Читать книгу Official Downton Abbey Christmas Cookbook - Regula Ysewijn - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление20

|

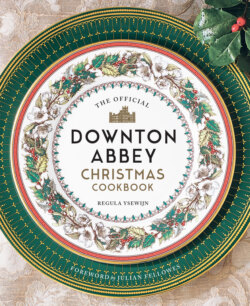

The Official Downton Abbey Christmas Cookbook

Christmas, or Good Friday, firmly linking these

prized sweets to religious events.

The Reformation lead to the rise of Puritanism,

and in the seventeenth century, the increasing dis-

like for any Catholic customs. Puritans claimed

Charles I, who had married the Catholic daugh-

ter of Henry IV of France, had too much affinity

with her faith and feared he would weaken the

official establishment of the reformed Church of

England. In 1644, an act of Parliament banned

the celebration of Christmas. It stipulated that

the feast should be abolished, and that the sins

of our forefathers should be remembered for

they “turned this Feast, pretending the Memory

of Christ, into an extreme Forgetfulness of him,

by giving Liberty to carnal and sensual Delights,

being contrary to the Life which Christ led here

on Earth. . . .”In other words, the celebrants were

having way too much fun on Christmas. Three

years later, in 1647, an ordinance was passed that

reiterated the abolishment of the feast.

England became a republic under Oliver

Cromwell, who ruled England, Scotland, and

Ireland from 1653 until his death just five years

later. Cromwell made his dislike for any form of

feasting clear, discarding it as mere popery. If only

Henry VIII could have known that his ending of

the authority of the Roman Catholic Church over

the Church of England would lead to the abolish-

ment of his favorite festival.But this does not mean

that people didn’t continue to celebrate Christmas

in secret: During Christmas 1652, the great mem-

oirist John Evelyn mentions in his diary, rather

disgruntledly, “Christmas day, no sermon any-

where, no church being permitted to be open, so

observed it at home.”Three years later, he remarks

that no notice of Christmas Day was taken, but in

1657, he goes to hear a secret sermon in London’s

Exeter Chapel, which is soon surrounded by sol-

diers. Evelyn is questioned as to “why, contrary to

the ordinance made that none should any longer

observe the superstitious times of the Nativity,”

he is praying on Christmas. He is dismayed to

be disturbed in trying to pray for Christ and for

Charles II, who is in exile, but he accepts that he

got off fairly easily given that the soldiers threat-

ened all the worshippers with muskets.

The year 1660 marked both the return of

Charles II to the throne and the first legal cel-

ebration of Christmas since 1644. Charles was

nicknamed The Merry Monarch because he used

any excuse to throw a big, extravagant party.

Outside of the court, Christmas was making a

comeback more slowly, as is evident in the rather

modest festivities described by England’s favorite

seventeenth-century diarist, Samuel Pepys. On

December 24, he mentions making the house

ready “to-morrow being Christmas day.” On

December 25, he goes to church in the morning,

then has dinner (at that time, a midday meal)

with his wife and his brother, feasting on mut-

ton and a chicken. After dinner, he goes to church

again, and that’s about it for Christmas cheer.The

custom of the Christmas box, which has its roots

in the alms boxes of the Middle Ages, also returns

with the monarchy.On December 19,1663,Pepys

describes going to pay his shoemaker and giving

“something to the boys’ box against Christmas.”

Recipe collections of the period do not men-

tion Christmas, though mince pies, fruitcakes, and

plum pudding do appear in them in great numbers.

By the eighteenth century, the endless feasting

associated with the Twelve Days of Christmas had

begun to disappear. Henry Bourne’s Antiquitates

Vulgares: Or the Antiquities of the Common People,

published in 1725, chronicled the old traditions

of Christmas and had little positive to say about

them. Bourne compared the custom of caroling to

rioting and deemed mumming and gift giving on

New Year’s superstitious and sinful.