilson as an official in the Mines Department in 1942, and met him again at the 1945 Party Conference, before the election. There was also another meeting, just after the result, at which Wilson acquitted himself well. A few days before the Prime Minister’s offer, Dalton held a private party (later famous among its participants as the ‘Young Victors’ Dinner’) at St Ermin’s Hotel off Victoria Street. To this the Chancellor invited a group of new MPs who had caught his eye. Guests included George Brown, Richard Crossman, Evan Durbin, John Freeman, Hugh Gaitskell, Christopher Mayhew, Harold Wilson, Woodrow Wyatt and Kenneth Younger.5 The majority were public school men, and several had been Oxford-trained dons. Only Brown was not either a recently demobbed officer or a recently discharged temporary civil servant. Most of those present later made their mark, in politics, journalism and diplomacy.

The dinner concluded with a seminar. Dalton asked each in turn to give his views, student-fashion, on the problems facing the Government and the policies which should be pursued. When Wilson was asked to speak, he declared, according to a note made by Gaitskell:

there should be publicity as soon as possible to show that the major difficulties with which we were faced: coal and houses, in particular, were not due to the Labour Government. If possible this publicity should be combined with the announcement of urgent, even desperate measures, to deal with the situation. It would also be helpful to announce at the same time a speed-up in Demobilization. As regards the problem of Redundancy, he would like to see the Government, if necessary, placing orders for refrigerators and vacuum cleaners. He also favoured the maintenance of the guaranteed wage.6

It was not the content of this mundane message, perhaps, so much as the way in which it was argued which created a good impression. We have no record of how the group reacted to Wilson’s rather embarrassing remark that nobody among the new recruits should go straight into the Government, with one exception, ‘on sheer merit: Hugh Gaitskell’.7 Gaitskell did, however, note in his diary a few weeks later that the best contributions to the discussion had come from people he already knew, especially Durbin, Crossman and Wilson. Brown had remained diffidently silent. ‘Perhaps our slightly superior feeling’, Gaitskell observed, ‘was because we had been in the Civil Service all the war and knew rather more about the real problems of the moment.’8 Mayhew, who had not seen Wilson since 1939, remembers being greatly impressed by him on this occasion. Previously, though he had been struck by Wilson’s grasp of complex problems, he had felt able to talk the same language. Now he had a strong sense of the gap in understanding between the ex-Whitehall men and the ex-officers among the new MPs. ‘Compared with people like Wilson and Gaitskell, I felt tongue-tied and ignorant,’ he recalls.9

Gaitskell wrote after the St Ermin’s gathering: ‘I had a curious feeling most of the evening, having always regarded myself as one of the younger people in the Party, I now suddenly seemed to be one of the older.’10 On all counts, Wilson was the most threatening of those present: one of the sharpest, best informed and youngest, and also (by the time Gaitskell wrote his account in early August) the only minister. Although Gaitskell himself was not immediately available for office because of a recent heart attack, the watchful rivalry between the two men had already begun. Wilson, who thought about such things a great deal, must have been pleased at his head start.

The other two new recruits to be given posts were Hilary Marquand, also a former don and temporary civil servant, and George Lindgren, a trade unionist; both were fifteen years Wilson’s senior. ‘I am not sure that this was really good for any of them,’ Dalton wrote of the three appointments in his memoirs, with Wilson probably most in mind. ‘But there were a lot of posts to fill and not a great array of possibles among the old brigade.’11 Apart from Gaitskell (convalescing), Crossman (distrusted by Attlee) and Durbin (whom Dalton picked as his Parliamentary Private Secretary), Wilson had the best claim in terms of proven ability and experience, and his appointment, therefore, should not be seen as a casual one. Significantly, Emanuel Shinwell, the new Minister of Fuel and Power, asked for him – too late – as his PPS.12 Wilson later claimed that he never expected to be a minister for many years. In fact, that would have been surprising.

It would also have been surprising if, as the youngest member of the Government, Wilson had not rediscovered his childhood dream of one day becoming a prominent Cabinet minister – Chancellor of the Exchequer, or perhaps Foreign Secretary. ‘Harold had leadership ambitions from the day he entered Parliament,’ says Harold (now Lord) Lever, who came in at the same time.13 He was not the only one. ‘There’s no point in going into Parliament unless you have the intention of becoming Prime Minister,’ Patrick Gordon Walker, another Oxford don, wrote in his diary just before entering the House in an autumn 1945 by-election. ‘Clearly this is what I must go for. I think I’ll lie low for five years or so & get myself well in with the Party.’14 Perhaps every new MP has the same fantasy. A difference between Wilson and most of his contemporaries, however, was that he began his political career already one rung up the ladder.

Though only a parliamentary secretary, Wilson had a major job. The war had turned Works, in effect, into a Ministry of Reconstruction, charged with finding ‘homes fit for heroes’ and for bombed-out families.15 It appointed the government architect, with influence over all new public buildings, and was required to ensure that as many houses were built as possible, with a maximum of efficiency, using the best materials. The wartime and early post-war ‘pre-fabs’ had been a Works responsibility. The difficulty was a shortage of materials and skilled labour. Obtaining bricks was a particular problem, because production had been greatly reduced under concentration schemes during the war.16 The Ministry’s duties dovetailed with those of the Ministry of Health where Aneurin Bevan was Minister. Bevan set up a Housing Executive, composed of ministers in the three relevant departments: Health, Town and Country Planning (of which Lewis Silkin was head) and Works. Wilson represented Works, bringing him closely into contact with Bevan for the first time.17

In the post-194 5 period, Aneurin Bevan was at the height of his powers and of his influence over the nation’s affairs. A Welsh mining MP who had been elected to Parliament in 1929, he had emerged during the 1930s as one of the most forceful leaders of the Labour Left, with a power of oratory widely compared to that of Lloyd George, and an ability – unique among trade union MPs – to charm left-wing intellectuals and influential plutocrats (such as Lord Beaverbrook) alike. He was married to Jennie Lee, a former ILP ‘Clydesider’ MP, who lost her seat in 1931, and returned to the House fourteen years later. Jennie Lee spent the 1930s outside the Labour Party. In 1939 Nye joined her in exile, following his expulsion with Sir Stafford Cripps, for defying an NEC prohibition of the Communist-led Popular Front movement. Although, with the backing of the left-wing Welsh miners, he was soon readmitted to the Labour Party, he spent the war on the back benches, as one of the Coalition Government’s most dangerous critics.

In 1945, Attlee – who privately admired him – took the courageous step of bringing him straight into the Cabinet. As the head of a major department which provided the spearhead of Labour’s social revolution, Bevan came into his own – directing his imagination and political flair towards implementing the most important of the ‘Beveridge’ reforms, the creation of a free health service. Yet Bevan was never an easy colleague. Although at first a loyal enough member of the team, he remained a not-quite-dormant volcano, liable to erupt at any provocation. Fellow ministers were wary of his egotism, scared by him, in awe of him. Since he was also the youngest member of the Cabinet in the Commons, he was marked out early on as a possible future leader and prime minister. He was, in almost every conceivable respect, an opposite political personality to Wilson. It is no wonder that Wilson was fascinated by him.

Wilson made his maiden speech, a very boring one, in October. One of his ministerial tasks was to restore the Chamber of the House of Commons, which had been destroyed by enemy action. His meandering and apologetic address on this theme was sharply attacked by back-bench MPs including Labour ones, who were unhappy about the facilities available to Members.18 Subsequent performances were scarcely better. ‘When he came into the House, he couldn’t speak at all,’ Woodrow (now Lord) Wyatt recalls.19 Few contemporaries would disagree. In his early years as a minister, his dullness as a speaker became almost as legendary as his precocity.

Wilson had been appointed for his technical grasp, not his speaking ability. He proceeded to throw himself into the details of his brief with Beveridge-like thoroughness, embarking on a nation-wide tour of local authorities, accompanied by employers in the building industry and by trade unionists, to see the problems for himself. He had done much the same in 1937–9, studying unemployment figures in local labour exchanges; now, however, he had a retinue of officials, and the attention of the media. The publicity was good, whatever the effects. When he eventually changed jobs in 1947, he was described admiringly in the press as a ‘hustler’, who had earned praise ‘when he formed a one-man ginger group to spread the housing drive’.20

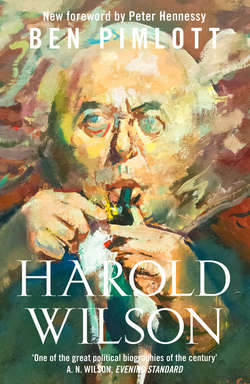

Eager beaver: Wilson as Parliamentary Secretary, Ministry of Works, drawn during a trade dinner in November 1945

Health was a more powerful ministry than Works. More important, Tomlinson was no match for Bevan in ministerial fights. Consequently, rivalry between the two departments soon disposed of attempts by the Ministry of Works to become a ‘giant housing corporation’.21 Wilson, who lacked any political standing, discovered that the scope for effective co-ordination of the building programme was limited. Douglas Jay, who entered Parliament at a by-election in 1946 and briefly deputized for the young parliamentary secretary while he was abroad, found it ‘an impossibly difficult job’, made harder by the refusal of the Cabinet Secretary, Sir Edward Bridges, to permit a junior minister at Works to attend relevant Cabinet Committees.22

Yet to friends, Harold seemed to be hugely enjoying himself. Arthur Brown remembers meeting him in 1946 or early 1947, after a long gap, and finding him as cheerfully bumptious as ever. Brown did not feel that politics had changed him much. ‘He was still a sort of eager beaver who told you all about what he was beavering away at,’ says Brown. ‘He did not emanate any burning passion. What he communicated was that he was very much wrapped up in how to be a junior minister, how to run a committee system and how to get things sorted out. He was mainly interested in the machinery of government – he told me he had set up a bottom-kicking committee. I was reminded that he was very clever and was happy to let you know it.’23

Wilson made a good impression on senior ministers. In May 1946, nine months after his original appointment, George Tomlinson told him that he was about to be moved sideways to the junior post at Fuel and Power, a department in which he had a special interest. Coal production was a mounting worry (within a few months it was to be a desperate crisis) and it was felt that the minister in charge, Shinwell, needed expert help. Wilson was delighted, and cancelled an official trip in anticipation of a call from Downing Street. However, the expected change did not happen, and Gaitskell (still on the back benches) got the Fuel job instead, apparently because Shinwell put his foot down. He had wanted Wilson as his PPS, but, according to Gaitskell, ‘he did not want anyone who was supposed to know about Mining to be his Parliamentary Secretary!’24

Wilson also came quite close to getting a job at the Treasury. Hugh Dalton decided after a year as Chancellor of the Exchequer that he needed an extra minister under him, and sent a personal note to Attlee to this effect. ‘On need for another person/s at Treasury’, he wrote, ‘I would like Harold Wilson to come in as Financial Secretary. He is very able, and has learnt a lot at the Ministry of Works. He does not yet give a very confident impression in the House. But I am confident that I would soon make him confident.’25 A week later Dalton told Ernest Bevin, the Foreign Secretary, of his proposal ‘that I should be given a third minister at the Treasury, preferably Harold Wilson’. Bevin’s reply suggests a high opinion of the young minister’s abilities. The Foreign Secretary expressed a hope that the Chancellor ‘wouldn’t anyhow take Harold Wilson from Works, unless George Tomlinson could have a good man in exchange’.26 The extra post was not created, however, until after Dalton’s departure from the Exchequer, when the Treasury’s powers were widened.

Attlee had other plans for Wilson. A few weeks later, the young minister was despatched to Washington to lead the British team at a Commission of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations. The Commission began work in October 1946, and adjourned at the end of the year. Wilson found it a valuable training session, introducing him to Third World development problems, in which he later took a close interest when in Opposition. The trip also had the incidental, but important, effect of bringing him into close touch with Tom Meyer, head of Britain’s biggest timber importing firm, Montague L. Meyer Ltd. Wilson was keen to increase imports of softwoods for the building programme. Meyer, who was in North America at the same time, helped to provide useful contacts.27

The Commission’s report was presented to Parliament in January 1947. Early in February, Wilson opened the Commons debate on the FAO rather more successfully than he had made his maiden speech. The Daily Herald, Labour’s tame newspaper, called him ‘probably the best ministerial authority on this subject’ (in fact he was the only one), and tipped him for high office.28 A month later came his first promotion. In a reshuffle of junior ministers at the beginning of March, little noticed because of the gathering fuel crisis set off by an exceptionally bad winter, Wilson was made Secretary of Overseas Trade, under Sir Stafford Cripps as President of the Board of Trade, replacing Marquand, who became Paymaster-General.

Although still a junior post, Wilson’s new job was a vital one in the economic conditions of the late 1940s. The Overseas Department, one of the four principal sections of the Board of Trade, was concerned with export promotion and licences, trade treaties and agreements, and commercial relations with foreign countries.29 Wilson’s job involved some routine tasks, like sorting out the request from the MP for Dudley, Colonel George Wigg, for a licence to import sea lions from the United States for Dudley Zoo (one of the beasts was named ‘Harold’ by its grateful keepers).30 But its most important feature was the wide responsibility it gave him in the key area of exports. It offered travel, promising the publicity which always attended foreign visits. And it made Wilson deputy to Cripps, the most dazzling star in Labour’s firmament, and currently in the ascendant.

Cripps was the minister most admired by Labour’s intellectuals. Across the political spectrum, he was regarded as alien, mysterious, almost saintly. In the 1930s, Cripps had been the ‘Red Squire’. A rich, successful barrister, he had originally been co-opted into Parliament by Ramsay MacDonald as a law officer. Following the 1931 crisis, he underwent a conversion to left-wing socialism, and led a series of rebellions against the Party hierarchy which culminated in his expulsion, with Bevan, in 1939. Unlike Bevan, Cripps did not come back to the Labour Party until shortly before the break-up of the Coalition in 1945, having spent the war as an Independent. Yet he had lost none of his standing in the House or the country and – having accepted a succession of key ministerial and diplomatic posts from the Prime Minister – he even appeared at one time as a ‘Churchill of the Left’ who might some day become a challenger for the highest office. By 1945, practical experience had mellowed some of his political beliefs and reduced the number of bees in his bonnet (as Gaitskell called them), but it had not softened his arrogance, or reduced his determination to pursue whatever course he deemed to be right, come what may.

Wilson had solid experience of serving a self-punishing egomaniac much older than himself. To Beveridge-like asceticism and masochistic work habits, however, the President of the Board of Trade added a higher, more visionary idealism, and an ability to command the loyalty of subordinates. Officials appreciated his clarity. So did Wilson. ‘Cripps’s aloof command of detail, his scientific education and knowledge, his administrative genius, his belief in bureaucracy, his patriotism, his Christianity and even his vegetarianism’, as one of Wilson’s earlier biographers puts it, ‘combined to make what Harold Wilson regarded as the perfect politician.’31 Far more than Bevan, whom Wilson always admired but who had many weaknesses, Cripps became Wilson’s political hero, and the closest to a model of how he would like to see himself, and be seen.

At first, Wilson had little to do with his new chief. His immediate assignment was to go to Moscow, where Ernest Bevin was seeking an agreement on Germany. Having just suffered a bout of heart trouble, the Foreign Secretary was considered to be in need of assistance. Wilson was instructed to join Bevin in Russia and take over from him when he left, negotiating on trade.

Accompanied by his personal assistant, Eileen Lane, and a small group of civil servants, Wilson arrived in Moscow on 18 April. Bevin departed shortly afterwards, leaving the young minister – a politician for less than two years – to negotiate on his own. The Soviet trade negotiator was Anastas Mikoyan, an Armenian Houdini who survived innumerable purges and eventually became President of the USSR. Wilson seemed to establish a rapport with Mikoyan. This may simply have been because Mikoyan was adept at handling impressionable young foreigners. Transcripts of their discussions in the Public Record Office, however, show that Wilson had a remarkable command of the details of Anglo–Soviet trade, as well as an impressive bargaining toughness.32

There was one curious, and still mystifying, aspect of the talks. It has since emerged that Wilson suceeded in offending, and even in puzzling, some officials and senior members of the military establishment because of his alleged readiness, during these and later talks, to supply the Russians with jet engines and aircraft that were considered security-sensitive. The mystery, however, concerns the attitude of Wilson’s critics, rather than the minister’s behaviour. The public records do not yield every secret (much of the material remains classified), but they contain enough to show that Wilson, new to his job, referred every major decision back to London, and simply obeyed instructions. At issue were thirty-five Derwent and Nene engines from Rolls-Royce (a continuation of an order already in execution) and three Vampire and three Meteor aircraft. The official record of the April 1947 negotiations indicates that the only security concern of the Air Council at the time concerned delivery dates. Although Wilson proposed that Cabinet should consider improving on them, ‘No promise of any such improvement’ (according to a Foreign Office minute) was made in Moscow. Concessions on delivery dates were later made, but only after Sir Stafford Cripps, as President of the Board of Trade, had personally considered the matter. It is clear that Wilson badly wanted to use the Soviet request as a bargaining chip, but equally clear that he did so only on the basis of close consultation with Cabinet colleagues, including Attlee as well as Cripps.33 Nevertheless, the ‘jet engines’ incident was not forgotten, as we shall see.

After preliminary skirmishes, Wilson flew back to London and returned again to Moscow in June to negotiate in earnest. The British wanted wheat and coarse grain, the Russians wanted engineering equipment, transport vehicles and additional concessions on the delivery of jets. Wilson found Mikoyan an even more intransigent negotiator than in April, and was amused by what he regarded as the Armenian’s oriental wiles. Later he would proudly recount how, faced with a diplomatic attack in the form of a sixteen-course banquet and a steady flow of vodka, he had retaliated by drinking the Soviet delegation under the table.34 In an attempt to obtain an agreement, Wilson cabled home for Cripps’s view in the hope of getting Cabinet approval for a further concession on the delivery date of jets ‘to throw into the pot’. But both the Air Ministry, and the Americans, objected.35

The talks came to nothing and Wilson left empty-handed. To add injury to insult, the plane carrying the British party over-ran the runway at London Airport and crashed into a hedge, cracking one of the Overseas Trade Secretary’s ribs. ‘Things some ministers will do to get publicity,’ said Cripps when he read about it in the newspaper.36 The press attention did Wilson no harm, however, and provided a peg for admiring profiles, linked to the human-interest story of a near disaster. Noting that the young minister was ‘swiftly recovering from the shake-up he received’, the Daily Telegraph described him as ‘an outstanding example of the Socialist intellectual … Able and ambitious, Mr Wilson has been consistently tipped for high office.’ But it also added a note of warning: ‘His frequent trips abroad have not given him time to gain a wide circle of friends in the House. This probably accounts for his reputation for being a trifle aloof.’37

‘It was not Britain’s fault we did not get an agreement in Moscow … ,’ Wilson told guests at a dinner in Liverpool. ‘We missed an agreement by the narrowest of margins, and it was not on trade but on finance that the negotiations broke down.’38 He gave details to Raymond Streat, a Lancashire industrialist who was Chairman of the Cotton Board, and with whom he had dealings in another sphere of his ministerial life. According to Streat, who kept a diary, ‘Wilson’s stories of the life of a Western negotiator dealing with the Russians in Moscow includ[ed] the usual ingredients – tortuous negotiations, false statements, translations to a Russian who inadvertently shows that he understands English, spies and spying.’ Agreement, Wilson told Streat, had been tantalizingly close.39 Cripps remained optimistic. He rang Dalton the day his junior minister returned and told the Chancellor he had not ‘yet given up hope of fixing something with the Russians in spite of Harold Wilson’s failure to get an agreement’.40 The Overseas Trade Secretary determined to do better next time.

It was Cripps who turned Wilson from a diligent, mainly backroom politician, unknown in the country and largely unknown in the Commons as well, into a national figure. He did so on the back of his own, still soaring, ambitions.

Although Sir Stafford Cripps had entered the Government in 1945 with a post not normally seen as one of the most important in the Cabinet, he was regarded from the outset as a member of Labour’s Big Five, together with Attlee, Morrison, Bevin and Dalton. He was also seen as the most left-wing because of his pre-war record of dissidence and his long association with Aneurin Bevan: though, in practice, this reputation was now sustained mainly by an uncompromising temperament. In policy terms, Cripps had set aside his earlier amalgam of Christian ethics and old-fashioned Marxism for the newfangled religion of macro planning. It was in Cripps’s proselytizing planning phase that Wilson first encountered him.

By mid-1947, much of what the Labour Government had set out to do had been achieved, or was in train. Such progress as had been possible in reconstruction and social policy, however, depended on a large US and Canadian loan, which was fast running out. Deepening economic problems made worse by the fuel shortage built up into a sterling crisis, culminating in the suspension of convertibility in August. With the Government’s policies in disarray, and warnings from bankers and industrialists of impending economic collapse, Cripps – as President of the Board of Trade, and minister responsible for the export drive – launched a crusade within the Government for a new strategy based on co-ordinated planning. He also began to think seriously about toppling the Prime Minister.

In the spring, Cripps began to campaign within the Government for a strong minister – either Ernest Bevin or himself – to take responsibility for economic planning. At the beginning of September, after the crisis over convertibility had raised the stakes, he decided to pursue an even more dramatic change: the replacement of Attlee by Bevin at No. 10, in the hope that Bevin would bring about necessary reforms. To this purpose, he proposed to Dalton a deputation by senior ministers to see Attlee, and force his hand: what today would be called a ‘men in grey suits’ meeting. The Chancellor offered his support, but expressed his doubts about Morrison’s likely attitude. The doubts were justified: Morrison had strong objections to a key part of the plan. He agreed that Attlee should be persuaded to stand down but did not agree with – indeed was seriously put out by – Cripps’s suggestion of the Foreign Secretary as successor. ‘Cripps had put the case to M’, Patrick Gordon Walker, Morrison’s PPS, noted, ‘& M had agreed that PM ought to go – but M thought he himself had better qualifications than Bevin.’41 Cripps, however, was not deflected from his purpose, and on 9 September he boldly confronted Attlee with his idea that Bevin should take over as Prime Minister, with the role of Minister of Production as well.

Attlee took no offence. He had long experience of Cripps. He also had better political judgement. First, he asked the Chief Whip, William Whiteley, to see the Foreign Secretary, who denied wanting to become premier and promised to support Attlee.42 Then he bought Cripps off. The President of the Board of Trade had demanded a strong planning machine. To Cripps’s surprise, though not to his consternation, Attlee offered to put him in charge of one. A few weeks later, Cripps became the first ever Minister of Economic Affairs, bringing Cabinet Committees responsible for home and economic affairs together under his own chairmanship, and taking over from Morrison the Economic Planning Staff, headed by Sir Edwin Plowden.43 The leadership crisis was over: Sir Stafford Cripps was now presented as the dynamic force on the domestic side of the Government, with Dalton reduced in standing and Morrison deprived of much of his empire.

The strengthening of Cripps had the immediate effect of advancing Wilson. Cripps remained as President of the Board of Trade until the end of September. In the meantime, Wilson was appointed head of the Export Targets Committee, responsible for the new export drive – part of a trinity of committees designed to deal with the balance of payments.44 This new job brought him to the attention of the sketch writers at a key moment. ‘Wilson was going grey when he was 28’, observed one, ‘and he grew a neat moustache to make him look older. He has a great reputation …’ It is an indication, however, of Wilson’s continuing anonymity that the reporter, who had presumably never met Wilson, had little idea of what he actually looked like. For the same story went on to describe the modestly proportioned politician as ‘big and burly’, and standing nearly six feet tall.45

After the decision to move Cripps had been taken, the question immediately arose of who should replace him as President of the Board of Trade. Wilson was not the inevitable, or even obvious, successor. Yet as the junior minister at the Board with the best knowledge of the export problem, and one who offered no political threat to senior ministers, he was a natural one. As an expert, he had few rivals – and, in Westminster terms, the other economists in the Government were even greener than he was. Douglas Jay had barely been in Parliament a year, and Evan Durbin (Wilson’s successor at Works) had only half a year’s experience of ministerial office. The same was true of Gaitskell who was, however, promoted to take the place of the disgraced Shinwell at the Ministry of Fuel and Power, where Gaitskell had been Parliamentary Secretary. Yet Wilson might have been passed over in favour of the political appointment of somebody better established. What tipped the scale was the recommendation of Cripps himself.

That is Wilson’s own view,46 which was widely held at the time. Attlee later wrote that in bringing Wilson into the Cabinet, he was ‘fortified by Cripps’s opinion’.47 Cripps was not the only Wilson advocate: in a letter sent while on holiday in Guernsey on 15 September, Morrison also put forward the young Overseas Trade Secretary’s name.48 But it was Cripps’s backing that mattered. Wilson’s appointment seems to have been part of a conciliatory package, designed to satisfy the new planning minister’s appetite for power over the economy by surrounding him with younger ministers known to him, whom he could manage. Following Cripps’s critical confrontation with Attlee, Whiteley (the Chief Whip) described what had transpired to Maurice Webb, a pro-Morrison MP, who told Gordon Walker, who reported back to Morrison that Cripps had ‘proposed that Harold Wilson should be at the B of T which would make it a subordinate department under C’.49

After the reshuffle had taken place, Robert Hall, director of the Economic Section of the Cabinet Secretairiat, interpreted the changes in the same way. ‘Cripps has now got three young men whom he seems to trust – in the Board of Trade [Wilson], Supply [George Strauss] and Fuel and Power [Gaitskell],’ Hall recorded. The appointments were to be seen in the context of Cripps’s elevation and tightening grip. ‘It won’t be for lack of power if Cripps fails,’ noted Hall, ‘– he has all the key posts.’50 Dalton must also have been consulted, and seems to have made no objection. Indeed – though one might have expected Wilson’s appointment to cause jealousy because of his youth – it was noncontroversial, and generally approved. Gaitskell, pleased about his own promotion, was happy about this one too. ‘HW was obviously Cripps’s nominee – and a very good one too,’ he noted.51

When the half-expected call came, Wilson was five days into a family holiday in Cornwall, with Gladys, Robin and his parents. He had been spending much of his time in a small boat, setting lobster pots.52 Attlee summoned him to Chequers where, after luncheon, the Prime Minister told him of the Cabinet changes. Cripps was to be economic overlord. Wilson was to succeed him as President of the Board of Trade, the appointment to be made public on 29 September. At the same time, it was impressed on Wilson that he would not inherit Cripps’s former status in the Government. ‘Cripps wants to run the thing with [Wilson], [Strauss]’ (the Minister of Supply), ‘and myself as his lieutenants,’ Gaitskell wrote a couple of weeks later. ‘He made this quite plain to us. We are to have sort of inner discussions on the economic front.’53 Unlike the other lieutenants, however, Wilson was in the Cabinet. At thirty-one, he was the youngest Cabinet minister since Lord Henry Petty in 1806, and the youngest member of the existing Cabinet by a decade.54

It was unlikely, his friends agreed, to stop there. Arthur Brown, who had become an economics professor in the North, wrote a cheerful letter, comparing Wilson to Gladstone, early in the former Prime Minister’s career. G. D. H. Cole congratulated himself on having talent-spotted Wilson in his infancy, and asked if he had yet decided when he was going to become Prime Minister. Even Beveridge managed to be effusive – though, in reply, the young President of the Board of Trade could not bring himself to address his former employer by his Christian name. Wilson also received a letter from Helen Whelan, his former class mistress at Royds Hall, reminding him gently of his prediction in an essay written in 1928 that he would be Chancellor of the Exchequer a quarter of a century later. Wilson replied that he still had six years to go.55

The reaction of the press was generally one of puzzlement although, because there was a Labour government, journalists had become used to odd-looking appointments. Despite the occasional plaudit, the lobby had paid little attention to Harold’s progress on the inside track. ‘Mr Wilson is not a brilliant speaker and his House of Commons performances are no more than adequate,’ judged the Manchester Guardian. ‘It is for his departmental work that he receives promotion.’56 The Observer (profiling him a few months later) agreed that he was ‘not a natural orator’, but predicted a great career for him as one of the future leaders of the Party. It counted it an advantage, as far as the approval of rank-and-file trade-unionist MPs were concerned, that – though brainy – he was not an intellectual in the normal sense, and ‘has none of [John] Strachey’s lucid grasp of Socialist theory’. There was a debate about his accent. The Observer considered his speech to be hybrid, its Northern origins flattened but not hidden by his education. ‘Through the Oxford voice’, it noted, ‘there still was to be heard, faint but unmistakable, the trace of a Yorkshire accent, broadening the vowels, thickening the words.’57 The Manchester Guardian, on the other hand, considered that ‘Oxford has affected neither his manner nor his speech.’58 Both suggested that it helped in Labour terms that, for all his brainpower, he came from an ordinary, unpretentious background.

Other papers stressed his exceptional academic qualifications. Yet what was really remarkable about Wilson was his invisibility. He had risen far and fast without any kind of Labour Party following, within Parliament or outside it. He simply got on with the job, much as he had done in the civil service. He did not have the time, or yet the inclination, to be companionable, and there were many MPs and journalists who were unaware of his existence. According to the Observer, when he entered the House, he had seemed ‘modest to the point of apparent timidity’ (which is not exactly how Oxford or Whitehall contemporaries saw him) and it was ‘difficult to identify him with any of the younger men’.59 He did not cultivate the newspapers. Trevor (now Sir Trevor) Lloyd-Hughes, a Liverpool Daily News reporter who became Wilson’s friend and later his press secretary, recalls him as ‘very shy and remote in those days. He seemed to hide behind pillars in the House and, unlike most politicians, he did not relish talking to lobby correspondents. He seemed to glide around, and did not want to meet people. He was not very likeable and made terribly boring speeches.’60

The shrewdest assessment of the new Cabinet minister was given by Raymond Streat, the Cotton Board Chairman, ten days after Wilson’s appointment. Streat saw him as essentially nonpolitical, in contrast to his predecessor, who would remain in overall charge:

He is quick on the uptake – too well versed in economical and civil service work to rant or rave like a soap-box journalist … Wilson feels no duty to his party to take a political line. So he lets his mind work on lines that come naturally to a young economist with civil service experience. We shall get on easily with him. He is less aloof than the man of austere principles, fanaticism and Christian ideals with whom we had dealt since 1945 – but Stafford will be in effect Wilson’s boss.61

It was as if, because of a difficulty over faulty wiring, the Board of Directors had decided to co-opt the company electrician. He had been brought in to provide technical expertise which the Government needed in order to sort out its economic problems at an exceptionally difficult time.

These problems took a new political turn six weeks after Wilson’s appointment, when Dalton resigned abruptly as Chancellor. Cripps replaced him, but without relinquishing his own recently acquired powers as Minister of Economic Affairs. The brief division between financial and economic governmental powers ended, with a sigh of relief in the Treasury: it was not to be restored until Wilson himself became Prime Minister in 1964. The immediate effect was to make Cripps the third most powerful member of the Government, after Attlee and Bevin. It also gave the new Chancellor less time for direct supervision of the ‘lieutenant’ ministers appointed earlier in the autumn. Wilson had been put at the head of a powerful ministry, which was intended to become the satrap of the even more powerful Ministry of Economic Affairs. Instead, he found himself left to his own devices much more than he had expected.