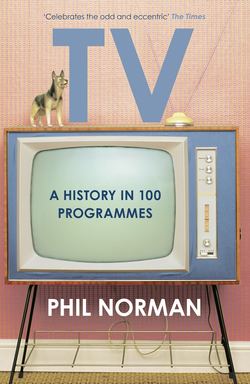

Читать книгу A History of Television in 100 Programmes - Steve Berry, Phil Norman - Страница 16

MY WILDEST DREAM (1956–7) ITV (Granada) The comedy panel show outstays its welcome

ОглавлениеA panel of celebrities, of one kind or another, are asked in turn to identify somebody they have met in the past. One of the particular eccentricities of television was shown up in this programme – the choosing of a ‘celebrity’ for the panel with no qualification or aptitude.

Review of Place the Face, Manchester Guardian, 9 July 1957

THE PANEL SHOW WAS a mainstay of television right from the beginning, for reasons both cultural and commercial. The cultural: since the nineteenth century the parlour game, a relaxed after-dinner orgy of banter and one-upmanship, was the icing on the middle class party cake, a civilised letting-down of the hair. The commercial: it’s cheap. It’s wit without a script, drama without a set, sport kept safely indoors. A prestigious panel show will have the country’s greatest two-dozen raconteurs fighting to appear on it. For a less prestigious one, a hundred dim bulbs will tear each other to pieces. Get the initial ingredients right, and it keeps itself afloat with minimal effort – it’s the perpetual motion format.

The cosy, chatty panel game established itself as a national comfort blanket on radio during the war. The BBC Home Service’s Brains Trust, in which clubbable eggheads like Kenneth Clark and Jacob Bronowski debated esoteric enquiries sent in by the public, reached nearly a third of Britons and made highbrows into stars. At the same time, the ease of it all bred suspicion. In 1942, questions were asked in the Commons on whether the Trust participants’ fees of £20 per session ‘for attempting to answer very simple questions’ was public money for old rope.44 It was certainly valuable old rope: in 1954, One Minute Please, predecessor to the long-running Just a Minute, became the first BBC panel format sold to the USA when Dumont bought the TV rights for $104,000.45

On television, two shows dominated. Vocational guessing game What’s My Line? began on CBS in 1950 and hit the BBC the following year, augmenting the elitist ‘wits’ enclave’ with a celebration of honest (but preferably amusingly odd) everyday work. In 1956 Princess Margaret attended an edition, watching from a special ‘royal box’ rigged up in the stalls. Then there was the loftier Animal, Vegetable, Mineral? This was an archaeological quiz that challenged academics to identify cuttlefish beaks and Tibetan prayer wheels, employed a young David Attenborough on its production team and invited viewers ‘to follow the fluctuating course of the contest as the experts grope towards the right solution, and perhaps enjoy a nice cosy feeling of superiority meanwhile.’46

Its star turn was archaeologist Sir Mortimer Wheeler, whose powers of observational deduction were second to none, though this wasn’t what made him such a draw. With a florid, expressive face, aided by an atavistic moustache made for twirling, he’d frown intensely at a flint axe or quern – hum, ha, squint, peer – then, in a cartoonish light bulb moment, all but leap in the air as the penny dropped. This showmanship was aided by the custom of lunching the panel, together with chairman Glyn Daniel, at a Kensington restaurant prior to live transmission. Occasionally, the team lunched too well: Daniel on one occasion lost complete track of the scores, decided nobody really cared anyway, and later, staring down the camera lens, used one of the objects – an Aboriginal charm – to put a hex on ‘the viewer who sent me a very silly letter.’47

This element of risk cast a long shadow over the format’s early days. Panel regular Gilbert Harding built a reputation for rudeness that frequently tipped over into outright disdain, such as his notorious claim to a What’s My Line? contestant that ‘I’m tired of looking at you.’ In 1954 the BBC, in a fit of panel game mania, commissioned several shows based on viewers’ ideas. Results included Change Partners, in which the panel had to sort eight married challengers into their constituent couples, working out who was shacking up with whom by asking them to recall marriage proposals, ruffle each others’ hair in an affectionate manner, etc. A year later they apologetically axed all their panel shows, except What’s My Line?48

ITV rushed in where the Beeb now feared to tread. In 1956 Granada converted an old BBC radio format into a prospective early evening panel hit. The panel took its cue from Does the Team Think?, Jimmy Edwards’s pastiche of The Brains Trust, which consisted of four comedians battling to out-gag and upstage each other. For My Wildest Dream the urbane Terry-Thomas led the panel, with his three ‘dreaming partners’ Tommy Trinder, David Nixon and Alfred Marks. Acting as ‘peacemaker’ was Kenneth MacLeod. It’s worth taking a close look at this particular programme, which handily features all the symptoms of lazy thinking, over-egged whimsy and misplaced trust in star power that marked out the format at its worst.

The panel’s objective was to determine, by diligent questioning, the secret fantasies of the humble folk wheeled before them. Inevitably, since most people’s fantasies tended towards the predictable (‘win the pools’, ‘go out with Marilyn Monroe’), a bit of creative bending of the rules crept in. Hence a woman appeared claiming she wanted more than anything to put a mouse in a guardsman’s boot, while another contestant longed to tickle a point duty policeman under the arms. Such bewildering dollops of ‘unbelievably fatuous’49 whimsy would, the producers hoped, be spun into comedy gold by the dreaming partners.

This turned out to be optimistic. What happened was that four comic minds, all too aware of the humourlessness of the situation, trod water ever more frantically until panic set in. One reviewer captured the mood of an early edition. ‘Last night there were intolerable bouts of shouting by all four of the panel and the chairman, and one at least of the challengers was made the butt of what could hardly be called humour. It did remain a little doubtful whether some of the quarrelling was genuine or faked because it seems to come to a peak each time before a break for advertisement.’50 Shouting, bullying, artifice: these vices would prove hard to suppress. My Wildest Dream was ‘not merely negatively silly but is positively revolting.’51 It started to appear later and later in the evening schedule, and the panel calmed down a bit, but the brickbats continued to the bitter end. (‘The most actively unpleasant panel show in commercial television.’52)

A second wave of panel shows in the seventies was more self-consciously refined. BBC2 games like Face the Music and Call My Bluff were all drawing room erudition and cravatted anecdote. Once again many entries were wireless in origin (in this case Radio 4), but the TV transfer brought certain behavioural tics to the fore. ‘On Face the Music,’ noted Clive James, ‘Bernard Levin takes a sip of water after getting the right answer. It is meant to look humble but screams conceit.’53 This extra level of gamesmanship was often in danger of edging the nominal subject of the programme out of the frame entirely.

The third wave began in the nineties with Have I Got News for You and its many derivatives, and this time it stuck. A few years’ craze became several decades’ industry. Where once strutted eccentrics who’d fallen into the role (Gilbert Harding, Nancy Spain, Lady Isobel Barnett), ‘panel show contestant’ was now a fully furnished vocation for comedians with the right voice, cultural references and agent representation. Precious little else had changed, though. In 2014, BBC Director of Television Danny Cohen tried to redress the archaic gender balance of the genre by outlawing all-male editions. Bow ties became polo shirts, but the panel show remained essentially a gentlemen’s club.