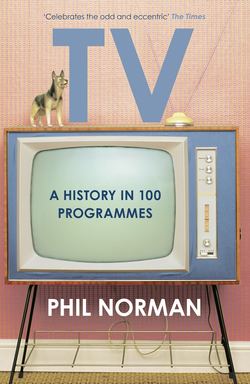

Читать книгу A History of Television in 100 Programmes - Steve Berry, Phil Norman - Страница 21

ARMCHAIR THEATRE: A NIGHT OUT (1960) ITV (ABC) The theatrical revolution reaches the front room.

ОглавлениеI’ve read your bloody play and I haven’t had a wink of sleep for four nights. Well, I suppose we’d better do it.

Peter Willes commissions Harold Pinter’s The Birthday Party for Associated-Rediffusion, 195972

LEGEND HAS IT THAT John Osborne’s Look Back in Anger transformed British theatre overnight from a staid world of French window farces and solemn verse epics into a fiercely committed force for social change. It didn’t quite do that, but it did perform one useful service: getting the under-thirties into the stalls. This demographic shift was helped by the transmission of one of the play’s cleaner passages as a BBC television ‘Theatre Flash’, alerting the chattering youth to the presence of something other than genteel matinees for scone-munching Aunt Ednas. A long and fruitful alliance between TV and the modern stage was born.

Another TV beneficiary was The Birthday Party, a drama of nameless persecution in a south coast bed and breakfast, written by jobbing actor Harold Pinter during a 1957 tour of Doctor in the House. Disastrous notices on its London debut threatened it with early closure until the Sunday Times praised it to the skies, but it took a production directed by Joan Kemp-Welch on peak-time ITV for it to reach ten million viewers. Many viewers took against its obscurity (‘We are still wondering what it was all about and why we didn’t switch it off’).73 Others had their eyes opened to ‘a Picasso in words’, something new and wonderfully different from the usual tea-table crosstalk. While many found it disturbing, one viewer reported ‘loving every word … of the author’s uproarious nonsense’.74 After transmission, the ever-helpful press department of the Tyne-Tees region became so overwhelmed by inquiries it issued a fact-sheet offering a ‘reasonable and interesting interpretation’ of the play. Existential drama had joined the mainstream.

ITV’s main dramatic showcase at the time was Armchair Theatre. Initially a ragbag of classics and light comedies, it was remoulded by incoming Canadian producer Sydney Newman in 1958 to reflect the new theatrical mood of contemporary social engagement. (Newman’s archetypal idea of an armchair play involved a small-time grocer threatened by a new supermarket.)75 Many new writing talents would be discovered or nurtured by Newman, and Pinter joined their ranks on 24 April 1960 with his first original television work, A Night Out.

The nocturnal jaunt is made by diffident office worker Albert Stokes (Tom Bell) escaping from the home of his pathetically possessive widowed mother. The works do he attends ends in disaster when he’s mischievously accused of groping a secretary. He flees, ending up in a deeply uncomfortable encounter with a hooker (Pinter’s then wife, Vivien Merchant), who affects a cartoon poshness. (‘You’ve not got any cigarettes on you? I’m very fond of a smoke. After dinner with a glass of wine. Or before dinner … with sherry.’) They almost start to bond over their shared tragic isolation, but when she asks him too many questions, in a manner too like his own mum, Stokes spectacularly falls apart. With nothing in his social armoury between taciturn gaucheness and inarticulate rage, Stokes proves himself completely incapable of starting a life outside the suffocating maternal evenings of gin rummy and shepherd’s pie: not so much Angry Young Man as Awkward Old Boy. Osborne’s threatened men ranted with theatrical garrulousness. More appropriately for the small screen, Pinter’s Stokes agonises in silent close-up.

The mysterious, spectral characters that were Pinter’s trademark were perhaps unsuited to Armchair Theatre’s bread-’n’-scrape naturalism. (Stokes certainly shows none of the buried redeeming features a social realist anti-hero usually possesses.) But his sheepishly combative dialogue fitted perfectly with Newman’s mission statement, sketching a repressed lower-middle-class claustrophobia heightened by director Philip Saville’s endlessly burrowing cameras. For extra realism, the coffee stall where Stokes meets his workmates was John Johnson’s famous all-night concession, normally found outside the Old Vic but shifted to the studio for the occasion.76

Though it wasn’t Pinter’s greatest work, A Night Out was a solid hit, reaching 6.38 million. Three days after it aired, Pinter joined the theatrical aristocracy as The Caretaker opened to prodigious acclaim, but he calculated that the play would have to run at the Duchess Theatre until 1990 to get the exposure A Night Out caught in one go.77 As well as plays, Pinter’s subsequent TV work spanned everything from The Dick Emery Show to Pinter People, a collection of sketches animated by Sesame Street alumnus Gerald Potterton. This was for the psychedelic series NBC Experiment in Television, which gave US network time over to the imaginations of everyone from Tom Stoppard to Jim Henson.

By the end of 1960 the all-purpose avant-garde TV play had become such a part of the broadcasting landscape it was ripe for parody. The writer hero of Joan Morgan’s Square Dance toiled away at a modishly obscure drama called Ending’s No End, featuring a Greek chorus of Teddy boys and the cast turning radioactive in the final act.78 The joke relied on every viewer having at one time switched off something by Pinter or his contemporaries in confusion and disgust. What it ignored was the significant portion who kept watching.