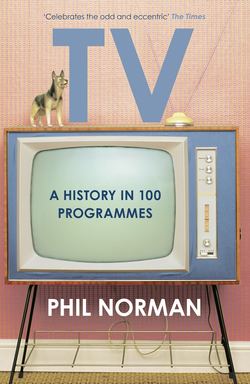

Читать книгу A History of Television in 100 Programmes - Steve Berry, Phil Norman - Страница 8

CAVALCADE OF STARS (1949–52) DuMont (Drugstore Television) Vaudeville begets the sitcom.

ОглавлениеAS TELEVISION PROGRESSED FROM esoteric technology to worldwide medium-in-waiting, one question dominated: what the hell are we going to put on it? The Manchester Guardian held a competition asking just that in 1934. Winning suggestions ranged from high mass at St Peter’s to a chimps’ tea party, ‘MPs trying to buy bananas after hours’, and ‘Mr Aldous Huxley enjoying something’.19

In America, such wild fancies became real. There was the 1944 show that led one critic to gush, ‘This removes all doubt as to television’s future. This is television.’20 ‘This’ was Missus Goes A-Shopping, a distant ancestor of Supermarket Sweep. A more solid solution to the content problem was sport. Entire evenings in the late 1940s consisted of the sports that were easiest to cover with the new stations’ primitive equipment: mainly boxing and wrestling. On the other hand, figured New York-based programmers, there was a whole breed of people who were past masters at filling an evening with entertainment off their own bat. They were just a few blocks away, doing six nights a week for peanuts.

Vaudeville stars like the Marx Brothers had dominated pre-war cinema comedy, touring a stage version of each film across America to polish every line and perfect every pratfall before they hit the studio. Television wanted vaudevillians for the opposite quality: bounteous spontaneity. The big, big shows began with NBC’s Texaco Star Theatre, hosted by Milton Berle. Through a mess of broad slapstick, elephantine cross-dressing and taboo-nudging ad libs, Berle became the first of television’s original stars, with his loud and hectic shtick penetrating the fog of the early TV screen like bawdy semaphore from the deck of an oncoming battleship. No marks for élan, but plenty for chutzpah.

Other broadcasters followed suit, including DuMont. The odd one out of the networks, DuMont originated from TV manufacturing rather than broadcast radio, so had to search harder to find celebrities, and struggled to keep them. Cavalcade of Stars, their Saturday night shebang, was a case in point. It was originally hosted by former Texaco stand-in Jack Carter, then Jerry Lester, both of whom were poached by NBC as they became popular. Desperation was setting in when they came to Jackie Gleason. Gleason, having bombed in Hollywood, was working through the purgatory of Newark’s club circuit when DuMont offered him a two-week test contract. Gleason had worked in TV before, starring in a lacklustre adaptation of barnstorming radio sitcom Life of Riley, so had his reasons to be wary. But that was someone else’s script. Cavalcade was 100% Jackie.

Every show needed a sponsor. Cavalcade, lacking the might to pull in big time petroleum funds, was sponsored by Whelan’s drugstore chain. Each edition was preceded by a strident, close-harmony paean to the delights of the corner pharmacy, under the bold caption ‘QUALITY DRUGS’. Then on came The Great One in imperial splendour with a retinue of his ‘personally-auditioned’ Glea Girls. Often he’d daintily sip from a coffee cup, roll his eyes and croon ‘Ah, how sweet it is!’, his public chuckling in the knowledge that the cup wasn’t holding coffee. After his opening monologue – a combination of double-takes, reactions and slow-burns as much as a string of verbal gags – he’d request ‘a little travellin’ music’ from his orchestra, and to the resulting snatch of middle eastern burlesque, he slunk around the stage in a possessed belly-cum-go-go dance before freezing stock still and uttering the immortal line, ‘And awaaaaay we goooo!’ After all that, the programme actually started.

This indulgently whimsical ceremony wasn’t unique to Cavalcade, but on Gleason’s watch it grew into a kind of baroque mass, initiating the audience into his comic realm. The logic of replicating the communal aspect of stage variety on such a private, domestic medium seems odd today, but a large proportion of Gleason’s working class audience, unable to afford their own TVs, watched en masse in the bars and taverns of the Union’s major cities (DuMont’s limited coverage never reached the small towns), creating their own mini-crowds who joined in with gusto. Vaudeville’s voodoo link with the audience could cross the country this way. Performer and punter were in cahoots.

Cavalcade wasn’t all Pavlovian faff. The main body of the show boasted as much meat as that of its star. Dance numbers and musical guests were interspersed with extended character sketches taken from life – Gleason’s life. At one end of his one-man cross-section of society was playboy Reggie Van Gleason III. At the other, Chaplinesque hobo The Poor Soul. Somewhere in between came serial odd job failure Fenwick Babbitt and The Bachelor, a pathos-laden mime act in which Gleason would prepare breakfast or dress for dinner with all the grace and finesse you’d expect from a long-term single man, to the melodious, mocking strains of ‘Somebody Loves Me’. Hobo aside, Gleason had lived them all.

Gleason’s fullest tribute to his Bushwick roots was the warring couple skit that became known as ‘The Honeymooners’. Gleason played Ralph Kramden, a short-fused temper bomb of the old-fashioned, spherical kind; a scheming bus driver with ideas beyond his terminus. He lived with his more grounded wife Alice in a cramped, walk-up apartment at 328 Chauncey Street, a genuine former address of Gleason’s and possibly the most accurate recreation of breadline accommodation in TV comedy. In this washboard-in-the-sink, holler-up-the-fire-escape poverty, Kramden and his unassuming sewage worker neighbour Ed Norton (Art Carney) sparred, plotted and generally goofed around. The working-class- boy-made-good was talking directly to his peers about life as they knew it, as surely as if they were sat at the same bar. The aristocracy of executives and sponsors that made it technically possible didn’t figure in the exchange at all. They delivered the star, and then made themselves scarce until the first commercial break. It would be television comedy’s struggle to preserve this desirable set-up against tide after tide of neurotic, censorious meddling from above.

Cavalcade of Stars became DuMont’s biggest show. Naturally, this meant Gleason was snapped up by CBS within two years. His fame doubled, and that of ‘The Honeymooners’ trebled. It broke out to become a sitcom in its own right, but oddly never achieved quite the same level of success outside its variety habitat. Meanwhile Sid Caesar, Imogene Coca and a stable of future comedy writing titans seized the vaudeville crown with NBC’s Your Show of Shows.

Gleason himself wasn’t immune to the odd misstep. In 1961 he hosted the high-concept panel game You’re in the Picture, in which stars stuck their heads through holes in paintings and tried to determine what they depicted. The première bombed so hard that week two consisted entirely of Gleason, in a bare studio with trusty coffee cup to hand, apologising profusely for the previous week. He was reckless, chaotic and hopelessly self-indulgent, but he instinctively knew when he’d failed to entertain. He was also relentlessly determined, signing off his marathon mea culpa with a forthright, ‘I don’t know what we’ll do, but I’ll be back.’ Television couldn’t wish for a better motto.