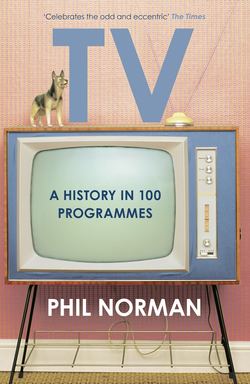

Читать книгу A History of Television in 100 Programmes - Steve Berry, Phil Norman - Страница 20

THE STRANGE WORLD OF GURNEY SLADE (1960) ITV (ATV) The sitcom eats itself.

ОглавлениеWho and what is Anthony Newley?… This brown-haired, blue-eyed searcher after truth hovers and flits in and around and above the world of show business like a creative helicopter.

Radio Times, 9 November 1961

THOUGH IT STILL HANDLED rock ’n’ roll with all the aplomb of Stan Laurel taming a cobra, television did as much as cinema and radio combined to bring big, brash all-round American entertainment to the chilly front rooms of ration-squeezed Britain. The size, confidence and polish of those variety showcases were swiftly imitated by home-grown entertainers who got their suits reupholstered, their smiles re-pointed and their accents suspended somewhere between New England and the Old Kent Road. The alien sheen of these imitation Yanks – the brittle charm of Brucie, the oily palms of Michael Miles, the messianic humility of Hughie Green – caused amusement and unease among viewers accustomed to the polite cough and the if-you-please of English stage tradition.

Comic and singer Anthony Newley, from out of the Hackney Marshes via the Italia Conti stage school, acknowledged the incongruity of the transatlantic manner. He developed a penchant for running a self-deprecating commentary on his own act. On a UK tour to promote his film Idol on Parade, he stood by the screen as the opening credits rolled, talking them down, one by one. (‘“Directed?” The director couldn’t direct traffic! “Photographed by?” He nipped out to Boots the chemist …’64) Television, the most self-referential medium yet hatched, snapped him up.

Newley’s TV accomplices were writers Sid Green and Dick Hills, who had constructed specials for Sid James, Roy Castle and, disastrously, Eamonn Andrews. Initially billing themselves as the grand ‘SC Green and RM Hills’, they soon relaxed into ‘Sid and Dick’, names more appropriate to their modern, laid-back writing style. ‘They admit cheerfully that they belong with the coffee shop and back-of-the-envelope script writers,’ reported the Mail, ‘rather than the agonised pacers around kidney-shaped desks in grey flanelled rooms.’65

Newley’s attitude to comedy writing was similarly easygoing. ‘How do I define humour?’ he pondered at the behest of the TV Times. ‘I don’t. I wouldn’t dare.’66 After two reasonably successful Saturday Spectaculars for Lew Grade’s ATV in early 1960 – one featuring copious amounts of Peter Sellers – Newley, Hills and Green tackled the still maturing world of the sitcom, applying their skills in the same sideways-on manner. Given carte blanche to fill six half-hours how they fancied, they wrote, designed and shot the whole series in seven weeks. Newley was keen to point up the trio’s ground-breaking intent. ‘We hope to achieve humour without setting out to be deliberately funny.’67

An estimated twelve million viewers settled down at 8.35 p.m. on 22 October for the first episode of The Strange World of Gurney Slade. What they saw went roughly like this. We open on the front room of a terraced house, wherein Gurney Slade (Newley) is an unwilling participant in a Grove Family-style domestic soap with the feeblest acting and script known to man, all hurriedly-discharged paragraphs of backstory and leaden lines of chirpy banter. When the cue finally arrives for him to speak (‘Will you have an egg, Albert?’) he silently gets up, puts on his coat, moodily strutting past the floor manager and off the set, leaving the other actors mugging desperately. There’s even a cartoon sound effect as he smashes through the fourth wall.

The liberated Gurney wanders the streets aimlessly for the next twenty minutes. He despairs of the state of the medium. (‘“How’d you like your egg done, dear?” The Golden Years of British Entertainment! So much for Shakespeare and Sophocles.’) He reads minds. He chats to animals and the inanimate. He has conversations in invented languages. (‘Flangewick?’ ‘Clittervice!’ ‘Hendalcraw!’ ‘Mandelso!’) He frolics in the park with Una Stubbs and unsuccessfully tries to dump a vacuum cleaner. Finally, wearying of his constant presence on the television screen (‘I’m like a goldfish in a bowl. I’m a poor squirming squingle under a microscope!’) he begs the viewer to switch off the set and put him out of his misery.

The next few episodes were variations on the theme. Episode two in particular was a delightful romantic fantasy set on a disused airfield. Unfortunately it played out in front of an audience a good four million smaller than the opening show. ITV had a flop on their hands. Critics and punters, confused and bothered by this sullying of honest Saturday night fun with existential folderol, jeered as it all came crashing down. As one wag had it, ‘Is your Gurney really necessary?’68 Subsequent episodes were relegated to the depths of the night, where they could do less damage.

This turned out to be good timing, as things promptly became even stranger. Filmed well before the ratings nosedive, episode four swapped the bucolic exterior wanderings for the black-walled studio limbo of the avant-garde, presenting the trial of Gurney, before a Lewis Carroll kangaroo court, on the charge of having no sense of humour. (‘I did a television show recently and they didn’t think it was very funny.’)

The fitful attempts of Gurney to win over the hostile opinions of the eternally perplexed Average-Viewer family, a jury of cloth-capped everymen and a dead-eyed manufacturer of countersunk screws, went about as well as the real world defence of the series. ‘We have so much confidence in this progressive type of humour,’ insisted ATV, ‘that we are negotiating with Anthony Newley for another series in the new year. But not,’ they judiciously added, ‘necessarily Gurney Slade.’69

The sixth and final episode was further out still, being a formal deconstruction of the sitcom years before the concept made its academic debut. First a party of bowler-hatted bigwigs are shown the elements of a TV production, from cameras and microphones to The Performer (‘it goes through various motions which are calculated to entertain or amuse the viewers’). Then assorted incidental characters from previous episodes reappear, and round on Gurney for giving them inadequately detailed backgrounds, leaving them in a hazily-defined state of limbo after their moment on screen. Finally Anthony Newley appears as Anthony Newley, Gurney Slade grotesquely turns into a ventriloquist’s doll of himself, and Newley carries him off into the night.

At this point, the television sitcom was all of thirteen years old. When it was three, George Burns had given it the gift of self-consciousness. As it hit its teenage years, Newley granted it self-destruction. At the time it looked like just another odd little failed experiment; unlike A Show Called Fred, Gurney Slade had no Bernard Levin, no intellectual cheerleader, to trumpet its glory from the rooftops. It didn’t entirely lack a legacy, though: young Newley fan David Bowie was transfixed by the programme, and started swanning about the streets of Bromley in a Gurney-esque off-white mackintosh.70

Green and Hills moved into firmer show business territory, helping to resurrect the television fortunes of floundering double act Morecambe and Wise. Newley carried on his own meandering course, majoring in high concept musicals, but returning to television to guest on everything from the Miss World pageant to The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour. His later opinion of Gurney Slade was typically equivocal. ‘I think it proved something,’ he concluded, ‘even if I’m not sure what.’71