Читать книгу Harold Wilson - Peter Hennessy, Ben Pimlott - Страница 6

ОглавлениеForeword

by Peter Hennessy

‘In the cycle to which we belong we can see only a fraction of the curve.’

So wrote the statesman and novelist John Buchan of The Thirty-Nine Steps fame.1

Harold Wilson dominated the political curve during my late adolescence and early manhood and, later, my first years as a journalist. To borrow Winston Churchill’s line on Joseph Chamberlain, Wilson made the political weather2 for the great bulk of his thirteen years as leader of the Labour Party between 1963 and 1976, during which he won four of the five general elections he contested and occupied 10 Downing Street from October 1964 to June 1970 and from March 1974 until April 1976.

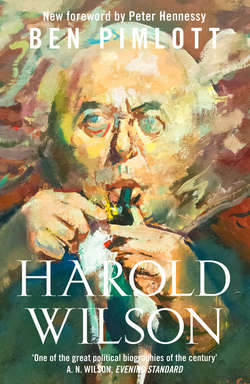

The UK and its politics have travelled a huge arc on Buchan’s curve since Harold Wilson gave way to an older man, Jim Callaghan, as leader of the Labour Party and Prime Minister in the spring of 1976. Ben Pimlott’s fine biography described that curve superbly up to 1992. It was an instant classic and has become an enduring one from one of Britain’s master biographers of the post-war years, and it is a great sadness to me that Ben is not here to update it to mark the centenary of Wilson’s birth.

How do the politics and policies of the years of the Wilsonian ascendancy strike one now? Excessive hindsight can be a historical blight; but fresh perspectives shaped by elapsed time are a stimulating part of the historian’s tradecraft. For example, there are in the middle of the second decade of the twenty-first century plentiful resonances from all phases of the Wilson years, between his succeeding Hugh Gaitskell as Labour Party leader in 1963 and his final handing in of his seals of office to the Queen in 1976.

Merely to list some of them tells a story:

• The internal condition of Labour; the tussles between its competing philosophies and factions; the party’s relationships with the trade unions and constituency activists.

• Europe and the referendum question; Britain’s place in the wider world; of punching heavier than its weight3 militarily and diplomatically, plus the deployment of soft power, with the often neuralgic sub-theme of The Bomb and remaining a nuclear weapons state always a lurking question.

• Employment, productivity, the imbalance between finance, services and manufacturing; the state’s role in shaping an industrial strategy and sustaining the country’s scientific and technological base; plus the UK’s thinking above its weight in terms of research and the universities.

This inventory is by no means complete, and how it would intrigue Wilson to revisit it as he absorbed the current scene through the clouds of his trademark pipe smoke were he still with us.

In his absence, let us linger on a few key Wilsonian themes. First, Labour Party management. Wilson was a supple and serpentine party manager. He was a quantum physicist among politicians in his understanding of what it took to keep its volatile subatomic particles together. For these gifts he was often derided – dismissed as a tactician who would all too readily sacrifice long-term strategy to the imperative of the immediate and the pressing. But now, at a time when the Corbyn-led Labour Party is demonstrating fortissimo its most powerful centrifugal tendencies, to the detriment of its indispensable constitutional function of providing sustained and effective opposition to the government, Harold-the-party-manager seems positively lustrous – a reminder that at least a semblance of party coherence is more often than not a first-order matter for Labour. The party’s relations with the unions and the wider Labour movement are integral to this.

Wilson knew how to juggle with and arbitrate between the political philosophies that perpetually compete for the soul of the Labour Party: social democracy; democratic socialism; and a variety of hard-left factions. This skill was matched by his sense of party structure: the constituency membership base and its affiliated trade unionists; the relationship with the Trades Union Congress; the Parliamentary Labour Party; the Shadow Cabinet and the Party’s National Executive Committee and its annual conference. His word power, his sharp wit and his plethora of personal relationships enabled him to pursue his ambition, with considerable success, of turning Labour into the natural party of government, rather than operating in ‘a Conservative country that sometimes votes Labour’, as Reggie Maudling, a former Tory Chancellor of the Exchequer, liked to put it.4

For all his striking achievement in the course of a single summer in 2015 in capturing the base and the leadership apex of the Labour Party (with considerable support from the leaders of the fewer yet larger conglomerate trade unions), Jeremy Corbyn is simply not in the Wilson class. Crucially for Corbyn, his wit, his style, his policies simply do not run in the crucial middle, including the bulk of the PLP. In terms of jumping and clearing the Labour Party’s internal fences, Wilson was a Grand National winner; Corbyn has yet to win a local point-to-point. The gap between them as parliamentary performers in the House of Commons similarly yawns chasm-like. Wilson was born to excel at Prime Minister’s Questions.

Their pre-leadership formation and experience also make for the starkest of contrasts. Wilson, like the classic scholarship boy he was, had prepared meticulously for the Labour leadership and ultimately for the premiership. He knew the Civil Service intimately as a temporary official in the War Cabinet Office,* and rose rapidly through the junior ranks of the Attlee government to become President of the Board of Trade in 1947, at thirty-one the youngest member of a Cabinet since Pitt. A seemingly principled resignation in April 1951, alongside Nye Bevan and John Freeman, in response to health service cuts and the cost of rearmament when the outbreak of conflict in Korea chilled the Cold War still further, opened his credentials to the left of the party in a way his previous technocratic prowess had not.

In opposition Wilson shadowed nearly all the big portfolios, including the Treasury and Foreign Affairs, chaired the premier select committee in the Commons (Public Accounts) and taught himself to be a sharp and often bitingly funny speaker at the despatch box and on the platform alike (he had been rather pedestrian at the Board of Trade). He retained his technocratic edge and, as a trained economist and statistician, was numerate as well as literate. By the time of Gaitskell’s sudden and unexpected death, Wilson had all the gifts and fitted to perfection the mould of the gritty grammar school meritocrat – part of the rising generation that would sweep away the last vestiges of amateurism in Whitehall committee rooms and industrial boardrooms alike.

Wilson, however, never acquired the full trust or affection of many of the right of the Labour Party (several of whom thought he took careerism and opportunism to new heights), but he was admired, respected and feared, especially by his opponents. He was a stunningly effective Leader of the Opposition between February 1963 and October 1964. First Harold Macmillan, in his last, no longer ‘Supermac’ phase, and then the aristocratic Alec Douglas-Home were almost out of central casting as foils for Wilson.

Jeremy Corbyn’s CV on assuming the leadership of the Labour Party was entirely lacking in job experience. His apprenticeship placement had been on Labour’s outer-left rim, as narrow and rigid (if principled) as Wilson’s had been wide, fluid and adaptive. He neither planned for nor expected the party leadership. He was without ministerial or Opposition front-bench experience. In the summer of 2015 it merely seemed Corbyn’s turn to be the traditional tethered goat that the Labour hard left offers up for mainstream leadership candidates to savage. Far from being the sacrificial quadruped, he turned out – to his and everyone else’s surprise – to be the lion of the contest. There could not be a greater contrast of formations than between those of Wilson and Corbyn, this intriguing and unproven figure with carnivorous views and herbivorous ways. Jeremy Corbyn may turn out to be a more effective Labour leader than many expect, but his long-term mission, one suspects, will not include a Wilsonian appetite for capturing the centre of the British electorate and turning Labour into the natural party of government. For that to happen, the fulcrum of British politics would have to shift several degrees to the left.

Wilson, however, did set out in the early months of 1963 to offer himself and his party as a transforming instrument to his country. Like Corbyn’s – though in a very different way – his was a transformative pitch, a blueprint (to use a noun fashionable at the time) for a New Britain. If office fell into his and his party’s hands it would not be a status quo or a ‘better yesterday’ (to adapt a phrase of Ralf Dahrendorf’s5) premiership or administration. His stall, which he laid out with great verve throughout the election year of 1964, was both brilliantly simple and fiendishly difficult – to project the British economy onto a new and sustained trajectory of science, technology and export-led growth substantially higher than achieved so far in the years since 1945. Wilson set himself a very high bar against which he and his ministry would be judged, and the brilliance of his language, the grittiness of his style and the seemingly comprehensive approach to ‘purposive’ (a favourite adjective) government and planning plainly persuaded a sizeable slice of the electorate as to its achievability. At the October 1964 general election a Conservative majority of nearly a hundred in the House of Commons was converted to a Labour one of six.

It was a dazzling performance and, for all the frustrations and underachievement that followed, it still has a tingle to it today that echoes in the latest approaches to growth, science and technology and the planning of long-term investment that are the currency of industrial and infrastructural politics in 2016. If Wilson were taking a centenarian’s look at British politics today he might allow himself a dash of I-told-you-soing.

In what I still regard as the signature speech of Harold Wilson’s long political life, he found a theme at the Labour Party Conference in Scarborough on 1 October 1963 that served not only to unite all shades of Labour opinion but also caught the wider appetite for a modernity that would replace privilege with meritocracy. We learned from Ben Pimlott’s biography when it was first published that Wilson did not finally decide on this theme until the night before he delivered his conference peroration, and that he did so at the prompting of his Political Secretary, Marcia Williams, now Lady Falkender.6

Wilson’s speech built upon his analysis of the deeper causes of Britain’s relative economic slippage by providing an outline of the attitudes and the ‘new industries which would make us once again one of the foremost industrial nations of the world’. As Ben wrote, ‘The climax was a declaration that enraptured his audience, made a profound impact on the press, and was frequently to be quoted – at first in his favour and then against him, in later years’:7

In all our plans for the future, we are re-defining and we are restating our Socialism in terms of the scientific revolution. But that revolution cannot become a reality unless we are prepared to make far-reaching changes in economic and social attitudes which permeate our whole system of society.

The Britain that is going to be forged in the white heat of this revolution will be no place for restrictive practices or for outdated methods on either side of industry … In the Cabinet room and the board room alike those charged with the control of our affairs must be ready to think and to speak the language of our scientific age.8

From that autumn day on the Yorkshire coast, any political word-association game would twin ‘white heat’ with ‘Harold Wilson’.

As a country we are still searching for that Holy Grail of full employment, high productivity, export-led prowess sustained by the technical ingenuity and the applied little grey cells of a well-trained, flexible, agile and highly motivated world-class workforce. Today, in, for example, Michael Heseltine’s highly influential report on growth for the Cameron coalition government, No Stone Unturned,9 the ingredients of such a strategy would be different, stressing a far greater charge of private sector input within a public/private mix and no trace of the revived or new state enterprises that animated Wilson’s view from the Scarborough Conference Hall. But the clarion call to embrace new technology and the rekindling of once great industrial powerhouses has more than a dash of Scarborough about it.

The failure to make manifest the promise of Scarborough has blighted Wilson’s reputation from the late 1960s until today, I think now (though once I did not) to probably an excessive degree. It’s not just that Britain or ‘England’, as Disraeli called it, is ‘a very difficult country to move … and one in which there is more disappointment to be looked for than success!’.10 The very nature of the state did not lend itself to becoming the production engineer of such a transformation. We simply did not possess what the economist Chalmers Johnson later called the kind of ‘developmental state’ required.11

In my judgement, Wilson knew this when he rose to bathe his Scarborough audience in the warmth of the ‘white heat’ of the longed-for technological revolution. He said as much in an agenda-setting speech he called ‘The New Britain’ in Birmingham Town Hall on 19 January 1964: ‘We must reconstruct our institutions … This means a new sense of drive in the higher direction of our national affairs; it means changes in our departmental structure to reflect the scientific and technological realities of the new age.’12

For a fundamental change in the structure of Whitehall’s economic and industrial ministries was also central to the plan. In October 1964 he split the Treasury, leaving it a ministry of finance and public spending and placing responsibility for growth and planning in a new Department of Economic Affairs under his mercurial deputy, George Brown, whom he had defeated in the race to succeed Gaitskell. A second new department, the Ministry of Technology, was created as the ‘white heat’ department and placed in the charge of the left-wing leader of the Transport and General Workers’ Union, Frank Cousins. The hope was that these institutional innovations would fuel a take-off for the British economy as laid out in the French-style National Plan unveiled by Brown in September 1965.

A foreword is not the place for an autopsy on the failure of Wilson’s grand design. Ben’s pages carefully and vividly anatomise how it played out, not least how the anticipated ‘creative tension’ between Jim Callaghan’s Treasury and George Brown’s DEA produced more tension than creativity, especially when the showdown came between keeping the pound at $2.80 on the exchanges rather than devaluing and dashing for growth during the economic crisis of July 1966, when the balance of payments (the great economic totem of the age) worsened on the back of a protracted seamen’s strike and the government resorted to deflationary measures and an incomes policy.

Wilson still sought new ways of stimulating the British economy to rise to a higher and more productive trajectory after the setback of July 1966 and the inevitable – but still humiliating – devaluation of the pound in November 1967 from $2.80 to $2.40. With his favourite minister, the dazzling Barbara Castle, at the Department of Employment and Productivity (the old Ministry of Labour by another name), Wilson sought to curb the power of the unions and the rash of ‘wildcat’ strikes that were such a familiar Sixties phenomenon with a set of proposals in a white paper they called In Place of Strife. This went down in flames in June 1969, battered by hostile ordnance hurled by the National Executive Committee, the wider Labour movement and, finally, a Cabinet prepared to settle for a feeble ‘solemn and binding’ undertaking from the TUC to spare no effort in curbing industrial action. The ‘white heat’ speech of 1963 and the promise of 1964 were tarnished for ever.

They were also unfulfilled. As Sir Alec Cairncross, Head of the Government Economic Service from 1964 to 1969, put it in his audit of the British economy since 1945, ‘the target assumed’ by the 1965 National Plan was ‘an average 3.8% rate of growth compared with an average rate of only 2.9% from 1950 to 1964 and a rate actually achieved between 1964 and 1970 of only 2.6%’.13 There was no leap to growth; no new trajectory for the British economy.

Wilson did not reach the benchmark he had drawn for himself and his governments. In pursuit of his grail of growth, Wilson also cut against his own Commonwealth instincts and turned to what at that stage was the unarguable economic success story of the Common Market of the six original members of the European Economic Community led by West Germany and France. He and Brown (moved to the Foreign Office from the DEA after the 1966 crisis) determined to persuade sceptical Cabinet colleagues of the EEC route to economic salvation. They set off for a round of conversations across the European capitals, declaring that they would not take ‘No’ for an answer as Harold Macmillan had been forced to by President Charles de Gaulle of France in January 1963, following the first UK application. De Gaulle rather liked Brown calling him ‘Charlie’ when the Harold and George show passed through Paris – but he said ‘No’ again anyway.

At heart Wilson was a Commonwealth and an Atlanticist man, not a European man. A strong believer in the NATO alliance (very much a creation of Ernest Bevin, Foreign Secretary in the Attlee administration in which Wilson was so proud to have served). Wilson is remembered fondly by today’s Labour left for setting his face against sending British troops to fight in the Vietnam War despite intense pressure from President Lyndon Johnson in Washington, who repeatedly said that even a platoon of Black Watch bagpipers would do. Wilson’s argument was partly that the UK was doing its duty in Asia fighting (and winning) the ‘Confrontation’ with Indonesia.

His handling of the perennial question of Labour and The Bomb was also masterly. Even though it was initially Labour’s bomb (Attlee took the decision to procure a UK atomic weapon in a Cabinet committee in January 1947; though the first test took place under a restored Churchill premiership in October 1952), the H-bomb era brought the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament into existence in 1958, which, briefly, captured the Labour Party Conference in 1960–61. For a time as Leader of the Opposition, Wilson gave the left the impression that though he was a multilateral disarmer, he did not believe Britain should accept the high level of dependence on the United States implicit in the purchase of submarine-launched Polaris missiles in the deal Macmillan struck with Kennedy at Nassau in December 1962. Labour’s manifesto for the 1964 general election, Let’s Go with Labour for the New Britain, said of the new system: ‘it will not be independent, it will not be British and it will not deter’ and pledged ‘the renegotiation of the Nassau Agreement’.14

Yet, in office, he persuaded successive Cabinet committees and finally the full Cabinet that Polaris should be purchased for the Royal Navy, whose submarine service would operate four boats to ensure that at least one was at sea at all times – so-called ‘continuous at-sea deterrence’, which has been maintained from 14 June 1969 to today, ever since the Navy took over the strategic deterrent role from the ‘V’ bombers of the Royal Air Force.15 Once more there are resonances for the present era of Labour leadership. Jeremy Corbyn, currently Vice-President of CND, has been a unilateral disarmer all his political life. His shadow Foreign Secretary, Hilary Benn, and his shadow Defence Secretary, Maria Eagle (at the time of writing), are adherents of the still current Labour policy of replacing the Trident missile-carrying Vanguard-class submarines with sufficient so-called ‘Successor’ boats to sustain continuous at-sea deterrence into the 2050s. Yet the nuclear policy with which Labour will fight the 2020 general election is far from clear given its leader’s connections (he has already made plain he would never authorise its use16) and the party’s current defence review jointly led by Maria Eagle and the anti-nuclear Ken Livingstone. The names may have changed but the nature and line-ups of this debate would be deeply familiar to Wilson.

So would another nerve-stretching element in the 2016 political season – Europe and the referendum. Vernon Bogdanor has made the very shrewd observation that Harold Wilson is one of the very few British prime ministers who has not, in one way or another, been eaten up by the European Question (despite the failure of that second EEC application) because of the way he handled the 1975 referendum on whether the UK should leave the EEC or remain, just two and a half years after acceding to it in January 1973. Bogdanor believes that this was ‘perhaps Wilson’s greatest triumph’,17 a bold claim that has much in it, especially as he also described Wilson’s position on the EEC in the early 1970s as ‘unheroic’. Professor Bogdanor recalled that when Roy Jenkins, then Deputy Leader of the Labour Party, resigned from the Shadow Cabinet in 1972, after Labour promised a referendum on Common Market membership if returned to power, with others following,

Wilson told the Shadow Cabinet that while they had been indulging their consciences, it had been left to him to wade through s**t [to keep the Labour Party together]. Yet Bernard Donoughue, head of Wilson’s Policy Unit after 1974, was surely right to say that while Heath had taken British Establishment into Europe,18 it was Wilson who brought in the British people.19

A justifiable claim given the two-thirds-to-one-third vote in 1975 to stay in. But, as Professor Bogdanor noted, in the run-up to the coming remain/leave referendum in 2016 or 2017, ‘the British establishment remains firmly attached to Europe, even though the people remain full of doubts’.20

The European question has been a near-perpetual of the UK’s national political conversation since Jean Monnet turned up almost out of the blue in London from Paris in May 1950 bearing his and Robert Schuman’s plan for a Coal and Steel Community.21 It has been a particularly vexing element in our political biorhythms ever since, not least because it cannot be cast in the traditional left–right mould that normally shapes our party political competition.

Gazing wider than Europe, how does Harold Wilson fit the standard model of British politics since he entered the House of Commons in 1945? First of all, what is the ‘standard model’? In my judgement, it’s this: post-war UK electoral competitions have seen a jostling for pole position between liberal capitalism (in my view, the best instrument for innovation and economic growth so far discovered) and social democracy (the best mechanism so far created for redistribution and a measure of social justice). The voting public tends to wish for a judicious mix of each, and the job of Parliament and Whitehall is to attempt to achieve this by reconciling and blending these two philosophies. Occasionally, the electorate votes for a sharp dose of one rather than the other.

Early Wilson benefited from a ‘sharp dose’ phase if you take the general elections of 1964 and March 1966 (when Labour’s majority shot up to ninety-seven) together. It was, along with 1945 and, perhaps, 1997, one of the shining opportunities for radical centre-leftist policies in the UK. In June 1970 when, to near universal surprise, Wilson lost to Ted Heath, who was propelled into Downing Street by a Conservative majority of forty-four, it appeared the electorate had plumped for a shot of liberal capitalism (if the Tory manifesto A Better Tomorrow22 was to be believed). But the Heath U-turns, in the face of unemployment nudging a million people (a shocking statistic for the first fifteen or twenty years after the war), rather belied the free-market impulses of the 1970 prospectus.

The general election of February 1974, which Heath called on the back of the second miners’ strike inside two years, did not produce a shining hour for either of the competing political philosophies. Heath went to the country in a mood of ‘Who governs?’, and the electorate replied ‘Not sure’ twice, with Wilson taking office at the head of a minority government in March 1974 and with the slimmest of overall majorities in October 1974. Though his last administration tried to reach a new deal with the trade unions (the ‘social contract’) and offered a mildly interventionist industrial strategy, it was a time for coping, for getting by rather than for white – or any other – heat. With inflation around 25 per cent and the balance of payments reeling from a quadrupling of world oil prices following the 1973 Yom Kippur War, Wilson’s extraordinary array of political gifts was almost entirely devoted to holding the line through yet another incomes policy (which is why it is easy to forget just how skilfully he played his party and the country in the run-up to the 1975 referendum on Europe).

I have concentrated in this foreword on the special selling points Wilson displayed before the electorate in the promising glow of his first leadership of the Opposition and his early days as Prime Minister, as well as the extraordinary feat of party and wider political management he exhibited in 1975 (‘and people say I have no sense of strategy’, he said to his Principal Private Secretary, Ken Stowe, once the result was in23). But rereading Ben’s biography brings back just how relentlessly demanding the job of prime minister is. The crises are endless and Pimlott’s pages crackle with Wilson-the-crisis-manager. There was the perpetual problem of holding the thin red line of the sterling exchange rate in the 1964–70 government, when the seemingly constant balance of payments problems placed, as soon as they seriously deteriorated, instant pressure on the pound as the world’s second reserve currency after the US dollar in that age of Fixed exchange rates From November 1965 there was the running sore of Rhodesia after the Smith government unilaterally declared independence, presenting Wilson in both his Downing Street spells with one of the most stretching problems created by the withdrawal from Empire. And from 1968–69 a recrudescence of the Troubles in Northern Ireland was another great absorber of time and political nervous energy. And all the while, throughout his premiership, the ever-present perils of the Cold War lurked.

It is not surprising, therefore, that when he finally announced he was standing down, just days after his sixtieth birthday, he was worn out – if still chirpy in his pawkier moments – having sat almost continually on Labour’s front bench since the late summer of 1945. His longevity at or near the top of his party, his temperament, his gifts, his cockiness combined with social edginess – the sheer variety of Harolds he could put on display according to need or taste – made him the richest of characters for the biographer’s art. And in Pimlott on Wilson, subject and biographer were supremely well met.

Rereading his Harold Wilson serves only to remind us what a huge loss Ben Pimlott was to the historians’ trade and to political commentary. Tracing the Buchanite curves of contemporary British history as we travel them is so much harder without Ben. ‘What would Ben have made of this?’ is a thought that still crosses my mind when an event breaks or a political shift becomes apparent, as, for example, the weekend in September 2015 when Jeremy Corbyn won the Labour leadership race. But, above all, what would Ben Pimlott have made of the Wilson legacy in the centenary year of Harold’s birth? It is a matter of great regret – personal and professional – that this question must go unanswered.

Peter Hennessy, FBA,

Attlee Professor of Contemporary British History,

Queen Mary, University of London.

South Ronaldsay, Walthamstow and Westminster.

December–January 2015–16