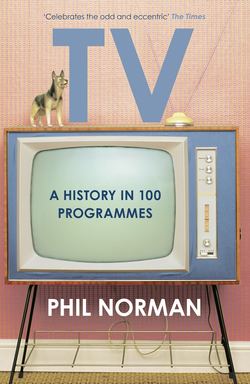

Читать книгу A History of Television in 100 Programmes - Steve Berry, Phil Norman - Страница 15

A SHOW CALLED FRED (1956) ITV (Associated-Rediffusion) Television comedy explodes.

ОглавлениеTV isn’t like films, radio or the stage. It has bits of all three in it, of course. But it is something demanding a new approach.

Terry-Thomas, Answers, 6 October 1951

COMIC GENIUS HAS THE habit of springing up in several places at once. About the time Ernie Kovacs was conducting his early Pennsylvanian experiments, Terry-Thomas, the gentleman’s gentleman comic, was regaling BBC audiences with How Do You View? Written by Sid Colin and Talbot Rothwell, this loose assemblage of sketches and monologues pioneered countless bits of televisual business: the deadpan nonsense interview (conducted by linkmen Leslie Mitchell and Brian Johnston); mock home movies; the constantly-interrupted speech; and the random foray off the set and around the cameras, booths and assorted detritus of the studio, just for the hell of it. Its success in those sparse early days was considerable, although critics were snooty. ‘I should not care to say,’ ventured a confused C. A. Lejeune, ‘whether the presentation is more formless or the material more inept.’35

While ‘T-T’ was in his pomp on TV, the BBC Home Service was plagued by an infestation of nits. The Goon Show didn’t so much break the rules of radio comedy as blithely caper on to the air in complete ignorance that any existed in the first place. With its cast of vocal grotesques and relaxed approach to the laws of cause and effect, it became an unhinged institution to a nation still recovering from the similarly lunatic privations of war. Two Goons – writer Spike Milligan and voice-of-them-all Peter Sellers – joined forces with young American director Richard Lester to translate their formula to independent television, in the form of The Idiot Weekly, Price 2d.

The fusty periodical of the title, inspired by the florid world of Daily Express humorist Beachcomber, provided an extremely tenuous jumping-off point for a bewildering array of skits, with Sellers playing Edwardian schoolmasters and gentleman boxers, ‘Footo, the Wonderboot explorer’ and even much-loved Goon character Bluebottle. Blackout gags included an expectant audience sat before a curtain, which was raised to reveal another audience, facing them. Singers like Patti Lewis got a custard pie in the face. This time, the critics had caught up with the viewers: even the Daily Mail dug this ‘bubble of nonsense which stayed miles above the surface of reality.’36

A few months later the same gang made A Show Called Fred, which scrapped the magazine trappings and intensified the lunacy. As the Daily Mail noted, The Idiot Weekly ‘made a few grudging concessions to the audience, in as much as it was possible to follow the jokes by the ordinary, accepted sense of humour. Fred makes no concessions at all.’37

A typical edition of Fred began with Spike, dressed in rags, mooching around the Associated-Rediffusion studio corridors: a parody of the Rank Films gong (which Terry-Thomas also lampooned) and credits for ‘the well-known Thespian actors’ Kenneth Connor and Valentine Dyall (usually clad in bow tie, dinner jacket and no shirt). There would be mock interviews with insane individuals, often called Hugh Jampton, commercials for ‘Muc, the wonder deterrent’, and viewer query slot ‘Idiots’ Postbag’, presented in front of a projected backdrop of open sea, or a burning building. (‘Dear sir, do you know what horse won the Derby in 1936?’ ‘Yes, Mr Smith, I do.’)

Even by the primitive standards of the day, the thing was heroically shoddy. Backdrops wobbled and frayed at the edges, costumes were either half-complete or non-existent, and in the frequent pull-out shots to take in backstage crew and chunky EMI cameras, the floor was visibly covered in studio junk. As with Kovacs’s shows, laughter came from the camera crew rather than an audience. Fred ended with an extended parody of the various po-faced dramas with which it shared the schedules. Soap opera The Grove Family became ‘The Lime Grove Family’: ‘Mum’ cooked roast peacocks’ tongues on baked mangoes in the piano, whereupon ‘son’ hit her with a club, and was reprimanded by ‘dad’, saying, ‘You mustn’t hit your mother like that. You must hit her like this …’ Their version of The Count of Monte Cristo featured the first appearance of the famous coconut-halves-for-horses’-hooves sight gag and ended with the destruction of the already threadbare set, a rousing chorus of ‘Riding Along On the Crest of a Wave’, and Valentine Dyall doing the dishes in the studio’s self-service canteen.

Descriptions like this are hopelessly inadequate. As Bernard Levin put it, ‘if you do not think that is funny it is either because I have failed to convey its essence or because there is something wrong with you.’38 Peter Black agreed: ‘This show has built up in three weeks a following that has gone beyond enthusiasm. It is an addiction.’39 Critical credentials notwithstanding, these men were television comedy’s first fanboys.

When stuff like Fred appeared on the continent, it was Absurdist theatre, afforded its rightful place in the cultural pantheon. Over here it was just British rubbish. Bernard Levin tried to redress matters, asserting that the Fred team ‘have done television a service comparable to that rendered by Gluck to opera, or Newton to mathematics.’40 Philip Purser claimed Fred was ‘roughly equivalent to the revolution in the theatre promoted by Bertolt Brecht; and not entirely dissimilar.’41 It certainly created its own version of Brecht’s Alienation Effect. ‘I had to make a very real effort of will on Wednesday,’ recounted Levin of trying to watch Gun-Law, the bog-standard western which followed Fred, ‘to convince myself that this was not meant to be funny. For a long time I could not stop expecting Mr Spike Milligan to put his mad, bearded head round the corner of the screen with some devastating remark about the shape of Sheriff Dillon’s face.’42

Milligan’s TV year ended with Son of Fred, available for the first time in the north, with cartoons by Bob Godfrey’s Biographic Films, mocked up technical breakdowns and Gilbert Harding’s Uncle Cuthbert playing the contra-bassoon while suspended from wires in a wheelchair. (‘Kind of an aerial fairy,’ he explained.) It also inaugurated the grand tradition of putting jokes in the TV Times listings. (‘Frisby Spoon appears without permission.’) In 1963 a compilation, The Best of Fred, was presented to a public that, claimed ITV, had now ‘caught up’ with Milligan’s anarchic humour, with Milligan and Dyall reminiscing over the show’s distant heyday in between clips. Innovation had become nostalgia.

Lester would go on to give the Beatles silly things to do on film. Milligan inaugurated the Q series in 1969, which took his illogical methods down increasingly strange paths. Meanwhile his former co-Goon Michael Bentine cooked up a more technically elaborate version of the same mayhem for the BBC’s It’s a Square World. But Fred’s place in history would be secured by countless other hands. All around the country, short-trousered future members of Python, The Goodies and other anarcho-comic collectives were watching closely and making mental notes. As Peter Cook would later note, Milligan ‘opened the gate into the field where we now all frolic.’43