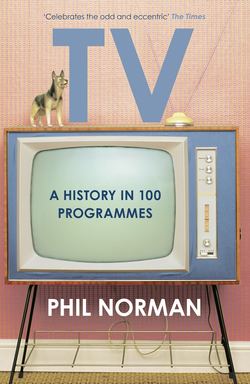

Читать книгу A History of Television in 100 Programmes - Steve Berry, Phil Norman - Страница 28

PLAY SCHOOL (1964–88) BBC2 The BBC loosens its old pre-school tie.

ОглавлениеAnyone can fill time with pap and the kids will watch it. It’s safe and it’s easy. We are trying to break away from that.

Joy Whitby, Play School executive producer, 1966

THE BBC’S EARLY CHILDREN’S television was a fortress of twee. Amiable (if slightly grotesque) puppets would get into a jolly old fix, patrician ladies would trill nursery rhymes in strident falsetto, and improving fables would be slowly read out of leather-bound books the size of shed roofs. When Doreen Stephens took charge of the BBC’s family programmes in 1963, this had been the case for rather too long. She found a ‘demoralised, miserable children’s department’129 plodding along with the same Andy Pandy mindset that harked back to before the Suez Crisis. Her initial desire to scrap Andy, Bill and Ben outright was countermanded by an early manifestation of popular nostalgia, but she did gradually phase them out in favour of The Magic Roundabout, Camberwick Green and a new daily morning programme for the under-fives.

Stephens employed Joy Whitby to edit Play School. With two presenters, a tiny studio, a clock for telling the time and an initial weekly budget of £120,130 Whitby concocted a feast of ideas, songs, rhymes and (very basic) documentary films designed to stimulate toddlers’ imaginations. The fustiness of old gave way to bold designs and plush soft toy companions (though Hamble, a grotesque china doll, was the one anomalous throwback to morbid Victoriana and suffered chronic abuse from presenters and technical staff as a result, before being replaced in 1986 by the marginally less creepy Poppy). In a reversal of the usual metrics, the programme was judged a success by its makers if children abandoned the show half way through to go outside and do a wobbly dance or search for round things.131

If this sounded like a tepid bath of liberal unction, the third woman involved in Play School’s inception, series producer Cynthia Felgate, added a tougher note. ‘Talking down is really based on the assumption that you are being liked by the child,’ she reasoned. ‘But if you imagine a tough little boy of four looking in, you soon take the silly smile off your face.’132 As a former actor with a theatrical troupe specialising in that toughest of gigs, the in-school educational performance, she knew whereof she spoke.

An experienced general, Felgate recruited troops from the ranks of repertory, with a sharp eye for nascent talent. Play School staff would take roles in countless other children’s programmes after their toil at the clock-face. They included musicians, from the classically trained Jonathan Cohen to the folk-schooled Toni Arthur and the downright countercultural Rick Jones. The show also pioneered, in its own quiet way, the employment of non-white hosts, beginning in 1965 with Paul Danquah, fresh from filming A Taste of Honey. Humour played a huge part in proceedings, courtesy of Fred Harris (who graduated to adult comedy when radio producer Simon Brett chanced upon his work while, appropriately, off sick), Johnny Ball (soon to launch his own one-man science-and-puns initiative Think of a Number), Phyllida Law (sharing the arch eccentricity of her husband Eric Thompson, Magic Roundabout narrator and fellow School player), and virtuoso mime Derek Griffiths. Add to this a roster of guest storytellers from Roy Castle to Richard Baker, George Melly to Spike Milligan, and you had a clubhouse of wits in the front room daily: the Algonquin Round Window.

Play School was born with the BBC’s second channel, the first scripted programme the morning after BBC Two’s notoriously blackout-blighted launch. It became such a fixture that households equipped with sets new enough to receive the new UHF channel were often invaded by the children of less well-off neighbours round about eleven o’clock. Camera operators, who suffered previous Watch with Mother efforts under duress, actively fought over the chance to cover Play School.133

In 1971 there came a spin-off, the altogether less restrained Play Away. Eminent Play School old boy Brian Cant, ‘merry as a stoned scoutmaster’134 in one critic’s memorable description, led cohorts including Jeremy Irons, Tony Robinson and Julie Covington through groansome puns, venerable slapstick routines and jolly songs which could, like the catalogue of gargantuan consumer goods ‘Shopaway’, become mildly satirical. This all-year panto became big enough to transfer to the Old Vic in 1976.

Play Away’s high standards drew high expectations from its audience. George Melly observed that while children never questioned the knocked-off likes of Pinky and Perky (rudimentary puppets jerking up and down to grating pitch-shifted covers of pop hits), when faced with the higher craft of Play School they ‘become almost Leavisite in the severity of their criticism’.135 The ability to spot quality among the dross was learned at an early age.

A few years in, the School started to expand. By 1970 it was playing, in recast local versions, everywhere from Switzerland to Australia, with the use of a specially assembled ‘Play School kit’. Most of the toys made the transition to other cultures more or less intact: Humpty, for instance, became ‘Testa D’Uovo’ – Egghead – in Italian. Unlike the conquering franchises of children’s television to come, Play School established more of a commonwealth than an empire, importing songs from Israel and films of Roman ice cream factories as it exported Norwegian translations of The Sun Has Got His Hat On. (The Scandinavian connection, which culminated in a joint TV special between the UK and Norwegian Play Away franchises, highlighted an interesting difference in approaches to children’s television. A 1973 Danish seminar on kids’ TV produced a twelve-point list of good practice, a copy of which was pinned up in the BBC children’s department in Television Centre’s bleak East Tower. Alongside the expected exhortations to honesty and clarity was the suggestion: ‘When you want to tell an exciting story, try to relate its conflict to the central conflict in society between labour and capital.’136 If this particular directive was acted upon at the Beeb, it was well disguised.)

Like all timeless children’s programmes, Play School became a slave to adult fashion. A much-publicised ‘moving house’ in 1983 altered the theme tune, redesigned the studio and replaced the magic windows with ‘shapes’, to the horror of many parents who’d grown up with the old show themselves. Five years after that the school was closed for good, replaced by Playbus, made by the newly independent Felgate Productions, which was ‘more attuned to the needs of today’s children’ and featured children in the studio – one of the original Play School’s prime taboos. The intuition of a handful of creative producers was replaced by a squadron of educational advisers and child psychologists. No longer would British kids have their formative years soundtracked by vintage songs such as Little Ted Bear From Nowhere in Particular and Ten Chimney Pots All In a Row (When Along Came a Fussy Old Crow). There’s progress, and there’s progress.