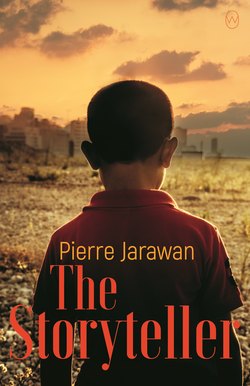

Читать книгу The Storyteller - Pierre Jarawan - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление-

4

Father was quick to realise how important it was to learn German. After fleeing burning Beirut in spring of 1983, the first refuge my parents found in Germany was the secondary school’s sports hall in our town. The school had been shut down the previous year when routine inspections during the summer holidays had revealed excessive levels of asbestos in the air. But there were no other options, so the sports hall ended up as a refugee reception centre. Father soon managed to get hold of books so that he could teach himself this foreign language. At night, while others around him slept wrapped in blankets on the floor, he clicked on a pocket torch and studied German. By day, he could sometimes be seen standing in a corner, eyes closed, repeating vocabulary to himself. He learned fast. Soon he was the one the aid workers sought out be their interpreter. Then he’d stand, a circle of others around him, and explain to the aid workers in broken German which medicine people needed or what it said on the certificates and documents they held out to him. My father was no intellectual. He’d never been to university. I don’t even know whether he was smarter than average. But he was a master of the art of survival and he knew that it would be to his advantage if he could make himself indispensable.

The atmosphere in the sports hall was often strained. People who had arrived here with no possessions, nothing but hope for a new life, were now condemned to wait for their fate to unfold. The air was stuffy, the space cramped. A constant hum of voices hovered beneath the ceiling; there was never complete silence. At night, you’d hear children crying or mothers weeping, and the snoring, scratching, and coughing of the refugees. If one got a cold, many were sick a few days later. The aid workers did their best, but there were shortages of everything: medicine, toiletries, food, not to mention toys for the kids, or ways for the grown-ups to keep themselves busy.

Losing their homeland was a fate everyone shared; they were all refugees. But a residence permit was also at stake, and not everyone would be allowed to stay; they knew this too. Everyone had witnessed scenes in which screaming mothers clung to the poles holding up the basket-ball hoops as they resisted being carried out of the hall along with their children. Here, one person could be the reason why another didn’t get to stay. That made fighting a serious problem. But settling fights was another thing Father was good at. He’d talk calmly and persuasively to the irate parties, stressing how important it was not to cause trouble, how it helped to make a good impression, because news of what went on in the hall would inevitably find its way to the outside world. Sometimes there were indeed people outside the hall, holding placards that said there wasn’t enough room in this town for so many people.

There were others too, people who brought bags of clothes—even if they were in the minority. And many of the refugees began to see my father as an authority, someone they could go to with their worries. “We’re people too,” they’d complain, “not animals, and yet we’re locked up in here.” Or, “In Jounieh, I was a lawyer. I had a practice that got destroyed. Where am I meant to go if I they won’t let me stay here? Go back? There is no going back. I have no house, no family …” And Father agreed with them, though never absolutely. He always stressed how important it was to understand the people outside the hall, that they were probably afraid, the way lots of people fear the unknown. The more crowded the hall became, the trickier the situation became. People would suddenly overreact, but it wasn’t only due to stress and uncertainty. Religious differences could also trigger insults and fist-fights. Many of the Lebanese refugees divided their camps up along religious lines. And so our sports hall mirrored the streets of divided Beirut: Muslims on the left, Maronite Christians on the right. Each blamed the other for their misfortune—for having lost everything, for being refugees, for having to live in a sports hall.

My father’s friendship with Hakim was another thing that lent him authority. Hakim and Yasmin, who was barely two at the time, were Muslims. My parents were Christians. They had all fled Beirut together. Hakim and Yasmin were camped right beside my parents—in the Christian sector of the hall, so to speak. But Hakim encouraged his daughter to play with all of the kids, making no distinctions. My father and Hakim would say to the others, “We’re not in Lebanon anymore. We all came here because we want peace, not war. It’s not about Christians and Muslims here. It’s about us. As Lebanese people.”

But sometimes words were in vain. One night, Father was woken by a dull thumping, the sound of something hard rhythmically pounding something soft. Fumbling in the dark and aware of my mother breathing gently beside him, he sat up. All he could hear in the dark hall was that noise. He made his way towards its source, putting one foot carefully in front of the other to avoid stepping on sleeping bodies. In the dim shadows he could make out one figure bent over another. But he was too late. Father could see the battered face even as he leaned in to grab the shoulder of the man who was straddling his victim and punching him like a man possessed. The woman closest to them began to scream. Someone turned the lights on and people sat up suddenly, looking around in shock. More and more people started screaming. There was blood not just on the floor, but all over the hands and clothes of the man who had killed the other. Four men grabbed him and pinned him to the ground until the police arrived.

For a while, the dead man’s place in the hall remained empty, and his death seemed to put an end to the fighting too. But more people were arriving in the sports hall every day, so it wasn’t long before someone spread his blanket in the free space to lie down and sleep. After a few days, it was impossible to say where exactly the empty space had been.

Meanwhile, Father’s German improved by the day. For him, the ability to master this language was inextricably linked with the fate that awaited him and his wife. Because he knew how important it was, he tried to teach Hakim what he learned too. In the evenings, he used to tell stories in the hall. In the beginning, he sat on the floor surrounded by children, their eyes wide, their mouths agape. He told them about a giant spaceship that brought everyone to the bountiful planet Amal. Different coloured lines on the floor of the spaceship led the way to the magnificent bathrooms or the splendid dining hall or the cockpit. In his head, Father had converted the sports hall into this spaceship. The dingy showers in the changing rooms became a hi-tech spa in which little robots scrubbed people’s backs. The side-lines of the basketball court became energy-acceleration tracks, perfect for a kids’ game in which all they had to do was take a running jump onto this line in order to whizz all around the spaceship at great speed. Its captain was a crazy camel who entertained the passengers with comical announcements. Father put on a funny voice for this purpose, making the children crack up. In Arabic, amal means hope. Soon everyone in the sports hall was familiar with the planet called Hope. Sometimes when even the grown-ups could no longer hide tears of despair and exhaustion from their children, the little ones could be seen stroking their cheeks, saying “It’s not far to Amal now.”

It wasn’t long before parents began to join the circle around Father, and a few days later, some of the aid workers were also listening in. Soon this story time became a regular fixture, an evening ritual that brought people together. It was the only time when no one spoke but Father. His reassuring voice floated above the listeners’ heads and filled them with a wealth of imagery.

These days, having learned so much more about him, I often wonder how he managed to keep his secret. And I always come to the same conclusion: his ability to escape reality must have helped him.

Hakim’s asylum application was approved before my parents’.

As a single father, with passable German to boot, he and Yasmin could expect to get a permanent residence permit in the near future. My parents hugged and kissed them goodbye and waved them off when they left the sports hall. Their next stop was a little social housing flat on the edge of town. A few months later, Hakim also got a work permit and found a job in a joinery. He had played the lute all his life and had no trouble convincing the master joiner, who had a soft spot for refugees, that the calluses on his fingers were from years and years of working with tools. He enjoyed the work too. Being a lute-maker’s son, he loved the smell of wood. Hakim had spent many childhood years in his father’s workshop before heading to Beirut to become a successful musician.

My parents had to stay on in the hall for another while. When they eventually got the preliminary approval letter, many tears were shed. Mother cried tears of relief. Some of the grown-ups cried because they couldn’t imagine the sports hall without my father. And the children cried because their storyteller was leaving. It was a Tuesday when the man arrived and started looking around the hall. An aid worker who had been leaning against a door pointed him in the right direction, and he made a bee line for my parents.

“Are you Brahim?”

“Yes,” said Father.

“Brahim el-Hourani?”

“Yes, that’s right.”

“And you are Rana el-Hourani?” he asked my mother.

“Yes,” she confirmed.

“A letter for you.” And when he noticed how Mother shrank back a little, the man smiled and said, “Congratulations!”

And so Brahim the storyteller left the sports hall. Nearly everyone wanted to say goodbye. People came to wish my parents good luck, reassuring each other that they’d soon meet again, in town, as ordinary citizens, at the cinema, shops, or restaurants.

Brahim. That was my father’s name. Brahim el-Hourani. Rana was my mother’s first name. The el-Houranis—those were my parents. I didn’t exist yet.

My parents got a flat in the same housing scheme as Hakim and Yasmin. Fate and a few case workers had been kind to them. They ended up living only a few hundred metres apart. And Father, whose German was pretty good by then, also got a work permit within a few months. Mother once told me how he went off to the Foreigners’ Registration Office with a bag of freshly baked baklava and put it on the baffled official’s desk.

“My wife made that for you,” he said.

“Oh,” said the official, “I can’t accept that.”

“It’s for the stamp,” said Father.

“The stamp.”

“On the work permit.”

“Ah. The stamp,” said the official, looking from Father to the plastic bag on his desk and back to Father again.

“We’re very grateful to you.”

“I’m afraid I can’t accept it,” the man repeated, clearly embarrassed.

“Please. I am a guest in your country. Regard it as a gift for the host.”

“I can’t.”

“I won’t tell anyone.”

“The answer is still no.”

“I saw what’s on the menu in your canteen today,” said Father. “Believe me, you do want this baklava.”

“I’m sure it’s perfectly delicious baklava,” protested the man, “but I’m afraid I can’t accept it.”

“Maybe I should have a word with your boss?”

“No,” cried the official. “No, Mr. …”

“El-Hourani. You can call me Brahim.”

“Mr. el-Hourani, please give my regards to your wife and tell her what a pleasant surprise this was. But my wife is baking a cake this evening, and if I eat your pastries beforehand, I’ll be in trouble at home.”

“In trouble? With your wife? You’re not serious.”

“I am serious.”

“Well, we don’t want that, do we,” said my father.

“No, we don’t.”

“All right, then.” Father took the bag off the desk. “Thank you very much for your help all the same. And if you ever do fancy some baklava, just give us a ring.”

Then Mother recounted how Father came home and declared with a sigh, “In Beirut, if you need something stamped, you take baklava to the guy with the stamp beforehand. Here they won’t even accept the baklava after they’ve given you the stamp.”

The official didn’t forget my father in a hurry. How could he? He saw him on three further occasions, when Father accompanied men he knew from the sports hall. Each time, he asked the official for a stamp. Each time, he got it.

The preliminary decision was soon followed by the final one. My parents were granted asylum and received permanent residence permits as well. Father got a job in a youth centre where many foreign kids spent the afternoons. He helped them with German after school, and they were happy to learn from him as he was such a good role model. He earned a lot of respect among the youngsters. One time he managed to invite a well-known graffiti artist to the centre. Between them they sprayed and decorated the grey exterior, transforming it into a colourful landscape full of Coca-Cola rivers, lollipop trees, and chocolate mountains with ice-cream peaks. A bit like the wonderful planet Amal.

Mother loved sewing. She would buy fabric at knock-down prices at the local flea market and make up dresses on a sewing machine that also came from the flea market. Father set up a corner for her in the living room, and she’d work in the pool of light cast by a desk lamp that wasn’t quite tall enough, threading the needle and guiding the fabric with steady hands as the machine stitched and whirred. She sold the dresses through thrift shops, often earning ten times what the fabric had cost her. When she’d saved up enough money, she had business cards printed and designed a label to sew on to the dresses. “It doesn’t matter which you choose: Rana or el-Hourani,” Father said, “They both sound like designer labels.” She went for Rana, and that became her brand name. One afternoon—I was six maybe—Mother got a phone call. It was Mrs. Demerici, whose surname, according to Mother, was actually Beck, except she’d married a Turk, the man who owned the thrift shop not far from the pedestrian shopping area. When Mother hung up, her face was glowing with pleasure. “A woman who bought one of my dresses wants to meet me,” she exclaimed, grabbing my hands and dancing round the tiny living room. This was in our old flat, where I had been born in 1984. The woman’s name was Agnes Jung, it transpired, and she really liked mother’s sewing. Agnes Jung intended to change her name to Agnes Kramer in the near future, wanted Mother to make her four bridesmaids dresses, and was willing to pay so handsomely that Mother almost fainted before she managed to collapse into the living-room armchair. She spent the next few weeks sewing day and night. The bridesmaids eventually came for a fitting, and Mother kept making apologies for the neighbourhood and the size of our flat, and saying how much she hoped the ladies liked the dresses. They disappeared into my parents’ bedroom for the fittings, and Mother put the key in the door from the inside so that the keyhole was no good to me.

When Yasmin and I were little, she spent a lot of time in our house. Hakim was in the workshop during the day. My mother sewed from home, and Yasmin was like a daughter to her. We got on well. What I liked about Yasmin was that she never made me feel like a little boy, even though she was two years older. Her eyes were dark brown and incredibly deep, and her long black curls always had a glossy shine. Her hair was usually falling into her face as if she’d just come through a storm. There was something untamed and boyish about her, but only when we were rambling around the flats on our own. She’d break branches off trees and drag them behind her, as if she was marking a boundary. She was better at climbing than me and never tore her clothes. There was an aura of effortlessness about her, yet you were sure to fail if you tried to compete. The results were obvious: I was always coming home with new holes in my trousers and pullovers, which would have to be patched and darned by Mother. Yasmin was quite the chameleon—in adult company, she was always perfectly behaved. She was polite, said thank-you for her dinner, and, unlike me, never put her elbows on the table during meals. She could also be patient and sit still for ages while Mother ran the brush through her hair over and over. I don’t think any of the grown-ups would have believed me if I’d told them the other things Yasmin got up to.

That flat, in which I spent the first seven years of my life, was too small for three people, and describing it as dingy would be an understatement. Nearly all the walls were stained, and they were paper-thin too. Pots clattered constantly through the walls, TVs were too loud, heavy shoes clomped on bare floorboards. You didn’t even need to strain your ears to hear what the neighbours were fighting about—if you could understand the language, that is. There were many different nationalities in this housing scheme: Russians, Italians, Poles, Romanians, Chinese, Turks, Lebanese, Syrians, and even a few Africans—Nigerians, I think. The satellite dishes on our balconies pointed in many different directions. Between the buildings, in the middle of a walled courtyard, there was a tiny playground. A bunch of older teenagers usually hung out there, smoking. It was full of broken glass, and if there was a lot of rain, the playground flooded and turned into a mucky lake. Yasmin and I never went there to play. In front of the buildings, the bicycles at the bike stands nearly always had their saddles or wheels stolen. And if you only locked your bike to the stand by the front wheel, you could be sure the frame would be gone the next day. Even buggies got stolen from halls and landings.

Sometimes Yasmin and I would try to sniff out where the different families hailed from—a “guess which country” game to keep ourselves amused. We’d walk along the dark passageways, their walls smeared in permanent marker, the neon lighting usually flickering, and the smell of disinfectant everywhere. When we were sure no one could see us, we’d go down on our knees or lie on our stomachs for a few seconds and put our noses to the crack of a door. Because there’d always be someone cooking somewhere, and we’d try to guess from the spices and other ingredients where the occupants came from. Mostly the smell was of cooking oil though, and very occasionally the door of the flat would open the minute we lay down in front of it. Then we’d jump up and scarper down the stuffy stairwells until we were completely out of breath. Once we’d reached safety, we’d laugh triumphantly, our lungs screaming for air, our hearts thumping wildly.

The many passageways, nooks, and crannies in our blocks of flats were a paradise for children who loved secrets and needed space away from the world of grown-ups. The grown-ups’ world—in our flats, that meant the faces with downturned mouths. The parents with tired eyes who dragged themselves and their shopping bags up the stairs we hid under. Or the raised voices that filtered through the doors like the songs of sad ghosts.

One day when Yasmin and I were wandering aimlessly through the stairwells, not registering which turns we were taking, we ended up in the basement, in front of a door with peeling paintwork that we’d never seen before. Yasmin pushed the handle down gingerly. The door wasn’t locked. Behind it was a small room and a pallet bed with a crumpled purple sleeping bag on it. The floor was littered with empty beer and schnapps bottles, and we found lots of syringes near the bed. There was no window, just an air vent with a thick layer of dust on the grating. The air was musty and a nasty smell assaulted your nose every time you inhaled. But there was also a shelf with tools on it—a hammer, pliers, wire, some rubber hose. And a large box full of artificial flowers. We had stumbled on what used to be the caretaker’s cubbyhole. At one stage, our flats had a full-time caretaker, and this was presumably where he hung out. Now all the maintenance work was handled by the local authorities, and they only sent someone out as a last resort. This little room must have served as a hide-out for homeless people or junkies for quite some time. Yasmin took a flower from the box—there were a couple of hundred in it—and dusted the petals off on her sleeve. They were red.

“This is no place for a flower,” she said, looking at the colourful object in her hand, which seemed as out of place among all the greys as a Pop Art print in a prison cell.

“I have an idea,” she said, her brown eyes twinkling.

Adventure beckoned, I followed.

We sneaked back to the cubbyhole several times over the following days. Once we were sure everything stayed exactly the same between visits, we could safely assume that no one lived there anymore. We had found a secret place of our own, a magic room in an enchanted realm. It was Yasmin’s idea to take the flowers to the world of grown-ups and brighten it a little. “Everyone loves flowers,” she stated categorically, and there was no contradicting that. But there were more flats in our place than we had flowers, so we decided on a selection process: “Whenever we hear fighting or see someone sad going into their flat, we’ll put a flower outside their door,” she decided. “But they only get the flower once.”

After that, whenever we heard someone shouting while we were on our rambles, we chalked a small cross on the bottom right of the door frame so that we’d find it again. Sometimes we hid round a corner so that we’d see people’s reaction to the surprise splash of colour in the daily grey. We never actually saw anyone coming out, but when we went back to the scene later, the flowers were always gone. So we imagined the people finding them, picking them up, and smelling them. They’d peer furtively up and down the corridor before closing the door and putting the flower in a vase in the window, even though the flower wasn’t a real one. We had great fun with this flower game; when we’d go back to the flat, Mother would ask what we’d been up to, but we never said a thing, just exchanged surreptitious smiles across the table.

There was often trouble with the police in our flats. Some of the kids hanging around the playground boasted that we lived in a place the cops were afraid to go after dark. They claimed to be kings of the streets once the sun went down. But it wasn’t true. The police often came after dark. We’d see them and their torches through the window, entering one of the blocks and reappearing a short time later, hauling someone off to the station. The cops were definitely not afraid of our place, and I often saw them picking up one of the so-called kings.

If where we lived bothered my father, he didn’t let it show, though I may have been too young to notice. He liked his job in the youth centre, and Mother managed to build up a regular customer base for her dresses. They were content, my parents, but money was always scarce. Father regularly had to send money home to his mother, my grandmother, who had refused to leave the country when they did. He explained this to me many times. The money was mainly for doctor’s bills and medicine. One day when I asked why she hadn’t left with them in the first place, or why she couldn’t at least join us in Germany now, he just smiled and said, “It’s Lebanon. No one wants to leave.”

During our seventh year in that flat, Mother became pregnant for the second time. Now the place was definitely too small, and since we lived on the sixth floor, and the lift broke down almost every day, my parents decided it was time to move. Hakim agreed. Yasmin and I were thrilled. Besides, we had run out of flowers by then.