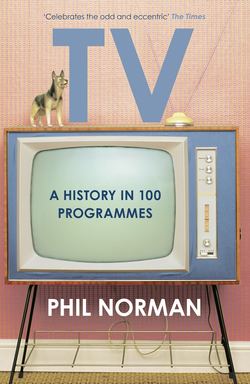

Читать книгу A History of Television in 100 Programmes - Steve Berry, Phil Norman - Страница 27

WORLD IN ACTION (1963–98) ITV (Granada) Current affairs go commando.

ОглавлениеIN 1963 CURRENT AFFAIRS reached critical mass. In the summer, Britain’s press enjoyed unprecedented levels of political influence when they published the indiscretions of John Profumo. The shaming of a British minister was followed by the death of a US President. For four days in November, from the first, breathless, interruption of an episode of soap opera As the World Turns, through the assassination of Oswald and the state funeral on the twenty-fifth, the USA turned to television for information and support, specifically to Walter Cronkite of CBS News. A programme that combined the fearlessness of an investigative tabloid with television’s immediate visual impact had to be made, and it was.

The current affairs feature began with BBC’s Special Enquiry in 1952 and, the following year, its flagship Panorama. ITV returned volley with This Week and Searchlight. The latter, edited by Australian ex-tabloid editor Tim Hewat, caused such regular controversy it devoted one edition to scrutinising itself. When the Television Act finally caught up with Searchlight’s insufficient impartiality, Hewat reassigned his men the banner of World in Action, a ‘Northern Panorama’ that would fundamentally change the look of TV documentary.

Hewat created World in Action to cover a single subject each week. On-screen reporters were replaced by voice-overs including that of James Burke, leaving the screen filled with the matter in hand. The matter was often visualised with shamelessly unsubtle tabloid stunts, such as staging a mass funeral in a Salford street to introduce a report on bronchitis. These were organised by the show’s team of fixers, who also arranged everything from foreign currency to access to closed borders. Tactics like this helped World in Action’s audience rise to twice Panorama’s.117

World in Action also introduced the 16mm film camera. Several times less bulky than the usual 35mm Arriflex, the smaller gauge apparatus cut the size of a location crew from twelve to six, giving the team greater manoeuvrability. Where before events were brought in front of the camera, now the camera could dive straight into the situation. The consequent grainy smutch of those early guerilla reports was a badge of honour; Hewat upbraided one fastidious producer’s suspiciously immaculate African footage as a screen full of ‘bloody back-lit begging bowls!’118

When a huge story broke at an inconsiderately late point in the week, the leaner team could put an emergency programme together in under three days. All-nighters pulled to cover breaking scoops like the collapse of the John Bloom business empire were celebrated in hard-bitten Fleet Street tones. ‘We have to do a week’s work in two days. It’s impossible, but sometimes it gets done,’ editor Alex Valentine told TV Times, adding wistfully, ‘I’ve never seen so many dawns in my life, I don’t mind telling you.’119

Tabloid clichés in the publicity material were fine. Tabloid clichés in the content were signs of slackness. As the same subjects came round again each season, the show’s style atrophied. Anything that worked, like the Salford stunt, was recycled when time and inspiration went. ‘World in Action is sometimes in danger of becoming a victim of its own form,’ wrote Peter Hillmore, lamenting its use of picture postcard scene setting – canals to introduce Amsterdam, or a politician’s view preceded by the Houses of Parliament from the Thames. ‘I know the team has to fill thirty minutes with film, but it doesn’t always have to look so desperate about it.’120

When all parts of the World in Action team pulled together, the results were unbeatable. Its many torture investigations of the early 1970s brought horrific news of every regime’s actions from Zanzibar to Turkey to Ulster. It risked a great deal more than its reputation to demonstrate how simple it was to smuggle car parts into sanctioned Rhodesia, and arms to war-torn Biafra. It pioneered mass election debate with ‘The Granada 500’, a panel of pundits bussed in from bellwether constituency Preston East to grill the party leaders. The edition with perhaps the greatest impact, ‘The Rise and Fall of John Poulson’, didn’t unearth much in the way of new material on the corrupt property developer, but did set out the available evidence in a clearer way than anyone had managed before, laying bare the dense web of connections. The film was still incendiary enough to be temporarily blocked by the IBA, which led to accusations of a conflict of interest among ITV grandees – T. Dan Smith, one of the main accused, had been until very recently a director of Tyne Tees Television. (Later, while in jail for corruption, Smith encouraged fellow inmate Leslie Grantham to take up professional acting, and a future star of EastEnders was born.)121

Occasionally the programme went too far. Covering anti-Sony factory protests in 1977, its team hunted America to film the rumoured gatherings of people in T-shirts claiming, ‘Sony – from the people who gave you Pearl Harbor’. Not finding any such shirts, they printed a few off themselves.122 ‘Born Losers’, shown in 1967, was a compassionate study of a nine-child family living on £16 a week; it got its message across to many viewers, but broadcasting the Walshes’ intimate details came close to destroying the family itself.123 From then the team were wary of putting members of the public quite so brazenly on show – a consideration regarded as optional by other programmes.

The emergent youth culture demanded coverage. Young producer John Birt’s idea of helicoptering Mick Jagger into the grounds of a stately home to chat with the Bishop of Woolwich was a success, in publicity terms at least. (‘We should aim to transmit at least one outrageous and improbable programme each year,’ demanded long-serving editor Ray Fitzwalter.124) But most youth culture stories, from the Mod revival to acid house, tended towards prudishness. ‘No speed party is complete without a joint of grass,’ vouchsafed the authoritatively prurient narrator of Haight-Ashbury examination, ‘Alas, Poor Hippies, Love is Dead’.

News technology progressed apace. Through the late 1970s, the old film crews were steadily replaced by ‘creepy-peepies’: lightweight video cameras far more convenient even than 16mm. A generation of cameramen were left feeling, in the words of one ACTT member, ‘like wheeltappers at a hovercraft rally’.125 Even the BBC’s Panorama started to catch up with the times: a 1981 documentary on German rocket makers OTRAG used a blizzard of electronic effects to enliven the presentation of its great mountain of paper evidence. ‘The days of pointing a camera at a newspaper cutting are threatened at last,’ predicted Peter Fiddick. ‘If you can’t read it, they’ll flash it, colour it and creep it across the screen … until you’re blinded into literacy.’126 The Richard Dimbleby generation of current affairs gave way to Hewat’s boys across the board.

World in Action wasn’t killed off by IBA ruling or legal challenge, but a soap opera. In 1994 EastEnders went thrice-weekly, ruining ITV’s Monday night. The 1990 Broadcasting Act had already loosened the third channel’s current affairs commitments. World in Action, now reaching as little as five million viewers,127 was promptly shifted up against the soap as a sacrifice. It lasted a little over three years. Granada won the bid to replace its old show: ‘Whether by performance, image, heritage or perception, all agree on the value of World in Action,’128 it admitted in the tender, but ‘we need to make current affairs less threatening to younger viewers.’ Its solution, based on CBS’s 60 Minutes model, became Tonight with Trevor McDonald. Broadsheet pundits began making merry with the freshly imported phrase ‘dumbing down’.