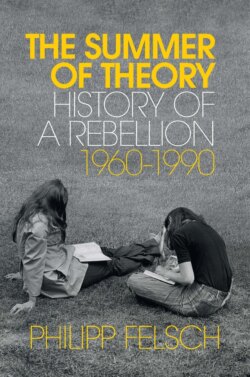

Читать книгу The Summer of Theory - Philipp Felsch - Страница 18

2 IN THE SUHRKAMP CULTURE

Оглавление5 Louis Althusser, Für Marx, Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1968.

It would be some time, however, before philosophy would be swept up in the maelstrom of practice, and before Adorno would be driven from the lecture hall as an obstacle to revolution by bare-breasted student activists. In 1965, theory was ascendant. In the autumn semester, Adorno lectured on negative dialectics: the event had the aura of an important event for German society. He stepped up to the lectern, aided by a female assistant. For the first time, a tape recorder was running to record his message for posterity. Adorno went all out in saying that Marx’s famous Feuerbach thesis – that philosophy’s duty is to change the world – was obsolete. Because theory has not metamorphosed, as predicted, into practice, because it has thus failed to be eliminated, he explained, we must assume once more that theoretical thinking is still current. In a bold figure of speech, he summarily turned Marx upside down: ‘One reason why [the world] was not changed was probably the fact that it was not interpreted enough.’ Only theory that is not immediately aimed at changing the world, his dialectically intricate argument implied, is able to change it at all. And where, if not here, in ‘relatively peaceful’ West Germany, could such a philosophical project find the necessary ‘historical breathing space’?1 It is surprising how benevolently Adorno reviewed German history. Ordinarily, he had been the harshest critic of the status quo, but now he seemed to sense a historic opportunity. The present, he assured the students who packed his lecture hall to overflowing, is ‘the time for theory’.2