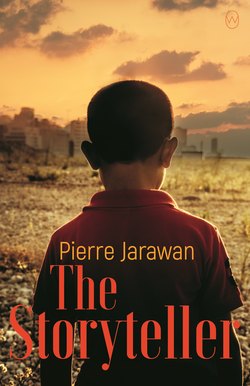

Читать книгу The Storyteller - Pierre Jarawan - Страница 20

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление-

9

My excitement grew by the day. I couldn’t wait to be transported once more into the magical world of Abu Youssef and Amir, a world full of heroes and rascals, colourful costumes and glorious adventures. I recalled some of the earlier episodes, like the time Abu Youssef had to rescue Amir from Ishaq, a lizard-like animal dealer who had kidnapped Amir and was threatening to sell the talking camel to a circus in Paris. Ishaq was a formidable foe who had enslaved many animals because of their extraordinary talents. Among them was an extremely overweight rhinoceros who was unbeatable at cards. On full moon nights, Ishaq would turn into a green-eyed lizard with impenetrable black scaly armour. Abu Youssef used a clever ploy to rescue Amir. He knew that Ishaq’s one weak spot was his fear of fire. So Abu Youssef followed the lizard man across the stormy sea to Paris, where the dealer intended to negotiate the sale of his extraordinary asset to the circus director. Then Abu Youssef challenged Ishaq to a duel. It took place at the Arc de Triomphe by the light of the full moon. Abu Youssef defeated his rival by forcing him into the eternal flame that burns in the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier.

All sons love their fathers, I believe, but I positively adored mine. He allowed me into his wild fantasies; he took me with him to worlds of wonder fabricated in his head; he intoxicated me with his words. He had made me promise something else early on—never to tell Mother what his stories were about. “If she finds out that I’m telling you stories about men who change into lizards every full moon, I’ll get into trouble,” he said with a wink. I nodded vigorously and promised to keep our secret.

Yasmin knew all about Abu Youssef too. She was green with envy when I told her Father was going to tell me a new episode soon. “Will you tell it to me later?” she asked. Her eyes gleamed like a sunlit lake. We had developed our own ritual. Father would tell me a story, and I’d then retell it to Yasmin. This made me proud to be a storyteller too, and I loved it when Yasmin listened as I repeated Father’s words. She’d close her eyes tight and listen intently, and I could almost see the magic worlds opening up inside her head. It was as if we had created our own theatre, and Yasmin was the lighting, the stage, and the audience. I had no stories of my own yet, just my voice, my body. So a little boy would stand in front of a little girl and wave his arms about to represent the wind blowing in Abu Youssef’s face, or dance on tiptoes to show how he crept up on an enemy. I whispered when Abu Youssef whispered, and I screamed when Abu Youssef screamed. Yasmin loved it, and nothing could beat her peals of laughter and applause at the end.

The first snow arrived a few days after my birthday, like cotton wool drifting down from the sky. It settled on the rooftops and the now bare branches of the trees, transforming everything into a glittering wonder. I woke up to the sound of a snow shovel on the pavement and sat up instantly. From my window I could see Hakim, his ears bright red, clearing the snow off the pavement. He waved up when he saw me. “Didn’t I tell you the snow wouldn’t be long in coming?” he shouted and laughed. I laughed too. Frost flowers had grown on the windowpane overnight. They were my favourite flowers, partly because you didn’t have to water them.

That afternoon Hakim took Yasmin and me up the nearby hill to try out my sled. We sat one behind the other, with Hakim puffing and panting as he hauled us through the snow. Father didn’t come. By now I’d almost grown used to his strange moods. The day after he’d promised to tell me another story, for example, there he was, pacing up and down again like a caged animal. The telephone had rung a little while earlier and Mother had answered it. She’d said “Hello?”, repeating it in a loud voice several times, then hung up. Around half an hour later, Father slipped out of the flat. I knew he was going to ring Grandmother, but I resisted the urge to tell Mother she needn’t worry.

Besides, the arrival of the snow meant there were far more important things on my mind. When I’d come down in my snowsuit, Yasmin was already out the front in her red hat and gloves, armed with a perfectly formed snowball. Now we were sitting on my new sled, urging Hakim to pull us faster, and roaring with laughter when he whinnied like a horse. We lost track of time as we whooshed down the slope over and over again. The air was cold and clear and full of shrieks of joy. Our cheeks were red, our eyelashes frosted over, our noses ran, but we barely noticed. Winter had come, the time for family fun. The air smelled of cinnamon and tangerines instead of damp cold and dead leaves, of log fires and cloves instead of chestnuts and musty earth. We left sled tracks in the snow. We were happy.

The hours flew by, and suddenly we realised it was dusk. “That’s enough for today,” shouted Hakim, his eyes gleaming with the cold. “There’s plenty of winter yet. Next time we’ll take the car and find a bigger hill.” We protested, but only half-heartedly, as we could feel a pleasant tiredness taking hold. If Hakim was tired, he didn’t show it. He just whinnied cheerfully and pawed the snow before pulling us home.

When we got home, the smell of hot punch already filled the whole stairwell. Yasmin and I pushed past each other into our flat, quickly discarded hats and gloves, and clambered out of our snowsuits. Mother was already waiting with two steaming mugs.

“You’re frozen to the bone,” she remarked, stroking our cheeks.

We were indeed, and all the more glad to wrap our hands round the warm mugs. Hakim closed the door behind us and knelt down to pick up the hats and gloves we had carelessly tossed on the floor.

“Give that pair a sled and a hill and they don’t just forget the time, they forget their manners as well.”

Mother smiled gratefully, relieved him of our things, and handed him a mug of punch. He closed his eyes and held it to his cold cheek. Then he followed us into the kitchen.

“Where is Brahim?” he asked, poking his head into the living room.

“He’s not back yet,” said Mother.

“When did he leave the house?”

“This morning.”

Hakim raised his eyebrows and looked at the clock above the kitchen door. It was just after six. He’d been gone over seven hours.

“Do you know where he went?”

“No.”

Mother sighed. Hakim frowned and took a seat. Outside, darkness had descended.

Mother turned to us. “Tell me all about the snow.” She gently pushed a lock of Yasmin’s hair out of the way before she bent over her cup.

We regaled her with our adventures on the slopes, each trying to outdo the other’s descriptions of breakneck speeds and spectacular falls into the deep snow. Even Mother laughed out loud when we described our draught horse, Hakim. She really was so pretty when she laughed.

We sat in the kitchen for about an hour, drinking punch and eating our supper. Then we went into the living room. Yasmin and Hakim had gone downstairs briefly and reappeared in cosy sweaters. The four of us were wrapped up on the sofa now, the warmth of the heating behind us and a soft blanket tucked round our feet. Yasmin and I had found some notepaper and were making out our Christmas lists. I wanted a bike and Yasmin wanted a new schoolbag. Hakim was asking Mother about her sewing and her latest ideas. He had one of her sketchbooks on his lap and was running his flat fingertips over the drawings as if he could feel the fabrics’ weft and weave. Mother was using the drawings to explain the different steps in her work and telling Hakim about a Christmas market where she was hoping to buy material at a keen price. Hakim already knew about the market. His boss had suggested that he carve nativity figurines to sell there and asked if that would be a problem for a Muslim. It was no problem for Hakim, of course.

We were so absorbed that we never even heard Father coming in. I’ve no idea how long he had been standing there before we noticed him. Mother startled as if she’d got an electric shock. Hakim looked up and the sketchbook fell from his hands. Yasmin dug her nails into my arm. Father stood there in the doorway, staring at us like we were ghosts. His clothes were all wet and crumpled, his face as grey as a November morning. Time seemed to stall for a moment. Water dripped from his hair and beard onto the wooden floor. A puddle had already formed around his feet. Then he closed his eyelids, raised his hands, and pressed the insides of his wrists to his temples, as if he’d felt a jolt of pain. It was as if he couldn’t bear the sight of us and hoped we’d be gone when he opened his eyes again. But we still sat there, motionless, staring back at him. He lowered his hands, turned, and stumbled out of the room. A few seconds later we heard the click as he locked himself into the bathroom.

When I was younger still—three or four maybe—I almost drowned. It was summertime. A small river flowed through our town, and its grassy banks were very popular once the weather grew warmer. On a sunny day you’d see couples sprawled on rugs rubbing sun cream on each other’s backs, popping luscious strawberries into each other’s mouths, and gazing at each other with bedroom eyes. Youngsters with blaring boom boxes cooled their beers in the water; toddlers in nappies waddled across the grass, trailed by tail-wagging dogs; young guys playing football in their swimming trunks grinned cheeky apologies when they happened to hit the bikini-clad girls feigning disinterest at the edge of the pitch. Old folks summoned their dogs in vain when a refreshing dip proved irresistible; back on the riverbank, the dogs would shake rainbows of water off their fur. That’s the kind of day it was. The sun shone so brightly that the water sparkled like a shop window full of diamonds.

We were a bit late getting there. The best spots along the riverbank—where the water was shallow and perfect for a quick dip—were already gone. We carried on upriver until we found a spot where the grass hadn’t been flattened by too many towels. We spread out our rug. Father set up the barbecue and lit the coal. Mother sliced carrots and cucumbers. And I fell into the water. I’m hazy on the details now, but I remember the water being extremely cold and swallowing me up, and then the current sweeping me away. I have a memory of Mother’s voice shouting Father’s name, but that could also be my imagination. In any case, I saw Father jump fully clothed into the water and swim after me with powerful strokes. He made several attempts to grab hold of me before he eventually succeeded. He held me tight with one arm and slowly swam to the river bank with his free arm. Mother was in an awful state. She wrapped me up and rubbed me dry. As I sat there bundled in my towel, I looked up at Father, standing in the sun, soaking wet. I remember the water dripping from his clothes and beard, but the look in his eyes was very different that day. That day he was smiling.

It was a whole hour before Father came out of the bathroom. Hakim and Yasmin had left. I sat at the door, listening to the muffled sounds of the shower. Mother paced up and down the corridor. She had hastily knotted her woolly red cardigan round her waist. She kept running her hands through her hair. Eventually she told me to get up off the floor and go to my room. I pressed my ear to the bedroom wall but couldn’t hear a thing. I was scared and confused. I’d never seen Father this way, so frightened, so vulnerable. As if he’d used his last reserves to escape from some dark torture chamber, or been chased through the snow by ghosts he had barely managed to shake off. I wondered what kind of terrible news he must have got in that phone call to come home in such a state. My vivid imagination conjured up the worst for Grandmother in Lebanon. Maybe she’d told him she was very ill; maybe she’d said that this might be their last phone call. I imagined how sad this made Father, how he’d dropped the receiver, slumped to his knees, then staggered out of the telephone box and spent hours wandering aimlessly in the cold dark night.

As I stood there with my ear pressed to the wall, I realised I was shivering, covered in goose pimples. I wished it would all stop, that he’d come out of the bathroom, hug me and Mother, kiss our foreheads, and tell us that that was the end of his strange behaviour. I wished he’d come out and say sorry for hurting us again and again.

The bathroom door opened moments later. I heard Mother say something but couldn’t make it out. I resisted the urge to run out to them. I wanted him to come to my room. I wanted him to see how much he’d scared me, to sit down on my bed and talk to me, tell me what was wrong. I lay on my bed and stared at the door handle in the hope that he’d press it down and walk in. If he did, I’d quickly turn to face the wall so that he’d only see my back and would have to ask me how I was. But he never came. I heard two sets of footsteps heading for my parents’ bedroom, and Mother speaking again. She sounded very upset. Soon after that, I heard their door opening and Father coming out. Mother stayed behind.

This time I couldn’t resist. I darted out of my room and tugged him on the sleeve. He had changed into brown trousers and a check shirt, and smelled of shampoo and soap.

I whispered so that Mother wouldn’t hear. “Is Grandmother sick?”

He shook me off.

“Not now, Samir. Not just now …”

I wasn’t giving up. I tugged at his sleeve again.

“What happened to you?”

“Nothing, Samir. I had a fall. It was nothing serious.”

He took a few steps but I clung to his sleeve.

“But it looked serious.”

“Listen, habibi. Go back to your room, please. Get into bed.”

“But why?” I fought back tears of rage. I was sick of it, sick of trying to figure out what the point of his weird behaviour was. I wanted him to be himself again, immediately.

Father blinked nervously but his voice was calm and almost affectionate. “So that I can come to your room later and tell you the story.”

He was standing in a semi-circle of light, silhouetted by the hall light behind him.

“Abu Youssef?”

“Yes. The next episode is ready.”

He looked me in the eye, for the first time in ages. His gaze was unfathomable, alternating between sheer exhaustion and firm resolve.

“Can’t you tell me the story right now?”

“Later, Samir. There’s something I have to do first.”

“What?”

“I need to see Hakim. To tell him he needn’t worry and to apologise if I gave him a fright.”

I nodded. Hakim and Yasmin had been very puzzled leaving our flat. She’d held his hand and kept looking back at me. Still, I held on to my father’s sleeve and looked up at him.

“But you’ll come back, won’t you?”

He took a deep breath.

“Yes, Samir. I’ll only be down with Hakim for a few minutes, then I’ll come to your room.”

I let go of his sleeve.

“Can I come with you?”

“No. I won’t be long.”

“Promise?”

“I promise. You get yourself ready to hear the story. It’s about Abu Youssef’s treasure.”

“His big secret?”

“Yes, his big secret.”

He swallowed.

“Go to your room and wait for me. I’ll be back in no time.”

I did what I was told, and I heard our front door open and close.

This time, though, I had no intention of letting him go alone. I wasn’t going to let him out of my sight. I knew in my heart that he hadn’t really been chased in the dark by sinister characters. It was just my imagination playing tricks. But what if it wasn’t my imagination? Then they’d be out there waiting for him. They might have followed him all the way into our building and be lying in wait in a dim corner of the stairwell. And if they were hiding there, he’d need my help. I decided to follow him.

As soon as he was gone, I sneaked to the front door in my slippers. I opened it a crack and saw him disappear at the turn of the landing. I darted into the stairwell and stood with my back to the old wallpaper. I could still hear his footsteps and counted them as he descended. Too many steps—he had gone past Hakim and Yasmin’s door. That meant he’d lied to me. My heart was thumping so loudly I feared it would give me away. But there was no time to lose. I had to catch him before he got away from me. This time, I wanted to be by his side if anything happened. I peered round the corner to see if the coast was clear. Then I tiptoed down the stairs, following the creaks of his footsteps. My heart was racing and I hardly dared to breathe. For a second I was sure I’d lost him because the sound of his footsteps suddenly died. I was at the front door of our building now, at the bottom of the stairs, but the door was shut. That only left the stairs to the basement, but there was no light coming from there. I don’t think there even was a light down there. Suddenly I heard a sound, a bit like the squeal of wet brakes. I recognised it; I’d heard it a lot when we moved in. Father had opened the door to the basement.

It made me think of Yasmin, of the pair of us flitting around the haunted labyrinths in our old complex, following the strange smells that wafted through the walls. I wished she was by my side right now. She was far better at creeping up on people than I was. There was no way I could follow Father into the basement. The squealing door would give me away. He’d want to know why I followed him, why I didn’t trust him. He might decide to punish me by not telling me the story. It wasn’t worth the risk. Besides, I had no great desire to go down into the dark, dank basement where you could easily trip on the loose flagstones. Undecided, I looked around. Where should I go? Back upstairs until I heard him leaving the basement? But what if he slipped out the front door instead? I had no jacket; it would be crazy to follow him outside. Should I nip upstairs and get my jacket? But what if he left the basement in that space of time? What if Mother saw me and stopped me? What was he looking for anyway? As far as I knew, all we had in the basement were flattened-out removal boxes and a few smaller boxes storing stuff we didn’t need all year round, like Christmas-tree baubles, straw angels, and old crockery. I decided to wait, trusting that I’d be quick enough to react according to the situation. The light in the stairwell timed out, and I was left waiting in the dark.

It didn’t take too long. Ten minutes maybe. Ten minutes of sitting anxiously near the front door while my eyes got used to the dark. Then I heard the squeal again and Father closing the basement door behind him. This time I even heard the key turn and the lock click. I was already on my feet. The light came on again; he had pressed the switch. Once I heard him make his way upstairs again, I was certain that he wasn’t going to leave the house, that he’d come back to our flat. So I withdrew quickly and silently. This time Father did stop outside Hakim’s flat. I heard him knocking on the door. I peered cautiously round the corner. He was standing beneath the weak light bulb waiting for someone to open the door. In his two hands he clasped a rectangular object wrapped in black cloth. I couldn’t see his face because he was looking down at what he had in his hands. I hadn’t the faintest idea what was under that cloth. A gift to apologise to Hakim maybe? He knocked again. I heard steps and saw the door opening. Hakim was in his pyjamas, looking like a ragged seabird that’s come through a storm. The two men exchanged a long look without saying a word. Then Hakim nodded silently and stepped aside.

If you sit in one spot for a long time, you see things you never noticed before. You wonder how this can possibly be, since you’ve passed this spot a thousand times. I noticed for the first time the fine structure of the wallpaper in our stairwell. It was made up of lots of little joined-up diamonds that looked like they’d been embroidered. I’d never noticed the big grey dust balls in the corner of the staircase either. I took in every detail of my surroundings. Then the light went out. I didn’t dare turn it on again, so I started trying to identify animal shapes in the fine cracks in the wall—a squirrel, for example. But I grew bored once I realised I was only trying to distract myself. I stared at the outline of the door through which Father had disappeared. How I’d have loved to put my ear to it to hear what they were saying. Their muffled voices would have calmed me. But I couldn’t risk it. If Father found me here, he definitely wouldn’t tell me the story. And I had really earned it. I felt entitled to it. So I stayed put on the stairs, even though I’d much rather have been inside with Yasmin, under her warm duvet. I’d love to have been able to tell her she needn’t worry, that the whole thing with Father wasn’t so bad after all, and that I’d tell her the Abu Youssef story the next day. It would be very special because it was going to be about Abu Youssef’s secret treasure. I could already see her listening to me, throwing back her head and laughing at the funny bits. When she’d left our flat holding Hakim’s hand, her eyes had looked frightened and kind of sad too. She was probably wide awake in bed now, wondering what I was doing. The urge to sneak in to her was almost irresistible. But the door was closed. Yasmin was on the other side, and so was my father. There was no way I could go in.

Who knows how long I sat there. The silence was like a vacuum, an eternity. Eventually my eyelids grew heavy. I nodded off several times, waking up whenever my chin lolled onto my chest. I was neither asleep nor awake but drifting in half-sleep, until the murmur of voices filtered through. I woke with a start and opened my eyes wide. I clenched my fists and tensed my muscles, ready to sprint upstairs. I recognised Father’s voice, talking to Hakim. It was interrupted occasionally by what sounded like a short question; then Father’s voice again, firm and insistent. Eventually, the door opened a crack, though no one came out. Instead, I thought I heard a sob.

“Promise me,” I heard Father say, followed by louder sobs. The door opened a little wider. Now I could see the two of them. They held each other in a long embrace. Then Father took Hakim’s face between his hands, and his old friend looked at him with tearful eyes.

“Promise,” whispered Father.

Hakim nodded.

They looked at each other as if it was a staring contest. Then Father turned away. Hakim, tears creeping down the creases on his cheeks, hesitated on the threshold before closing the door. I saw Father rub his eyes, straighten his shirt, and press the light switch. He must have left whatever he’d been holding in Hakim’s flat. He looked up the stairs and took the first step, but by then I was well gone.

Back in my room, I stripped off my clothes and jumped into bed all out of breath. There was no sign of Mother. I could hear Father’s heavy steps, then the sound of the front door closing. I forced myself to breathe slowly. Father took his shoes off in the hall, then opened the door of my room enough to stick his head in.

“Samir?”

“Yes?”

“You OK?”

“Yes, I’m fine. Are things OK with Hakim again?”

“Yes. All sorted. Are you still awake? Do you still want the story?”

“Of course I do.”

Father smiled.

“OK. I’ll be with you shortly.”

He came back a few minutes later wearing pyjama bottoms and a soft sweater. I moved over so he could sit on the edge of my bed. I looked at him and tried to tell from his eyes whether he’d seen me out there, whether he knew that I’d followed him. There was no indication that he had.

“Why did it take so long?” I asked. When I saw him flinch, I added, “To finish the story?”

The light from my bedside lamp was reflected in his eyes.

“Good stories take time,” he said, “I had to do a lot of thinking about Abu Youssef.”

“So did I.”

“But now the wait is over.”

“About time too.”

“Are you sure you want to hear the story?”

“How do you mean?”

“Well …” He shrugged his shoulders and held out his hands, palms up. “I mean, maybe you’d rather keep it for another day?”

“Are you mad?”

“Once I’ve told it, the balance in the story account will be back to zero.”

“I don’t care.”

“Is that how you treat your piggybank as well?”

“Piggybanks don’t tell stories. Come on—please!”

Father pulled the duvet up around my shoulders and smiled.

“One day you’ll put your own children to bed and tell them stories.”

“You think?”

“Absolutely. It’s a wonderful thing, you know. You’ll spend lots of time thinking up stories, and your children will never forget them.”

I liked that idea. Me, Samir, a discoverer of imaginary worlds, a storyteller like my father. I lay on my side and tucked my hands under my pillow. I was ready. Right now, it no longer mattered that his behaviour had been so strange. Whatever it was that had made him so cold and distant, it didn’t matter anymore. He was here now. In my room, on my bed, with me. He had brought Abu Youssef along too. That was all that mattered.