Читать книгу Official Downton Abbey Christmas Cookbook - Regula Ysewijn - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление22

|

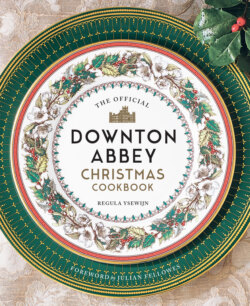

The Official Downton Abbey Christmas Cookbook

More and more people were working in facto-

ries and did not want to lose twelve days of pay,

as it would mean they may not be able to afford

food or their rent. But the upper classes also no

longer participated in the excessive, multiday

feasting common in the past, deeming it wild

and improper. The Christmas food tradition was

moving to the privacy of the home, where it was

a relatively quiet family celebration rather than a

rowdy public one.

In his comprehensive late eighteenth-century

book, Observations on Popular Antiquities, John

Brand writes of how a 1708 issue of the maga-

zine London Bewitched reported favorably on

the popularity of the season and of

the ingredient still associated with

Christmas today: “Grocers will now

begin to advance their plumbs, and

bellmen will be very studious con-

cerning their Christmas verses.”

Plumbs, or raisins, are the main

ingredient of Christmas fruitcake

and Christmas plum pudding, the

latter among the most adored and

most patriotic dishes of the century,

served with roast beef, another ele-

ment of national pride. The magazine then goes

on to report on the opposing Puritan side,though

the editors clearly don’t agree with it: “Fanaticks

will begin to preach down superstitious minc’d

pyes and abominable plumb porridge; and the

Church of England will highly stand up for the

old Christmas hospitality.”

HOLIDAY TRADITIONS,

OLD AND NEW

In the nineteenth century, the British began look-

ing to the past for lost Christmas traditions that

could be revived in the present.This nostalgia for

the old ways produced many of the Christmas

customs seen in the Downton era and still prac-

ticed today. Christmas carols, lost when the rule

of Cromwell forbade them, were brought back to

life, and new books of carols appeared. Thomas

Hervey’s The Book of Christmas, published in

1836 and illustrated by Robert Seymour, one of

the most successful caricaturists of the era, gives

a comprehensive account of English Christmas

customs in the early nineteenth century. In it the

reader sees illustrations of a Christmas still recog-

nizable today, with holly sprig–decorated plum

pudding together with roast beef at the center of

the holiday table, mince pies, enormous racks of

beef bought and sold in the streets, and a carriage

full of turkeys.

Christmas literature as a new

discipline became popular in the

Victorian period, finding its roots

in Shakespeare’s seventeenth-

century The Winter’s Tale and

in the early nineteenth-century

ghost stories of Lord Byron, Mary

Shelley, and John Polidori. Fright-

ening people around Christmas-

time drew on the scary guises of

mummers in the past. In 1835,

Charles Dickens published “Christmas Festivi-

ties,” his first essay about Christmas, in a London

weekly newspaper. In it he explains how Christ-

mas should be enjoyed as both a time of reflection

and a family occasion: “A Christmas family party!

We know nothing in nature more delightful!” In

the same essay, he breathes new life into a for-

gotten custom that was, according to contempo-

rary historian Mark Forsyth, popular in England

between 1720 and 1784: kissing under the mistle-

toe. In those days, a berry had to be picked from

the mistletoe sprig before each kiss.

By December 1843, when A Christmas Carol

was published, the revival of Christmas was in full

Well, if you’re going

to be miserable, you

might as well do it in

charming surroundings.

~ SEASON 5, EPISODE 9