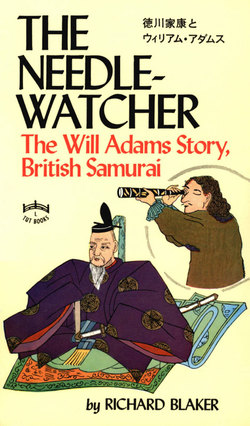

Читать книгу Needle-Watcher - Richard Blaker - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER III

AT Sakai they landed, and took the road again. After ten miles of it, when their bowels, despite the steadiness of their gazing eyes, faintly shook at the message from the crosses, they thought again of the padre. His talk, they saw, had not been empty when he had talked of death for Pirates and Robbers and Enemies to the Majesty of Japan. Death, which was that whole rotting avenue, was wide enough to embrace more than the malefactors specified by the priest. It was wide enough to embrace just and unjust alike; wide as storm or pestilence. They were nauseated, but not afraid; and this simply because fear was a thing forgotten. They saw the odds and accepted them. Besides this, their minds were static, numbed by the immense fact that of a whole world they had come to the end.

Of the city of Osaka Captain John Saris had a good deal to say thirteen years later; but Saris, so far from being at the dead end of any world, was at the well-omened beginning of a new one. There was a caparisoned horse at his disposal, a halberdier by way of personal body-guard. There was, too, another Englishman with him who made of his journey a great matter, an affair of comfort and of consequence.

"We found Osaka," says this Saris, "to be a very great Towne, as great as London within the walls, with many faire Timber bridges of a great height, serving to passe ower a river there as wide as the Thames at London . . . hauing a castle in it, maruellous large and strong, with very deepe trenches about it, with many drawe bridges, with gates plated with iron. The Castle is built all off Freestone, with Bulwarks and Battlements, with loop-holes for small shot and arrows, and divers passages to cast stones upon the assaylants. The walls are at the least sixe or seven yards thicke . . ."

It was through a postern in the inmost of these same walls that Adams and Santvoort were carried to an outhouse in the castle yard. Within minutes they were at ease, reclining in a great tub of hot water. The bulky pocket-compass that had spent some years in Adams' breeches-pocket was now on a cord around his neck. At a small tub a few yards from them their shirts and breeches were being scrubbed and whacked.

The warm water, the cool shade of afternoon, the fact that nimbly living men again outnumbered corpses and gobbets of flesh adhering to crosses reduced the two to the frame of mind wherein curious ceremonial is accepted as normal routine.

From the bath they went to mats whereon blind men gently pounded and kneaded and massaged their spent muscles. Other men with sharply shining blades in their hands approached them. They did not cut their throats, but clipped their hair and shaved their faces. Others again gave them millet-broth and rice. Thereafter they lay upon the mats, with roughly-woven coverlets, and slept.

At twilight they were roused and before them were their dried shirts and breeches. The scouring at the tub had brought back some of the old lustre to codpieces that had flaunted, in another world, virility. Straw sandals had been plaited for them that were not a jest, but fitted their feet.

Bare-shanked—for hose were things of the past—and bareheaded, for it was now evening, they walked among soldiers towards "the great King of the land."

The court, Adams himself noticed at the time, was "a wonderful costly house, gilded with gold in aboundance." He had learned from the soldiers, the boatmen and the bearers the name by which he was known; so that when someone in the chamber said "An-jin" he stood forward in the Presence.

Before him, in the light of suspended lanterns, on a low cushioned divan, sat Tokugawa Ieyasu. Adams saw him first as a robe of simple magnificence draped upon a lithe body, hands folded upon feet in white socks below two long sword-hilts. The head was shaved, to make of the face a smooth mask that extended from the chin to the extreme top of the cranium. The lips were parted in a faint smile—not the smile of the whole nation that clicked and twinkled upon every passing triviality, but the smile of a sage that hovered, immobile, about the contemplation of a dream. The eyes looked out upon Adams with the nation's alert interest in whatever new thing was brought before them, but behind this bright glint was a shadow also; and the shadow swallowed into its unfathomable depths whatever lively image the glint and sparkle brought to it.

Soldier to the extent of nimble wrestler and swordsman-acrobat; philosopher, statesman, economist and dreamer; man of no fear, no mercy, no hate—leyasu, sitting on his low divan in the lantern-light, had troubles enough of his own as he looked out, through the depths of his dream, upon his latest prisoners.

What he saw was a large, cumbersome frame in a newly-patched, newly-washed shirt and coarse, threadbare breeches. It was not poised lightly and easily as the bodies to which his sight was accustomed, but was planted clumsily over slightly splayed, prodigiously hairy shanks and wide feet. Forearms, again prodigiously hairy, were folded across the chest, and above them, between the flaps of the open shirt, in a tangle of brown hair like the pelt of a young fox, hung the execrable workmanship in ebony and tortoise-shell, of Adams' compass-case. Youth had been restored to the pilot's face by the meticulous shaving of it, and by the clipping that had set the hair standing upright on his head. He appeared, in the soft light of the lanterns, instead of a battered and spent seaman of thirty-six, more like a sick young man of twenty-five or thirty.

The eyes of the two met and for a few moments were engaged in scrutiny. Adams looked into eyes that saw more than any other two eyes in that, or perhaps any, country. And they, in their turn, looked upon and recognised—a possibility.

"An-jin . . ." The Shogun mused aloud.

Adams had no thought wherewith to answer the thoughtful summons, if summons it was. Instead of thought he made a gesture. He slipped the cord necklace over his head, stepped forward and held it out with the clumsy pendant compass, to leyasu.

The Shogun took it from him.

Adams stepped back, stripped of his last possession—for his shirt and his breeches were no more a worldly possession than the skin on his back or the hair on his chest.

The gesture may have been a happy fluke that counted for much by virtue of its symbolic value. It was a gift, given with obvious freedom and spontaneity; it was useless enough to Adams now between walls of freestone six or seven yards thick with an avenue of corpses beyond. It was the only articulate answer he had to the speaking of his name—Pilot. leyasu spoke to one who stood beside him. The man left them and returned immediately with a silk coat which he held, for Adams to thrust his arms into the loose sleeves. A second coat was handed by the bearer to Santvoort where he stood behind Adams.

So far none but the Shogun had spoken, so that speech seemed to be a thing of the past and neither Adams nor Santvoort uttered either thanks or comment.

From their dull and despondent apathy this movement and pantomime braced them into a moment of suspense. But the faces about them were impassive as ever. Impassive was leyasu with his smile; impassive the guards at the door; impassive the coat-bringer, impassive the man who had sat or stood within sword's thrust of them for every moment that they had been within the walls. Nothing, from the impassivity of them all, was likely to happen. And nothing did happen.

A nod from the Shogun on his divan produced a movement and a beckoning from their attendant. Adams and Santvoort turned, in their new coats, to follow him out. Before they went, however, the eye of Adams again met the eye of leyasu.

In their outhouse they sat and talked, while within a yard of them was their attendant, nimble as a leopard and still as an image. His presence was the presence of two swords girded to a power like the power lurking in a cloud that can split the stillness of the sky with a blade of lightning.

They talked though there was still nothing, or next to nothing, that they could say.

Adams mentioned the rich gilding of the audience chamber, the bronze and silver-work of the lanterns. They examined their coats. Adams's was the better one. They agreed that there was a general friendliness in the atmosphere; that the things on and about the crosses had been, probably, only scamps and utter rascals. They had seen no skin that was white in all the festering garbage. They wished to God that they could have spoken in the gibberish of Japan; or they wished again that someone could have come to them through the doorway of their good Dutch or indifferent Portuguese or Spanish—someone other than the sinister padre.

"Perhaps he will come," Santvoort suggested.

"Perhaps," said Adams.

"We might kill him," was the Dutchman's next suggestion.

They looked at their attendant—hands tucked into voluminous sleeves half a dozen inches from sword-hilts.

"Perhaps," said Adams.

A menial brought them food again; broth and rice and shreds of fish. They ate and then slept.

When they awoke in the morning, before they had exchanged a word, a man raised himself from squatting and went out. His place was immediately taken by their regular escort. He accompanied them to the bath and sat beside them afterwards while they sunned themselves. Even their very fair sense of well-being after their weeks of malaise scarcely opened up talk between them. If they had known anything at all they could have talked equally whether their knowledge had been of doom, or of harmlessness, or of a dog's chance between the two. But they knew nothing—except, possibly, that all the others knew something which they could not tell; the Emperor and the silent, wakeful men about him and the inscrutable escort who never left them while they woke.

Speculation could lead them nowhere.

"You would not think," Adams ventured, "that they would give us handsome coats to kill us in."

Santvoort shrugged his Dutch shoulders. "You would not think," he said, "that a man would shake hands with himself in greeting of another. Yet these men do it."

"In a latitude of thirty," Adams said later, "it would be hotter than this."

"In the latitude of hell," said Santvoort, "it would be hotter still."

The thought led no further.

"The coats, Melchior," said Adams. "The coats are a good sign."

When they had eaten breakfast their escort rose and indicated their sandals, and beckoned them towards the courtyard again. His sign towards their coats, lying on their mats, may have been meant to inform them only that they were going again to the presence whence the coats had come. Adams, however, said: "Aye; we'll wear our coats."

They were dizzied for some moments in the soft light of the chamber. They made clumsy obeisance in the direction of the divan before they exclaimed aloud, "God's body!" and "Hell's damnation!" and stopped in their breathing; for beside the divan, with his thumbs stuck in his girdle, his head and shoulders peculiarly contracted in sly humility, was the Nagasaki priest.

He, too, for a moment was shaken. He saw young men shaved and clipped and kempt and natty in silk jackets where he had expected ragged castaways.

The padre's smile was not as the smile of the others. His eyes shifted and shot from Adams to Santvoort and the guards and attendants, and slid, sidelong, to leyasu.

The Shogun did not give him so much as a glance.

As though reading the pages of a deep and difficult book he kept the focus of his eyes and of his smile on Adams. When he had read the riddle upon the page, or the answer to the riddle in his mind, he nodded.

The priest's shoulders bowed still more narrowly. His tongue played over his teeth to moisten the lips.

"Englishman and Hollander," he said, speaking slowly and portentously in his excellent Dutch, "the Lord Generalissimo's Majesty charges you with piracy, robbery and murder upon his seas. You are conspirators against his Dominion. You seek to bring war into his peace."

It was still not at the priest that leyasu looked. He glanced once at Santvoort, once at their particular escort; and then rested his gaze on Adams.

"Liar!" Santvoort snorted. And then, "Will, for God's love-"

Adams began to speak.

He started in Dutch, laboriously and thoughtfully at first, and fairly calmly.

There was strict piety and no savour at all of profanity when he asserted, by God's Body and His Blood, that the padre lied and that he knew he lied. A copy of the Rotterdam Company's indenture with him, and its Articles, was in the ship's book for any man to see that the intent of the voyage was peaceful trade. The cargezon and the bills of lading would show that there was not an article on board that had not been lawfully bought and peaceably loaded before the anchor had been weighed. If they were murderers and pirates, where were the witnesses to their murder and their piracy?

"Witnesses!" said the priest. "Good." He licked his lips again. "His Majesty has his witnesses."

Bowing, he clicked out some sounds and leyasu nodded.

"They have confessed all. Both of them." While the priest said this, two men were brought in, pale and travel-worn, still wide-eyed and a-tremble with their fever, ragged and haggard.

Adams and the Dutchman stared at them aghast; for they had left these same men, restless and scratching and mumbling on their mats, in the house at Oita.

"Master Gilbert de Conning," the priest said, "has made and signed a deposition. He is chief merchant of your ship."

"Chief merchant my—" said Adams. "He is a Huguenot, and a whoreson cook."

"Chief merchant," insisted the priest, "merchant of the goods you bought; receiver of the goods you stole. He has confessed and firmed his confession in writing. Witness thereto is Jan Abelson van Owater." The second man slunk a little forward.

"Bastards both," snorted Adams, and the chamber spun about him.

The Dutch language was shrunk too small and too thin for any further use. His mind flung away from it to the mother language spoken by that other William of his age, more famous than himself. Most of the lively, robustious words that have been cut, from time to time, out of the works of Shakespeare, tumbled over each other upon ears that understood them not but felt only the heat of the explosion that shot them forth. Other words came too, that would probably have been new and vastly interesting to Shakespeare himself—words peculiar to docks and wharves and bawdy-houses of the riverside; and words used only in the fo'c'stle of ships labouring at sea.

Santvoort recognised some of these and they gave him the spirit of the Pilot's discourse. In the specialised remarks of any Dutch seaman who had sailed with Spaniards, he added anything that Adams might have missed in his homely English.

Adams was still convalescent and the outburst left him pumped, and a little exhausted. It left him, too, with a sudden feeling of flat futility. The turbulence of speech in live words had given an illusion of the old, familiar world again wherein effort brought, sometimes, its result; where strife, sometimes, brought victory to the strivers. But the illusion was suddenly gone. Words, here, were meaningless and forceless, like water squirted over statues. Effort was a fantastic memory for naked men among men clad in swords.

The two renegades, de Conning the cook, and Owater whom Santvoort had cuffed a dozen times over the head, grinned in calm discomfort at each other. Thought of strife was thought of suicide. Adams shrugged his shoulders and abandoned it. leyasu himself was seen to have been studying this outburst —for was not the conduct of men but writing on the page of Life?

He straightened a little on his divan and spoke.

Adams and Santvoort were led back to their outhouse, where they lay down upon their mats and found, at their leisure, new words and new combinations of words to apply to the priest and to Conning and van Owater.

Their escort sat by the door, deaf as ever and dumb, filled with his own distant thoughts.