Читать книгу The Summer of Theory - Philipp Felsch - Страница 8

Introduction: What Was Theory?

ОглавлениеSentenced to three years’ imprisonment for arson in 1968, Andreas Baader discovered letter-writing. He described the torment of solitude, ranted about the guards, and asked his friends to supply him with essentials. Besides cured meats and tobacco, that meant, most of all, books. He had people send him the student movement’s favourite authors, Marx, Marcuse and Wilhelm Reich, which he had only known from hearsay up to then. ‘Mountains of theory, the last thing I wanted’, he wrote to the mother of his daughter. ‘I work and I suffer, without complaining of course.’ Later, in the maximum-security prison at Stammheim, it was up to his lawyers to feed his hunger for reading material. At the time of his death, there were some 400 books in his cell: a respectable library for a terrorist who was notorious among his comrades for his recklessness. Without a doubt, Baader played the part of a jailhouse intellectual, just as he had previously played the revolutionary. Yet, at the same time, there was a great deal of seriousness in his studies. His letters indicate that he felt a need to catch up1 – after all, the struggle to which he had dedicated himself was founded on theoretical principles.2 In a different time, Baader would have taken up painting perhaps, or begun writing an autobiographical novel. Instead, he plunged – almost in spite of himself – into theory.

Now that the intellectual energies of ’68 have long since decayed to a feeble smouldering, it is hard to imagine the fascination of a genre that captivated generations of readers. Theory was more than just a succession of intellectual ideas: it was a claim of truth, an article of faith and a lifestyle accessory. It spread among its adherents in cheap paperbacks; it launched new language games in seminars and reading groups. The Frankfurt School, post-structuralism and systems theory were best-selling brands. West German students discovered in Adorno’s books the poetry of concepts. As the sixties dawned, the New Left rallied under the banner of its ‘theory work’ against the pragmatism of the Social Democrats: those who would change the world, they proclaimed, must start by thinking it through. But the thinking they had in mind had nothing to do with the philosophy of professors who stuck to interpreting the classic texts or the meaning of Being. It was concerned less with eternal truth and more with critiques of the dominant conditions, and under its scrutiny even the most mundane acts took on social relevance. Jacob Taubes, professor of the philosophy of religion in Berlin, saw his students reading the works of Herbert Marcuse with an intensity reminiscent of the zeal ‘with which young Talmud scholars once interpreted the text of the Torah’.3 On campus, theory conferred upon its readers not only academic capital, but also sex appeal. Marcuse led to Marx, and Marx to Hegel: those who wanted to have a say in the discussion got themselves the twenty-volume Suhrkamp edition of Hegel’s complete works.4 Only after the shock of the terrorists’ debacle in Stammheim and Mogadishu did any doubts about the canon of the ’68 generation mature into open resistance. New thinking came to Germany from Paris and did away with the tonality of dialectics. The books of Deleuze and Baudrillard called for a different kind of reading from those of Marx and Hegel. They seemed to have a more important purpose than the search for truth, and in the course of the 1980s theory metamorphosed into an aesthetic experience. And when ecology laid constraints of quantities and limits on the speculative imagination of the seventies, thorny philosophy set out to infiltrate the art world.

The first impetus to write this book dates from several years ago. In the spring of 2008, the editor of a journal of intellectual history called me to ask for an article on the German publishing house Merve. The editor was planning an issue about West Berlin, the walled-in city on the front lines of the Cold War, which Merve had supplied with theory for twenty long years. Peter Gente, the founder of Merve, had retired from publishing and sold his papers to an archive to finance his sunset years in Thailand, and so the time seemed ripe for historical retrospection.5 Although I wasn’t a Berliner, Merve was a byword to me too. There was no way I could refuse.

Merve has been called the ‘Reclam of postmodernism’ – Reclam, of course, are the publishers of the ‘Universal Library’, the yellow, pocket-sized standard texts that no German student can do without. Merve was the German home of postmodernism, and practically owned the copyright to the German word for ‘discourse’.6 Merve had made a name for itself in the 1980s, primarily with translations of the French post-structuralists. Its cheaply glued paperbacks were a guarantee of advanced ideas, and the pop-art look of their un-academic styling was ahead of its time. The coloured rhombus on the cover of the Internationaler Merve Diskurs series was a well-established logo whose renown rivalled that of the rainbow rows of Suhrkamp paperbacks.

I remember well the first Merve titles I read. It wasn’t easy, in Bologna in the mid-1990s, to get them by mail order. My intention had been to spend a semester there studying with Umberto Eco, but Eco’s lectures turned out to be a tourist attraction. Whatever the famous semiotician was saying into his microphone at the far end of the lecture hall was easier to assimilate by reading one of his introductory books. In retrospect, that was a stroke of luck, because it forced me to look for an alternative. And the search for a more intense educational experience led me – twelve years after his death – to Michel Foucault. My Foucault wasn’t bald and didn’t wear turtlenecks, and although he occasionally spoke French, his Italian accent was unmistakable. But his grand rhetorical flourishes and his tendency to overarticulate his words are engraved in my memory. In his best moments, he came very close to the original. Valerio Marchetti had heard the original Foucault at the Collège de France in the early 1980s, if I remember correctly, and absorbed – as I was later able to verify on YouTube – his way of talking as well as his way of thinking. He was a professor of early modern history at the University of Bologna. His lecture course, which was attended by very few students, was devoted to a topic only a Foucauldian could have come up with: ‘Hermaphroditism in France in the Baroque Period’. I was spellbound on learning of the seventeenth-century debates in which theologians and physicians had argued about the significance of anomalous sex characteristics.7 I had never heard of such a thing at my German university, where philosophy students read Plato and Kant. I hung on Marchetti’s every word, attending even the Yiddish course that he taught for some reason, and started reading the literature he cited: Michel Foucault, Paul Veyne, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Georges Devereux … I waited weeks for the German translations to arrive in the post. I read more than I have ever read since, and collected excerpts on coloured file cards. In the heat of the Italian summer, the ‘microphysics of power’ and the ‘iceberg of history’ stuck to my forearms.8

In 2008, I hadn’t touched these books in years. Their spines crumbled with a dry crackle when I opened them. Inside I discovered vigorous pencil marks, reminding me what a revelation theory had been to me in those days. But at a decade’s remove, that experience seemed strangely foreign: it seemed to belong to an intellectual era that was now irretrievably past. I went to Karlsruhe to have a look at the materials that Peter Gente had turned over to the Centre for Art and Media Technology. In the forty heavy boxes that had not yet been opened – much less catalogued – perhaps I would find a chapter of my own Bildungsroman. They contained the publisher’s correspondence with the famous – and the less famous – Merve authors, along with the paper detritus that lined the road to over 300 published titles: newspaper clippings, notes, budgets, dossiers … While Gente rested, I supposed, in the shade of coconut palms, I immersed myself in his papers. Only gradually did I realize that what I was looking at were not the typical assets of a liquidated business: it was the record of an epic adventure of reading.

The oldest documents dated back to the late 1950s, when Gente discovered the books of Adorno. That discovery changed everything. For five years, the young man ran around West Berlin with Minima Moralia in his hand, before he finally got in touch with the author. By then, Gente was in the middle of the New Left’s theoretical discussions, combing libraries and archives in search of the buried truth of the labour movement. He was everywhere, cheering Herbert Marcuse in the great hall of Freie Universität, demonstrating with Andreas Baader in Kurfürstendamm, running into Daniel Cohn-Bendit in Paris a few weeks before May of ’68. Later, he had discussions with Toni Negri, sat in jail with Foucault, put up Paul Virilio in his shared flat in Berlin. There was never any question that he belonged to the movement’s avant-garde – yet he kept himself in the background. It was a long time before he found his role; he didn’t care to play the part of an activist, nor that of an author. ‘Tried to intervene, but wasn’t able to do so’ was his summary of the year 1968.9

From the beginning, Gente had been, above all, a reader. The scholar Helmut Lethen, who had known him since the mid-1960s, called him the ‘encyclopaedist of rebellion’.10 He knew every ramification of the debates of the interwar period; he knew how to lay hands on even the most obscure periodicals; his comrades’ key readings were selected on his recommendation. Compared with Baader – whom he supplied with books in Stammheim Prison – Gente embodied the opposite end of the movement: the man I met in 2010, and questioned about his past, interacted with the world through text.11 In preparation for our conversations, he would arrange books, letters and newspaper articles, and he picked them up in turn as he talked, to underscore one point or another. In the echo chamber of the theories that he mastered as no other, he had found his vital element. Professor Jacob Taubes, a gifted reader in his own right who counted Gente among his disciples, attested in 1974 to Gente’s talent for ‘dealing intensively with unwieldy texts’.12 One of the peculiarities of the theory-obsessed ’68 generation is that hardly any theoreticians originated in their ranks. ‘As they silenced their fathers, they allowed their grandfathers to be heard again – preferably those who had been exiled’,13 the cultural journalist Henning Ritter wrote. Was he thinking of Peter Gente, who had served alongside him as a student assistant to Taubes in the 1960s? From that perspective, Gente was the ideal New Leftist: a partisan of the class struggle mining the archives.14

Gente travelled to Paris and brought back texts by Roland Barthes and Lucien Goldmann, authors no one knew in Berlin. Towards the end of the sixties, when the leftist book market began booming, he picked up odd editorial jobs. But he didn’t find his life’s theme until, in his mid-thirties, he decided to start his own business: in 1970, he and some friends and comrades founded the publishing company Merve Verlag. Initially, they called themselves a socialist collective. As their political beliefs evolved, however, the organization of their work changed as well. For two decades, Merve shaped the theory scene of West Berlin and West Germany. From the student movement’s latecomers to the avant-garde of the art world, everyone got their share of dangerous thinking: Italian Marxism, French post-structuralism, a dash of Carl Schmitt, topped off with Luhmann’s sober systems theory.

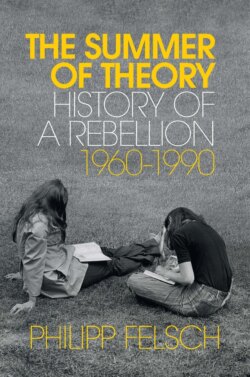

2 Heidi Paris and Peter Gente, West Berlin, around 1980.

But Merve probably never would have been anything more than just a minuscule leftist publisher whose products occasionally turn up in Red second-hand bookshops if Gente hadn’t met Heidi Paris. In the masculine world of theory, where women were all too often reduced to the roles of mothers or muses, she was a pioneer.15 She led the group’s publishing policy in new directions, contributing to the dissolution of the collective. From 1975 on, she was Gente’s partner both in work and in a personal relationship. The couple composed Merve’s legendary long-sellers, established authors such as Deleuze and Baudrillard in Germany, and steered their publishing house into the art world, where it has its habitat today. They produced books that didn’t want to be read at university; they transformed readers into fans, and authors into philosophical fashion icons. They worked on film projects with Blixa Bargeld and Heiner Müller; they did the rounds of the Schöneberg clubs with Martin Kippenberger.16 As well-entrenched members of the theory crowd, they coexisted with a like-minded milieu whose centre of gravity was the university, but whose orbit passed through Berlin’s smart night spots. Or vice versa. In the 1980s, the Merve paperbacks were required reading in this milieu.

‘We are almost never in Paris and are happy living in Berlin’, Heidi Paris and Peter Gente wrote in 1981 to the New York professor Sylvère Lotringer.17 West Berlin was an ideal location for the publishers. Speculative thinking flourished in the city’s exceptional political conditions. The Merve culture grew lavishly between the bars and discos of Schöneberg and the lecture halls of Dahlem. Berlin in the sixties had been a bastion of the New Left; in the seventies, it became a biotope of the counter-culture. And in the eighties, as the Cold War ideologues faded to spectres, postmodernism dawned. Hegel himself had held the Prussian capital to be the home of the World Spirit; his critical heirs thought it nothing less – although the existence of the ‘enclave on the front lines’, as Heidi Paris once called her city, actually seemed to contradict Hegel’s theory.18

The history of the publishing couple of Gente and Paris is inseparably connected with West Berlin, yet it is more than an intellectual milieu study of the city. People in Germany tend to equate the heyday of theory with what was known as ‘Suhrkamp culture’: the phrase was coined in 1973 by the English critic George Steiner, referring to the catalogue of the Frankfurt publishing house Suhrkamp as the canon of West Germany.19 And, in fact, Suhrkamp played a crucial part in shaping and propagating the genre, as we shall see. Their policy of producing theory in paperback was one thing that made a project such as Merve possible in the first place. But because the Berlin publishers never blossomed out into a company with employees, proper bookkeeping and the imperative of profitability, the files I discovered in Karlsruhe afford a different perspective: they recount the long summer of theory from a user’s point of view. All their lives, the Merve publishers and their friends identified themselves as avid readers. Accordingly, Merve was not just a publisher, but a reading group, a fan club – a reception context.

That fact is an invaluable advantage for my project of writing the history of a genre: to understand the success of theory since the sixties, examining how it was read and used is at least as important as its content20 – which has long since been studied in any case – as the recently published memoirs of some former theory readers have pointed out.21 Perhaps certain texts had a power of suggestion that was even greater than their systematic argument. This preliminary intuition, and the methodological choice which follows from it, are not aimed at adding yet another interpretation to the history of twentieth-century philosophy.22 This book recounts the formative experiences of Peter Gente, the odyssey of the Merve collective, and the discoveries of Gente and Paris. It follows the course of their readings, their discussions and their favourite books – but it does not seek to penetrate the grey contents of those texts. The history of science has long had its eye on ‘theoretical practice’, to use the Merve author Louis Althusser’s term for the business of thinking. Following him and others, that history has learned to pay attention to the media, institutions and practices of knowledge.23 Why should this approach not prove fruitful for the theory landscape of the sixties and seventies, the environment in which it was originally formulated?24 In 1978, Michel Foucault developed the concept of philosophical reporting – ‘le reportage d’idées’, a form devoted to the real history of thought. ‘The world of today is crawling with ideas’, he wrote, ‘that are born, move around, disappear or reappear, shaking up people and things.’ Hence, there is always a need ‘to connect the analysis of what we think with the analysis of what happens’.25 This book’s purpose is precisely that.