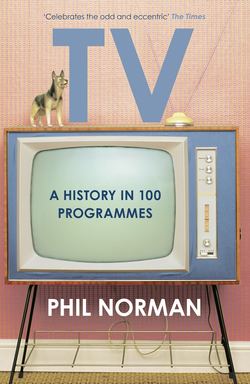

Читать книгу A History of Television in 100 Programmes - Steve Berry, Phil Norman - Страница 25

THE SUNDAY-NIGHT PLAY: A SUITABLE CASE FOR TREATMENT (1962) BBC Drama drops out.

ОглавлениеDear David Mercer, can you please explain why all your plays are about David Mercer?

A student writes to David Mercer, c. 1972

IN CINEMA, THE HIERARCHY was always plain. Stars first, then director, and bringing up the rear, if they’re even mentioned at all, the writer. In the 1960s, television – smaller, more flexible and less glamorous – had a more variable pecking order. Thanks to ever-closer ties with the theatrical revolution, the writer could occasionally, and not always reluctantly, become the star of their own show.

David Mercer was one of many post-war playwrights who had risen from the provincial working class through state and self-education. Born into a Wakefield mining family, he spent four years with the Navy before moving to Paris to work as first a struggling painter, then a struggling novelist. Realising the ‘abstract cul-de-sac’103 he’d backed himself into, he turned to drama, specifically the drama of his own experience. His first play, Where the Difference Begins, was intended for the stage but found a home on the BBC. It dealt with the culture gap between a working class artist and his suspicious kinfolk in an honest and very straightforward way. Mercer would later describe it as ‘one of the dreariest plays ever written by me, or anyone else, for that matter.’104 He seemed to be cultivating an oeuvre every bit as unforgiving as his resting expression of intense concern.

Then, in 1962, the usually methodical Mercer made a breakthrough, written ‘in an absolute kind of trance for three weeks’.105 When director Don Taylor, Mercer’s main early creative collaborator, asked about it, he found his colleague’s usual intense frown replaced by ‘a large, round-faced Yorkshire grin’.106 A Suitable Case for Treatment left the old straight track of social realism and hiked off into the unknown.

Morgan Delt, disillusioned thirtysomething man for whom ‘life became baffling as soon as it became comprehensible’, is in the process of being divorced from his wife Leonie. He sleeps in his car and spends his days railing against society like an Angry Brigade Hamlet, or palling around with Guy the Gorilla at London Zoo. Otherwise he keeps himself occupied by pestering his ex-wife, pinning offensive posters in her flat, shaving a hammer and sickle into her poodle’s back, hanging her stuffed toys on a small portable gallows and blowing up her mother. A few years before the screen would fill with them, Morgan was its first drop-out hero.

Appropriately, the play didn’t conform to the standard two act shape. Scenes fragmented and were interrupted by clips of films from Battleship Potemkin to Tarzan. Dream sequences were not the usual gauzy, slow motion affairs but stark skits in a black limbo with Morgan’s mum in secret police uniform. Don Taylor somehow crammed it all into an hour – a pre-recorded and edited hour, the thing being far too complex to transmit live, as most drama still was.

These technical innovations would have meant nothing without Mercer’s increasingly sharp dialogue. Morgan’s cockney Trot mum, played to the hilt by Anna Wing, had some beautifully turned lines worthy of Hancock: ‘Your dad wanted to shoot the royal family, abolish marriage and put everybody who’d been to public school in a chain gang. He was an idealist, was your dad.’ But the main event was Ian Hendry’s Morgan, manic in all emotional directions. ‘I’m a bad son,’ he mused. ‘Is it the chromosomes, or is it England?’ He castigated Leonie’s suave new suitor, saying, ‘He slid into our lives like a boa constrictor. You’ve never seen him with her – he undulates. Turned my back one day and he gulped her down like a rabbit.’

This unprecedented play left critics straining for parallels. The slapstick incursions and head-banging philosophy put many critics in mind of Spike Milligan. ‘Like Milligan, Morgan Delt was either a thousand years ahead of his time or, more likely, probably an essential antidote for his time,’ judged Derek Hill, approving what was ‘less a play than a welcome disturbance of the peace.’107 Michael Overton applauded what he saw as a long overdue BBC response to the dominance of Armchair Theatre. ‘The BBC has been steadily playing safe and countering ABC-TV’s adventurousness with dull doldrum plays unimaginatively directed and indifferently acted. David Mercer’s play must have shaken the antimacassars in the most staid middle-class homes, and made the majority switch straight back to Sunday Night at the London Palladium.’108

Scheduled after Mercer was a repeat of Anthony Newley’s The Johnny Darling Show, a pseudo-sequel to Gurney Slade in which the eponymous teen idol senses the end of the world and embarks on a philosophical fantasy journey of social and spiritual Armageddon, with songs by Leslie Bricusse. For some viewers, a whole evening of visual experiment and existential despair was too much, and in the following edition of Points of View many antimacassars were shaken at the Beeb, and Mercer especially.

Mercer’s protagonists were not so much off the beaten track as frolicking in the tall grass several fields away: a young man who takes an axe to a middle-class Sunday tea party; a leather-clad septuagenarian vicar biker; a childlike pair of zookeepers who fill a disused swimming pool with inflatable animals and trapezes. ‘Mercer is not just a nonconformist,’ reckoned Don Taylor, ‘he is a nonconformist nonconformist, for whom a beard and a guitar are as square as a dark suit and rolled umbrella. He is his own strange self.’109 A Suitable Case … became a film, Morgan!, in 1966, adapted by Mercer but sweetened, he felt, too much by director Karel Reisz into a poppy tale of swinging outsiderism. ‘Dropping out’ was now a cultural buzzword, on its way to becoming a mini-industry. Only conformist nonconformists need apply.

For a confirmed outsider, Mercer was gregarious to a fault. Joan Bakewell recalls the ‘hotbed of neo-Marxism’110 he presided over in Maida Vale, where she would dash after presenting Late Night Line-Up to hobnob with Pinter, Kenneth Tynan and company. He was the most visible of the new TV playwrights, interviewed by everyone from Melvyn Bragg to David Coleman. His goatee and polo neck became familiar enough for Michael Palin to impersonate him on Monty Python, chain-smoking behind a typewriter, captioned simply: ‘A Very Good Playwright’.

Mercer’s TV output declined in the seventies. Despite quirky successes like the half-hour Me and You and Him – a triumph of videotape editing in which three Peter Vaughans conduct a psychiatric slanging match – his style was sidelined in the push toward naturalism. Even the introduction of high-definition colour seemed set against him. In 1972’s The Bankrupt, a crisis-hit Joss Ackland experiences the same kind of black limbo dreams as Morgan Delt, though where the original monochrome abyss sold the hallucination, the colour camera merely highlighted what Kenneth Tynan once dismissed as ‘the platitudinous void, with its single message: “Background of evil, get it?”’111

And anyway, argued critics, TV had moved on from this sort of experimental tinkering, hadn’t it? ‘I’m afraid this kind of crossword-puzzle drama may find a place in the so-called “intellectual” theatre,’ opined John Russell Taylor, ‘but it cannot make much sense to the average television viewer.’112 Clive James thought The Bankrupt showed a writer losing his way: ‘Mercer, like John Hopkins, is likely to eke out a half-imagined idea by double-crossing his own talent and piling on precisely the undergrad-type tricksiness his sense of realism exists to discredit.’113

Mercer died in 1980, firmly out of step with the timid TV mainstream, which duly gave him a retrospective but otherwise continued to be suspicious of the risky and remarkable. Mercer set the template for the bold, confessional playwright who was as at home appearing on television as writing for it. His more concrete, if less eye-catching, quality was noted by Mervyn Johns: ‘A television writer who cares, and is encouraged to care, about words is a rarity; without Mercer’s example, that rarity may become an extinct species.’114