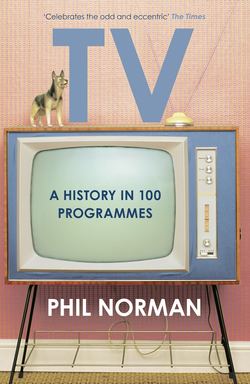

Читать книгу A History of Television in 100 Programmes - Steve Berry, Phil Norman - Страница 19

SIX-FIVE SPECIAL (1957–8) BBC TV’s first rock ’n’ roll smash hit.

ОглавлениеI knew we were in for some laughs when, at our first recording session, we were instructed to play out of tune because, in the words of Mr Good, ‘it doesn’t sound fascist enough’.

Benny Green recalls his tenure in Lord Rockingham’s XI, Daily Mirror, 27 January 1979

HERE’S AN INSTRUCTIVE EPISODE in the history of media hiring practice. Back in the mid-1950s when he undertook the BBC training course for junior producers, Jack Good made a bizarre mock advertisement as his graduation piece: a promotional spot for luxury coffins, which featured boxer Freddie Mills throwing Chelsea pensioners off the cliffs at Beachy Head.

Anyone exhibiting such jubilant bad taste these days (and allowing for the moral inflation of the last sixty years, its contemporary equivalent would have to be quite something) would be shown the door by the men from compliance. Instead, Good was given a free pass to create a sizeable chunk of youth TV, in the same casual manner. ‘These fat guys at the BBC said, “You look like a young chap, put something together with mountain climbing, fashion for girls, that sort of thing,”’ Good recalled. ‘I thought, I’ll put rock ’n’ roll on.’59

The Six-Five Special’s arrival was fortuitously timed. Not only did it coincide with Bill Haley’s first, epochal tour of the UK, it got first dibs on the brand new teatime slot. The 6-7 p.m. hour was previously a televisual dead zone by government decree, to allow parents to get younger children to bed, and older ones to do their homework. Into this oasis of orderly sobriety, Good brought unbridled anarchy.

‘This is basically a programme for young people,’ admitted the Radio Times, ‘but the term is relative. Rock ’n’ rolling grandmothers and washboard-playing grandfathers are welcome aboard the “Special”.’60 The Beeb intended rock ’n’ roll to be just one element of a varied magazine programme featuring sports coverage and other healthy outdoor activities, but Good knew the kids just wanted music.

For the first edition, conventional sets were built in Hammersmith’s Riverside Studios. Shortly before the live transmission, Good had the sets dismantled, leaving a bare studio in which guest stars, house band The Frantic Five and presenters Josephine Douglas and Pete Murray mingled informally with the audience of jiving teenagers. (‘A hundred cats are jumping here!’) The cameras lingered on the exuberant dancers as much as on the acts, and prizes were offered to couples who ‘cut the cutest capers’.

Square folks were aghast. ‘I feel thoroughly disgusted that the powers-that-be give time to exhibitions such as this. I cannot imagine that any decent-minded girl would permit herself to be pulled around in such a way, even to the extent of allowing herself to be thrown at times over the shoulders of the males taking part,’ fumed an outraged citizen of Penarth.61 Success was assured.

Early editions established the format, with Tommy Steele a regular draw. Ten shows in, shaggy-haired, surly ‘Six-Five Specialist’ Jim Dale arrived, graduating from warm-up man to main attraction. Uneasy with what he saw as the forced adulation the audience lavished upon him, he adopted a serious, unsmiling countenance as a defence mechanism. The twelve-million-strong audience, seeing their own youthful sullenness transformed by the cameras into cool belligerence, adored him even more, and television began following the movies in turning previously mortifying awkwardness into an alluring detachment.

Good soon became restless, feeling restricted by the ‘jolly, hearty’ element imposed on his programme (Freddie Mills’s ‘healthy activity’ spot was fine, but ramrod-backed guests such as Regimental Sergeant-Major Ron ‘Tibby’ Brittain quashed the groovy mood somewhat). The nugatory wage the BBC paid him didn’t help matters either. He upped sticks in 1958 for the more indulgent, independent pastures of ABC, the weekend-only independent broadcaster for the midlands and the north. ‘I want to bring a breath of excitement to television,’ he claimed in the publicity for Oh Boy!, ‘the fastest, most exciting show to hit TV’ which launched directly opposite the Special in June of that year.

Escaping the Beeb’s square tendency, Good made Oh Boy! about the music only – up to eighteen numbers in forty minutes with minimal fluff in between, accompanied by a wilder house band, Lord Rockingham’s XI. Thirteen weeks in, it was netting five million viewers, helped by hot footage of Cliff Richard that was condemned in the press. ‘His violent hip-swinging during an obvious attempt to copy Elvis Presley was revolting – hardly the kind of performance any parent could wish their children to witness,’ raged, of all institutions, the NME. ‘Remember, Tommy Steele became Britain’s teenage idol without resorting to this form of indecency.’62

Most of Oh Boy!’s viewers were poached from Six-Five. Good played up the inter-channel rivalry wherever he could, issuing dire warnings of industrial espionage: ‘Remember that spies are everywhere – ours as well as theirs – and a source of leakage will not remain hidden for long.’63 The Special rattled on without Good on the footplate, but the strain was beginning to show. A hasty September revamp went for all-out, show-stopping gigantism. A lavish new set – ‘the biggest in European TV’ – was built. Three new house bands were hired. Six female hosts – the ‘Six-Five Dates’ – shared presentation duties. Rock and skiffle were jettisoned in favour of beat music. It was all to no avail, and the Special’s journey ended on relatively desultory ratings of four and a half million.

Good’s innovations continued on the other side with Boy Meets Girls, featuring Marty Wilde and the sixteen Vernons Girls in a setting Good promised was ‘less frantic and less noisy than Oh Boy!’ The show’s main historical claim was the British debut of Gene Vincent, in a career doldrums after ‘Be-Bop-A-Lula’, whom Good remodelled in a leather-and-medallion rebel biker image, even, according to legend, egging him on to accentuate his motorbike injury with the off-stage exhortation, ‘Limp, you bugger, limp!’

When he tired of that, he went off in the opposite direction with Wham!, introducing ‘The Fat Noise’, a gargantuan house band which produced ‘the fattest, roundest sound that has ever come to television.’ But nothing was working, and Good departed for the USA, to finally hit real paydirt at the ABC network with Shindig! and set The Monkees on their path to self-destruction with the chaotic TV special 33 1/3 Revolutions Per Monkee.

Good returned to the UK sporadically throughout the next few decades, engineering various Oh Boy! revivals to put a spring in the step of middle-aged Teds, but he became increasingly estranged from contemporary pop with every slight return. Finally, in 1992, Jack Good left the music television business he’d been instrumental in creating, in as unexpected a way as he’d entered it – he joined a Carmelite hermitage in Texas.