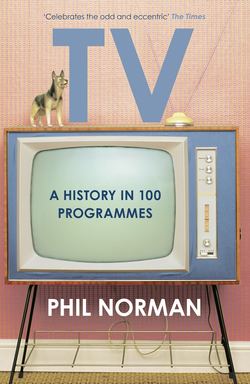

Читать книгу A History of Television in 100 Programmes - Steve Berry, Phil Norman - Страница 10

THE BURNS AND ALLEN SHOW (1950–8) CBS Still in its infancy, the sitcom goes postmodern.

ОглавлениеYou know, if you saw a plot like this on television you’d never believe it. But here it is happening in real life.

George Burns

THE COMEDIAN WILL ALWAYS beat the philosopher in a race – he’s the one who knows all the short cuts. In the case of postmodernism, that enigmatic doctrine of shifting symbols and authorless texts, the race was over before half the field reached the stadium.

George Burns and Gracie Allen were a dedicated vaudevillian couple. In 1929, the year before father of deconstruction Jacques Derrida was born, they were making short films that began by looking for the audience in cupboards and ended by admitting they’d run out of material too soon. While Roland Barthes was studying at the Sorbonne, Gracie Allen was enlisting the people of America to help look for her non-existent missing brother. A decade before John Cage’s notorious silent composition 4’33”, Gracie performed her Piano Concerto for Index Finger. And a few years after the word postmodernism first appeared in print, Burns and Allen were on America’s television screens embodying it.

The Burns and Allen Show began on CBS four years after the BBC inaugurated the sitcom with Pinwright’s Progress. In that time very little progress had been made. Performances were live and studio-bound. Gag followed gag followed some business with a hat, and the settings were drawing rooms straight from the funny papers. Burns and Allen’s set looked more like a technical cross section: the front doors of their house and that of neighbours the Mortons led into rooms visible from outside due to gaping holes in the brickwork. The fourth wall literally broken, George (and only George) could pop through the hole at will to confer with the audience. If anyone else left via the void they were swiftly reminded to use the front door. ‘You see,’ George explained to the viewers, ‘we’ve got to keep this believable.’

While Burns muttered asides from the edge of the stage, Allen stalked the set like a wide-eyed Wittgenstein, challenging anyone in her path to a fragmented war of words. From basic malapropisms to logical inversions some of the audience had to unpick on the bus going home, Gracie would innocently get everything wrong in exactly the right way. She sent her mother an empty envelope to cheer her up, on the grounds that ‘no news is good news’. She engaged hapless visitors in conversation with her own, unique, logic (‘Are you Mrs Burns?’ ‘Oh, yes. Mr Burns is much taller!’). Gracie was, admittedly, a Ditzy Woman, but this was the style in comedy at the time – Lucille Ball played a Ditzy Woman, and she co-owned the production company. Besides, Gracie’s vacuity could be perversely powerful – she was frequently the only one who seemed sure of herself. In her eyes she ranked with the great women of history (‘They laughed at Joan of Arc, but she went right ahead and built it!’).

While Gracie defied logic, George, in his mid-fifties but already the butt of endless old man gags, defied time and space. With a word and a gesture, he could halt the action and fill the audience in on the finer points of the story while Allen and company gamely froze like statues behind him. During Burns’s front-of-cloth confabs the viewer’s opinion was solicited, bets on the action were taken, and backstage reality elbowed its way up front. The story’s authorship was debated mid-show: ‘George S. Kaufman is responsible for tonight’s plot. I asked him to write it and he said no, so I had to do it.’ When a new actor was cast as Harry Morton, Burns introduced him on screen to Bea Benaderet (who played his wife Blanche), pronounced them man and wife, and the show carried on as usual. On another occasion, George broached the curtain to apologetically admit that the writers simply hadn’t come up with an ending for tonight’s programme, so goodnight folks.

Even the obligatory ‘word from the sponsor’ entered the fun. The show’s announcer was made a regular character: a TV announcer pathologically obsessed with Carnation Evaporated Milk, ‘the milk from contented cows’. These interludes, knocked out by an ad rep but fitting snugly within the framework provided by the show’s regular writers, exposed the strangeness of the integrated sponsor spot by embracing it. The show kept on top of the sponsor, and the sponsor became a star of the show – a very sophisticated symbiosis.

In October 1956, Burns gained a TV set which enabled him to watch the show – the one which, to him, was real life (the Burns and Allen played by Burns and Allen in The Burns and Allen Show were the stars of a show of their own, the content of which remained a mystery). He could sow mischief, retire to the set, and watch trouble unfold at his leisure. When he tired of that, he could switch channels and spy on Jack Benny. Burns’s fluctuating relationship to audience and plot (of which, he said, there was more than in a variety show, but less than in a wrestling match) was a deconstructionist triumph.

Ken Dodd questioned Freud’s theories of comedy, noting the great psychoanalyst ‘never had to play second house at the Glasgow Empire’. Burns and Allen, graduates of vaudeville, would have agreed. The self-awareness that high art lauds as sophisticated was part of the DNA of popular entertainment from the year dot – that is, about a day after George Burns was born.