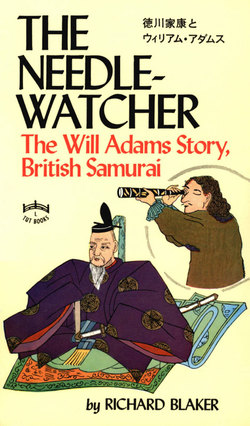

Читать книгу Needle-Watcher - Richard Blaker - Страница 20

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER XI

HE cheerily shouted his farewell to them when he had scrambled down from the port into his skiff, smiling and waving his great hat, then making the sign of the cross. They called back from the deck waving their hands in ostentatious friendliness, mindful of the soldiers who stood at the rail above them, watching.

Santvoort went back with the captain and the surgeon to the cuddy; Adams took his straw hat from its peg by the cuddy door and went up on the poop. He looked, casually, for Mitsu, but did not see him.

Wherever he looked he saw a detail of the ship's familiar helplessness. The hole in the deck at his feet had only the bent pin of the pivot sticking out, rusty, from its iron collar; for the steering whip-staff—a comely and handy and detachable piece of timber—had gone the way of other comely, handy and detachable things. He sat on a water-breaker from which one hoop had gone and which, until a cooper had spent half a day upon it, could hold not a pint of water; and he stared at the binnacle.

There was irony in his thoughtful gaze, for he—An-jin as they called him, Contemplator of the Needle—now contemplated only an emptiness where there was no needle. The card had gone, and the binnacle might have been another leaky keg for all the use it was.

The pitch oozed out of seams and wriggled into blisters even as he watched it.

The broad, hunched shoulders of the padre rose and lurched as the skiff was grounded. He stepped out of it, gathering up the skirts of his cassock into the hands that fumbled also with destinies.

He had explained himself. Even Adams believed that he had told the utmost truth; but in believing him he distrusted him the more. The explanation was Popery. . . . And at that point the mind of Adams stuck.

Before going down to the others in the cuddy he looked once more for Mitsu, but still did not see him.

"A pistol and a knife," the captain was saying—"All very well; but it would require more than a pistol and a knife for the sinking of a Spaniard, if matters came to it."

"Nevertheless," said Santvoort, "a pistol and a knife would be more comfortable than no pistol and no knife."

They discussed it all in the sombre, considerate manner of directors of an insolvent company. There was no emotion in their talk, just the consideration of liabilities, speculation as to assets. Assets resolved themselves into the promised knife and pistol. The thought of meat again—regular or even occasional meat—may have played some part in their estimates. Also they may have had thoughts of drink that was not brewed from rice; but whatever thoughts they may have had, their words were of the pistol and the knife.

"And, Will?" said Santvoort, "what does Will say?"

"Yes," said the surgeon. "What does Mr. Adams say?" For Adams had so far said nothing.

"What I say," said Adams, "is that he can fill his pistol with balls and swallow it, and sit on his knife. To hell with him."

They laughed first; and then they stared at Adams.

Adams was, in a sense, staring at himself; for he had not realised, till then, that his decision was so vehement, or indeed that he had come to a decision at all.

"Do you not want a pistol and a knife, then?" asked the captain.

"I want them well enough," said Adams. "And there is nothing I can see to prevent our having them. If they come in the boat we can take them. But as for going with the dog, that is another story."

"Do you think he still lies?" asked Santvoort. Their minds were still open on that point and Adams, after his vehemence, surprised them by saying, quietly, "No."

"Then, if he is honest-" one of them began; but Adams interrupted him; "Even if he is honest he is—he is—" he hesitated and stumbled for some word that would make clear to them the thought that was dim in his own mind. "He is himself."

That was the best he could do with it, for his decision had come from a process too simple for discussions or explanations. He had considered Ieyasu who had called him "An-jin" and the priest who had called him "son." As the result of the two considerations his decision was already made. He could not have explained it any more than certain other men could have explained their choice when they dropped the business of net-mending and followed after the stranger who had said to them, "Follow me."

"You go," he said, "if go you must. I will stay. The odds are against your getting home—but there is a chance that you may do it that way."

"Do you not want to go, then?" It was Santvoort who actually asked the question though something in the manner of Adams's speaking had brought it uppermost into the minds of all three.

"Well enough," said Adams. "I suppose I do want to go, as you do. But-"

"Four would have a better chance than three," the surgeon suggested.

Adams shrugged his shoulders. "That," he said, "no man can say. The contrary may be the truth. It is all a hazard. Perhaps my staying here would make your going safer, since I know the Portingal's share in it, and could perhaps hold him to his bargain. But that is as it may be. Go. I stay."

"Who said we were going?" demanded Santvoort. "If it is not good enough for you, Will, it is not good enough for me. I stay too."

"We have by no means decided," said the captain. "There is still much to be said on both sides. But if Santvoort and you are already resolved—well, it is all one to me."

"And to me," said the surgeon. "For, when in doubt do nothing, is the soundest wisdom that I have ever learned."

"Doubt," said Adams. "I am in no doubt. I will follow no man who lies and schemes counter to the Emperor. He would have crossed us, but the Emperor spared us."

They drank another round of the wine the padre had brought them, and another to empty the second bottle.

They began to see their rejection of the offer in the light of an adventure, and talked of it brightly.

"In doubt do nothing, according to the surgeon," Adams said, "but there is much we can, and will do. We will discover the whole plot to Mitsu and his men." Santvoort opened the third bottle. He filled the mugs, and Adams went on. "Let the boat come; Mitsu and others will board it instead of us. The pistols and knives will prove it—and the carrying of arms is itself a powerful offence."

They grew loud in their talk after their months of perplexed silence.

Adams was as lusty as the best of them. "We'll show them!" he shouted. "The Emperor shall see who are his prowling enemies, and who his friends. Drink to him, lads!" They raised their mugs and stood absurdly ceremonious with their shoulders bent under the cuddy ceiling, steadying themselves with a hand on the table.

"The Emperor!" Adams gave them the toast, pompous enough for a Lord Mayor's banquet. "leyasu! our friend!"

The others mumbled after him, "The Emperor," and bent their knees to straighten their throats to the heel-taps in their mugs.

It was the drink that had brought lustiness and final lucidity to the words of Adams. It was assisted, possibly, by his luck.

For at a knot-hole in the planking of the cuddy's dim ceiling was the flat, neat little ear of Mitsu, where it had been for three hours.

For three hours the swordsman who was also acrobat and the trustiest of Ieyasu's secret service men had been stewing in his sweat between the timbers of the poop deck and the planks of the cuddy ceiling. He had not spent ten minutes on the ship before finding that the removal of a small locker-side above the tiller would give him a place where an eye and an ear placed alternately at the knot-hole would tell him much that his Lord would be interested to know.