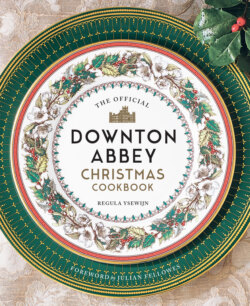

Читать книгу Official Downton Abbey Christmas Cookbook - Regula Ysewijn - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление|

17

Introduction

A SEASON OF FEASTING

AND FRIVOLTY

In medieval Catholic Britain, over half of the

days of the year were fast days, with all animal

products—meat, eggs, dairy—prohibited. By the

seventeenth century, the restrictions had been

reduced to the forty days of Lent, Fridays, and

many holy days. Anyone discovered defying the

rule was subject to a fine, which the rich gladly

paid. Fish was allowed, however, and its defini-

tion was surprisingly broad. It included beaver

tail, barnacle geese, and seals—in other words, if

it lived in or near the water, it was fish and there-

fore permitted. But despite the importance of

Christmas on the religious calendar,

meat was allowed on the holiday

table, and so Christmas turned into

the meat-focused feast still enjoyed

today. Indeed, Christmas appeared

to be more about feasting than it

was about the birth of Christ.

The Christmas season begin-

ning in December 1065 was an

eventful one,with the death of King

Edward (Edward the Confessor)

on January 4 and the crowning

of Harold II on January 6. Harold was the first

monarch to be crowned in Westminster Abbey,

which had been consecrated on December 28,

little more than a week earlier. By Christmas

1066, Harold was himself dead, with William I

(William the Conqueror) crowned the new king

on December 25. The following year, William

reportedly hosted a grand Christmas feast in

London to gain the favor of his subjects.

Some 350 years later, Richard II, who had

recently reopened the Parliament’s massive

Westminster Hall (which had been built under

William II in 1097) after ordering an expansion

and various embellishments to the original struc-

ture, hosted a Christmas feast in the hall that

boasted “twenty-eight oxen and three hundred

sheep, and game and fowls without number,feed-

ing ten thousand guests for many days.”The occa-

sion was accompanied by pageants and plays and

other entertainments typical of the time.

During the Christmas season of 1399, the

Earls of Huntington, Kent, and Salisbury, among

others, plotted to gain access to Windsor Castle

under the pretense of holiday guising, where

they hoped to capture Henry IV and restore the

deposed Richard II to the throne. Their planned

rebellion, which became known as the Epiphany

Rising, was thwarted by one of

their own betraying them to the

king, however, who promptly left

London. The conspirators, who

fled to the countryside, all met

a violent end. The imprisoned

Richard also never saw another

Christmas, though exactly how he

met his demise is unknown.

Encouraged by Henry VII,

Italian historian Polydore Vergil,

who spent most of his life in

England, wrote Anglia Historia, a history of

England, which he finished in 1513 but would

not be published for another two decades. In it

he notes that it was the custom of the English

as early as the reign of Henry II (1133 to 1189)

to celebrate Christmas with “plays, masques, and

magnificent spectacles, together with games as

dice and dancing, which . . . were not custom-

ary with other nations.” Vergil also mentions

the appointment of a Lord of Misrule, who was

chosen to oversee the entertainments, which, in

addition to organized events, typically included

wild partying and excessive amounts of drink.

Ssh. We’ll worry about

everything else later, but

for now, let’s just have a

very happy Christmas.

~ SEASON 5, EPISODE 9