Читать книгу The Summer of Theory - Philipp Felsch - Страница 22

Paperback Theory

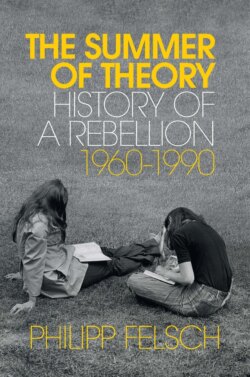

ОглавлениеJacob Taubes also plays an important part in the history of theory in West Germany as one of the architects of the Suhrkamp culture. In 1965, when Gente arrived in his department, Taubes was in the middle of planning a new paperback series for the head of Suhrkamp, Siegfried Unseld. Three years before, Unseld had inaugurated the edition suhrkamp, a rainbow-coloured shelf of paperbacks that became the emblem of an intellectual era. The concept of supplying literary and philosophical titles in a pocket format had become feasible only after the death of Unseld’s predecessor Peter Suhrkamp, who had staunchly refused to deal in paperbacks.39 In 1962, Unseld’s innovation was still the object of controversy at the publishing house. Among the questions debated by his advisors, who included the paperback critic Enzensberger, was whether an ‘intellectual series’ could afford to have bright-coloured covers. The compromise initially adopted – printing Willy Fleckhaus’s cover design on a dust jacket which could be removed to reveal grey cardboard as a guarantee of intellectual solidity – says a great deal about the weight of the ideological confrontation. The edition suhrkamp sold well from the beginning; the philosophical titles in particular seemed to appeal to the ‘younger and student readers’, Unseld’s target audience for the new series.40 Authors such as Wittgenstein, Bloch and Adorno topping the sales statistics even in train-station bookshops was remarkable news.41 Husserl’s Logical Investigations, a fundamental text of modern philosophy, had sold just 7,500 copies by 1966. The long-term best-seller of the twentieth century, Heidegger’s Being and Time, had sold 40,000 copies.42 Figures like these were low compared with Suhrkamp’s philosophical paperbacks: Herbert Marcuse’s Culture and Society, which appeared in edition suhrkamp in 1965 as Kultur und Gesellschaft, sold 80,000 copies within a few years.43

At first, the critics of the paperback format saw its success as confirmation of their suspicions that people might buy paperbacks, but not read them.44 But the phenomenon also admitted the opposite interpretation: perhaps the affordable books were actually revolutionizing people’s reading habits; perhaps they were a medium for disseminating difficult ideas. Unseld, one of the optimists, commissioned the young luminaries of the West German social sciences to conceive another series that would serve this purpose. Jürgen Habermas, Hans Blumenberg, Dieter Henrich and Jacob Taubes were engaged as advisors and series editors to attune Suhrkamp’s academic catalogue to the zeitgeist. A few years later, Unseld added Niklas Luhmann to this circle. ‘The individual books should be formally appealing as well as inexpensive’, the editor Karl Markus Michel wrote to the professors in January of 1965, ‘and should be distinct both from the ubiquitous pocket books and paperbacks and from those traditional books that tend to crawl away and hide on bookshop shelves.’45 The result, presented the following year at the Frankfurt Book Fair, was the Theorie series, whose minimalistic cover was the sober counterpoint to the candy-coloured, pop-art design of its older sister: the Suhrkamp culture’s White Album, so to speak, to follow its Sergeant Pepper.46 Of course, the Theorie series never became as successful as the edition suhrkamp. Not until the 1970s did its successor series reach a wider readership, the midnight-blue suhrkamp taschenbuch wissenschaft (that is, ‘Suhrkamp academic paperback’, or stw for short).47 The Theorie series can be credited with a different achievement, however: its title helped to establish a new genre.